Up for testing this month are three 45-70 lever-action rifles. Two, by Marlin and Henry, are made in the U.S. and are fairly handy carbine-length firearms. The third is a huge, heavy, octagonal-barrel copy of the original 1886 Winchester, bearing Winchester’s name but made by Miroku in Japan. The Henry and Marlin have dull finishes. The Marlin is matte stainless steel and the Henry, blued steel. The Winchester has a glossy blued finish that we thought was superb. The two carbines have appropriately padded buttstocks, but the classy-looking Winchester has a hook-shaped buttplate of steel, entirely appropriate for the era and for the weight of the gun. There were some design differences we thought were mighty interesting, including an unusual safety system on the Henry, and three different types of iron sights. We tested them using their iron sights with Remington 405-grain soft points and with Winchester 300-grain jacketed hollowpoint ammo. Here is what we found.

Marlin Model 1895GS 45-70 Government, $837

We noted that Marlin does not call this the Guide Gun on the company website. That name is used only on the blued version. This matte-finished stainless-steel rifle had light-blond walnut butt and forend wood, very well checkered and fitted tightly to the action and the barrel. Each checkered wrist panel and the wrap-around forend checkering had an attractive diamond shape of uncheckered wood, a classy touch. The 18.5-inch barrel had a superb crown, and was fitted with blued iron sights that were a large gold dot front with provisions for a (missing) hood, and a “semi-buckhorn” wide-angle, U-shaped rear with a small U in the middle. The rear sight folds out of the way if you want to put a scope on it. The receivers of both the Marlin and Henry are drilled and tapped for easy scope mounting, never mind that a scope would take away much of the handy, uncluttered convenience of these two rifles. There were no provisions on the Marlin for our first choice of rear sight, which is an adjustable aperture. Instead of the semi-buckhorn of the Marlin, we’d have been happier with a wide-angle V with no secondary notch and with a center line, but U.S. manufacturers seem to have great reluctance to use express sights. With the setup as it is, there is always a question about how much of the front bead should be stuck up above the rear notch. With a proper express sight, there is never such a question. The rifle was supplied to us by a dealer and arrived with the hood missing. The missing front hood did not help us get a good sight picture. The light caused the front sight to shine and blend with the target color. Hoods are there for a reason.

We found entirely too much information stamped into the barrel. The Marlin name, address, and caliber designations are fine, but to imprint a statement on the barrel that basically says, “This is a gun and it’s dangerous” is a bit silly. The fit and finish of all the metalwork was just fine, we thought. The lever worked smoothly, and the rifle had an excellent trigger pull. The rifle was handy, relatively light at 6.8 pounds unloaded (lightest of the three test rifles), and good looking. The wood finish left a bit to be desired. It had open grain, which would probably take linseed oil quite well, and that would darken the stock, which might make the rifle all the more attractive. So maybe we ought not to complain. The direction of the wood grain in the forend and buttstock were excellent. This looked to be a very durable stock, though it was decidedly on the plain side. The trestle-style buttpad was a good one, soft and springy.

We found another feature on the Marlin we thought was a good idea. It was fitted with a cross-pin safety just in front of the hammer. Work the lever and chamber a round, and the hammer is then at full cock. But if you don’t want to shoot immediately, you need to lower the hammer to half cock. It’s non-rebounding, so there’s a half-cock position. By first putting on that cross-pin safety, you can easily lower the hammer with complete safety. Without that cross-pin safety, on a cold day your thumb might slip, and that could fire the rifle. So the procedure is to put the safety on, chamber a round, lower the hammer carefully to the half-cock position, and then take the safety off. That way all you have to do is cock the rifle when you’re ready to shoot.

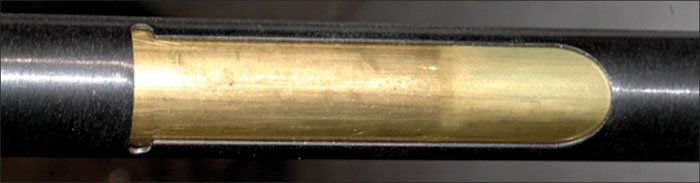

Loading the rifle was accomplished by shoving each round against a spring into the right side of the receiver, and that was easy enough. The rifle held 4+1 rounds. The cut-rifled barrel looked just great inside. We though it would shoot very well, and as it turned out, we were not disappointed.

Our first two shots were with some of the Buffalo Bore 45-70 Magnum loads, which aren’t featured in this report, but we wanted to see how brutal this light rifle might be with those loads. The Buffalo Bore loads we tried featured a 350-grain flat-nose jacketed bullet at about 2150 fps. One shot got us a severe clout on our nose, and a second shot cut our lip nicely. We called it good enough. If you want those stomping rounds in your gun, which is an excellent idea in bear country, you might want to lengthen the pull just a touch. One of the slip-on recoil pads would do that easily, and also be kinder to your shoulder.

With our test ammo the rifle shot groups of 1.3 inches with the Remington and 4.8 with the Winchester at 50 yards. As noted, the front sight tended to disappear against the target. We believe the rifle will do better than that, but our testing was enough to indicate a strong preference for the heavier bullets of the Remington loads. We had to tap the rear sight about an eighth of an inch to the left to get it centered. The Remington ammo hit slightly high and the Winchester hit slightly low.

Our Team Said: We liked this little rifle quite a bit. The action was slick, and it fed and ejected positively every time. But the trigger was too heavy, and we’d prefer a better rear sight.

Henry Repeating ArmsLever Action Rifle H01045-70 Government, $850

This matte-blued rifle had dark wood, which was in keeping with the overall dark look, just as the Marlin had a lighter overall look. The checkering was excellent, with three panels on the squarish forend and one on each side of the pistol grip. The checkering panels were decorated with curved lines, all in all an attractive job. The wood-to-metal fit was excellent, maybe better than Marlin’s, but certainly no worse. The forend was slimmer. Some preferred this over the Marlin, but others thought the fatter Marlin forend gave better control. The wood finish appeared to be a synthetic product that filled the pores completely. No linseed necessary here. Again, a decent trestle-style buttpad was there to help cut the kick.

The action was as smooth as that of the Marlin, and again there was no looseness or rattling on the rifle anywhere. The Henry was fitted with a large aperture rear sight and a flat-top post front. The aperture was adjustable via opposing screws for windage, and by unscrewing the rear aperture post for elevation. The aperture post was locked by the windage-adjusting screws. Half a turn gave approximately an inch of elevation change at 100 yards. More on that later. The rifle weighed 7.3 pounds empty, half a pound more than the Marlin.

The front sight had a vertical groove or slot formed in its rear face, and it had white paint in it. The color could be easily changed as desired. This line helped us see the front blade in some kinds of light. The aperture was essentially a ghost ring. The eye does not see it in sharp focus. While it might be too big for really precise shooting, the rifle was set up for extremely fast use in the field, and in that light the sights were superb. Nitpicking, we would have liked to have both the front and rear sight elements set lower on the gun, or perhaps a straighter stock to get our eye up higher. We ended up having to raise the rear sight significantly, which made it even more of a neck stretch. At any rate, the sights were fast as lightning. Poke the rifle at the target and all you see is the front post. Our bench testing would tell us what kind of accuracy we could expect, though we doubted the Henry with this setup would be a tack driver.

Next was the question of the Henry’s safety. The hammer was either all the way cocked or all the way down. As we prepared to log the rifle in, our Idaho FFL man Joe Syczylo was muttering and grumbling about something to do with the Henry. He said, “There’s no safety of any sort on it.” We agreed there was nothing obvious about how to manage the hammer to prevent accidental discharges. The Henry manual stated that the rifle could not be fired unless the trigger were pressed on a cocked hammer. A blow on the lowered hammer could not move the firing pin and therefore would not set off a chambered round. If the hammer were to accidentally slip while being cocked, the gun could not fire. We proved that to our satisfaction by putting a primed cartridge case in the chamber and repeatedly slipping the hammer off our thumb just before it reached full cock. Nothing. We then cocked the hammer and pressed the trigger, and the primer fired. However, lowering the hammer on a loaded chamber was not quite as foolproof as with the other two rifles. We suggest you practice it with an empty rifle. You have to hold the hammer securely and press the trigger until the hammer moves slightly forward, then release the trigger and lower the hammer fully. If the hammer slips off your thumb with the trigger pressed, the rifle will fire, so always be careful.

On the range we were able to load four rounds into the tube, which operated just like a tubular-magazine 22 LR. Pull out the brass tube with its spring and plunger, expose the hole in the magazine, and drop in the rounds. There is no stop on the brass tube. It will pull all the way out, and in fact that’s how you unload the magazine, which is a handy feature. It was possible to load one in the chamber and another into the tubular magazine, but that puts one’s hand in front of the muzzle of a loaded rifle. We didn’t like doing that, so called it just four rounds capacity, which Henry also does. No 4+1 here.

As expected from the coarse sights, this was not a tack driver. We got groups of 2.5 inches with the Winchester and 3.5 inches or so with the Remington at 50 yards We thought that was acceptable for hunting accuracy at limited range on big targets. Of course this was not intended to be a long-range tack driver. We suggest Henry give some serious thought to providing a screw-in, smaller aperture within the existing ghost sight ring. Then there should be no complaints. As we received the rifle, we found the sights to be way low. The Remington 405-grain bullets struck 8 inches low, and the lighter, faster Winchester rounds printed a full foot low at 50 yards. To get the Remington ammo on the paper at 50 yards, we turned the aperture up eight full turns, and that did the trick. Of the three rifles, this is the only one that showed a preference for the Winchester ammo. The other two shot their smallest groups with the heavier-bullet Remington stuff.

Our Team Said: Once again we found ourselves liking this rifle a whole lot. We suspect we’d take a file to the tall front blade if we owned this and had found that our chosen ammo printed too low. But we’d have to proceed with caution because the front-sight blade and base are integral with the front barrel band. The trigger pull was very much okay, and the action, feeding and ejection were all smooth and positive. Unloading this rifle was easier than most tubular-magazine rifles, and a bonus was that the bolt could be easily taken out to clean the rifle from the rear. An instructive video came with the rifle explaining the entire takedown procedure. The workmanship and finish were beyond fault. The accuracy could be improved, we’re sure, with a scope or smaller aperture if needed. Pretty much everything here was done just right, and the cost was reasonable.

Winchester Model 1886 Limited Series45-70 Government, $1340

Winchester’s website shows only the “Short Rifle” version of the 1886 available today. The Short Rifle has a 24-inch barrel. Our test rifle’s is 26 inches with its recessed crown, and it was apparently a good deal thicker, too. Winchester gives the weight of the Short Rifle as 8.5 pounds, but our rifle weighed 9.6 pounds. Two inches of barrel would not weigh anywhere near a pound, so we guessed the barrel on our test rifle is also bigger across the flats. This rifle has “Limited Series” impressed into the barrel, so we assume you may not be able to get one of these just anywhere. From the literature that came with it, Winchester has arranged with wholesaler Davidson’s, Inc., of Prescott, Arizona, to produce this limited series of rifles.

More’s the pity that you can’t get them everywhere, because this was a really beautiful rifle that anyone would be proud to own. For instance, the flats on the octagonal barrel were done perfectly. They had no waviness, just a smooth, shiny blued surface all in one plane from end to end, with the corners of the flats just off of being sharp, i.e., extremely well done. The sides of the action were equally flat, begging for the touch of an engraver.

The wood was solid, dark walnut with good strong grain running in the right direction. The matte finish on the wood appeared to be epoxy. It was water repellent, hard, and had no open pores. The wood-to-metal fit was, we thought, the best of the three rifles. The best fit of all here was on the steel crescent buttplate, which appeared to have the wood grown to fit it. The wood and metal fitting and workmanship was, everywhere, just phenomenal. We seldom see new guns made this well these days.

One feature the Short Rifle had that ours did not was that it was tapped for a side-mounted rear aperture sight. Ours had the original-type rear sight with huge “buckhorn” ears obscuring half the landscape out where the target would be. The huge U of the rear had another small U at the center. Elevation was adjusted by the spring and wedge system. For windage, both the front and rear sights were dovetailed into the thick barrel. The front sight was a tiny gold bead with, horrors, a rounded rear face that we predicted would give us fits on the range. There was no provision for a hood. Light bounces off rounded sights in a manner that’s not predictable. A file might be able to fix that in a hurry, but we didn’t own this one. Anyway, we thought we’d try it first before we did too much complaining.

There was a slight bit of sideways movement of the lever when the gun was closed. That was, we thought, insignificant compared to the sound and feel of the lever in operation. There was a positive “thunk” and a velvety smoothness to it that overshadowed the other two rifles. There was no checkering on the wood, which we believe is in keeping with original Winchester rifles. The higher grades used to have it, but not the working-man’s 45-70. The original Winchester 1886s were made from 1886 to 1935 in what eventually became a handful of different calibers, largest being the 50-110. Today it’s 45-70 or nothing.

Like the Marlin, the Winchester had an auxiliary safety. This was a smooth little tang-type, and again it permitted lowering the hammer (rebounding) in perfect safety. Unfortunately, the sliding tang safety was located where holes could have been drilled for a folding aperture rear sight. So one is faced with either using the sights that are on the rifle or drilling and tapping it for a suitable side-mounted rear sight.

On the range our 50-yard groups averaged just under an inch with the Remington ammo and 2.5 inches with the Winchester HP ammo. With the Remington ammo, the shots centered in the X ring with no adjustment needed. The Winchester rounds struck 2 inches higher. The massive barrel kept differences in recoil pulses and bullet-weight impact differences to a minimum on the target. The lever stuck closed after firing the first of the Winchester rounds, but we were unable to repeat that, and marked it off to a burr or tiny piece of dirt we didn’t catch in our pre-shoot cleaning. The rifle felt really good, like a precision piece of machinery, and contrary to our expectations, the tiny gold bead was easy to see and gave a very good sight picture. We disliked the huge ears up in the air, but the sights did perform. Because of the rifle’s apparent very fine accuracy potential, some might be tempted to fit an aperture rear sight, but for fun shooting, we’d leave it entirely alone. The trigger pull was clean and fully predictable despite its pull weight.

Our Team Said: This was a fine rifle in all respects. It cost more than the other two, might be harder to find, and was not in the same class as them for portability. The 1886 was never designed to be a handy guide’s rifle. It felt great, looked great, and would provide many years of fun shooting along with ample pride of ownership to anyone lucky enough to find one.

Written and photographed by Ray Ordorica, usingevaluations from Gun Tests team testers.