On March 4, 2025, the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments in Mexico’s lawsuit against Smith & Wesson, which seeks to hold U.S. gun makers accountable for gun-related crime in Mexico. This part of the case isn’t to hear the merits or evidence. It’s to determine if the case can even be brought under the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act (PLCCA).

In its 2021 lawsuit, styled as Smith & Wesson Brands v. Estados Unidos Mexicanos on appeal to the Supreme Court, the Mexican government accused Smith & Wesson, Colt and other U.S. gunmakers of knowingly selling guns to a small set of Federal Firearms License dealers who break American law and sell guns to straw purchasers and other illicit buyers, to the tune of 2 percent of U.S. production.

The straw purchasers then somehow arrange to deliver the firearms to criminals in Mexico, in particular, drug cartel members.

Noel Francisco, lawyer for the plaintiffs Smith & Wesson Brands, Inc. and others who petitioned the case to the Supreme Court, “If Mexico is right, then every law enforcement organization in America has missed the largest criminal conspiracy in history operating right under their nose, and Budweiser is liable for every accident caused by underage drinkers since it knows that teenagers will buy beer, drive drunk and crash.”

Lawyers for the gunmakers say the federal immunity law, PLCCA, with the acronym pronounced “Plikka” or “Plakka,” protects the companies from liability that results from “criminal or unlawful misuse” of a firearm by a third party.

To get around PLCCA’s protections, Mexico’s legal team honed in on a narrow “predicate” exception to PLCCA liability that allow a gun manufacturer to be sued. PLCCA was a bipartisan measure passed to protect gun companies from being sued by anti-gun cities and states and gun-control organizations with the intent of bankrupting the gun companies with legal fees.

Mexico’s lawsuit cannot fit in the exceptions, the companies say, because its arguments for liability rely on linking a long chain of independent third parties, including the gun dealers and traffickers, to the defendant companies.

The district court ruled in favor of the manufacturers and Mexico appealed. The Boston-based 1st U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals agreed that while the protections of PLCAA were applicable to the manufacturers, they might still be liable under the predicate exception.

Francisco, a former solicitor general of the United States, said that Mexico’s “theory is that federally licensed manufacturers sell firearms to licensed distributors, who sell to licensed retailers, a small percentage of whom sell to straw purchasers, some of whom transfer to smugglers, who then smuggle them into Mexico, hand them over to cartels, who in turn use them to commit murder and mayhem, all of which requires the government of Mexico to spend money.

“Needless to say, no case in American history supports that theory, and it’s squarely foreclosed by the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act.”

In one exchange that highlights the irony of the Mexican government’s suit reaching the Supreme Court, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson pressed the Mexican government’s attorney, Catherine Stetson, about whether PLCAA was intended to bar lawsuits like Mexico’s.

“I worry that we’re running up against the very concerns that motivated this statute to begin with,” Jackson said during the oral arguments. “All of the things that you ask for in this lawsuit would amount to different kinds of regulatory constraints that I’m thinking Congress didn’t want the courts to be the ones to impose.”

After reviewing oral arguments, Hannah Hill, vice president of the National Foundation for Gun Rights, said, “The one thing that was clear from today’s oral arguments is that Mexico does not have a leg to stand on. Their arguments that gun manufacturers are to blame for the downstream actions of independent third parties is laughable, and that was made abundantly clear to the Justices. We are hopeful for a ruling that says just that.”

“What you don’t have is particular dealers, right?” Justice Elena Kagan asked Mexico’s lawyer Stetson, in relation to the specific allegations in the lawsuit. “Who are they aiding and abetting in this complaint?”

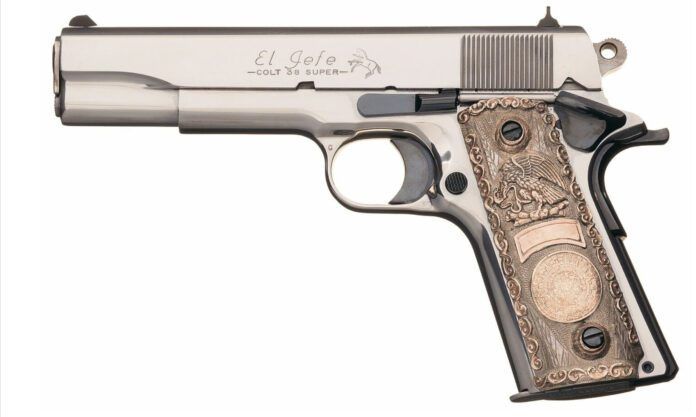

Amusingly, Mexico also alleged in the lawsuit that the companies design certain weapons that appeal to cartel members, including Colt handguns known as the Super El Jefe (the boss), the Super El Grito (name of the ceremony that commemorates the beginning of the Mexican War of Independence in 1810), and the Emiliano Zapata 1911. Likely, the “Super” nomenclature is related to the chamberings on those pistols, which fire 38 Super rounds.

Chief Justice John Roberts said, “Those are all things that are not illegal in any way. There are some people who want the experience of shooting a particular type of gun because they find it more enjoyable than using a BB gun,” he added.

For your listening and reading pleasure, the oral arguments are attached to this blog as an MP3 audio file and as a PDF. Gun Tests recommends listening to the MP3 file while scrolling the PDF document to understand the terms and complex case law mentioned in the oral arguments. It takes about 90 minutes if you don’t stop to often to rehear certain sentences.

Click here to listen to the audio file or click below to start the sound.

Click here to download the oral argument PDF.

IF THIS HOLDS UP FOR MEXICO, THEN EVERY FAMILY MEMBER OF A PERSON KILLED IN A WAR IN THE WORLD CAN SUE FOR DAMAGES.

What about the atf under the Clinton admin? When they> {Eric Holder?} shipped a fer thousand gund to Mexico!