We wanted to take a look at 357 Magnum double-action revolvers with 4-inch barrels and adjustable sights because these handguns are so versatile. They can be juiced up with hot 357 Magnum ammo to hunt black bear from a tree stand or kept in the night stand drawer for home defense. They also allow for plenty of training with less powerful 38 Special ammunition, or they can be used competitively in an IDPA match.

288

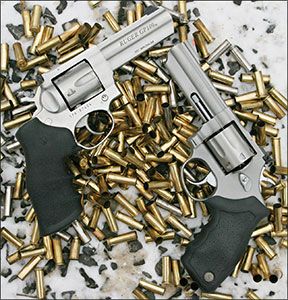

Two such wheelguns that fit this description are the Ruger GP100 No. 1705 357 Magnum, $759; and the Taurus Model 66 No. 66SS4 357 Magnum, $591. Both have transfer-bar firing systems, wherein the blow from the hammer is transferred via the transfer bar to the firing pin located in the frame. To determine which handgun we preferred, we battered this pair with all the 38 Special and 357 Magnum ammo we could scrounge. The results were close, but features of one made it a little better, in our estimation.

Background

The Taurus Model 66 has been around since the 1990s and shares a similar design with Smith & Wesson revolvers, since S&W’s parent company has a majority share in Taurus. There are four Model 66s listed on the company’s website in blued and stainless finishes and 4- and 6-inch barrels.

The GP100 has been part of Ruger’s lineup since 1986. Ruger lists five different models in the Standard GP100 family with barrel lengths of 3, 4, 4.2, and 6 inches. Finishes are either blued or stainless steel. Manufacturer’s suggested retail prices range from $699 for the alloy steel models to $759 for the stainless-steel 357 Magnum revolvers. All models come with Hogue Monogrips.

They are chunky, heavy revolvers built like the proverbial brick outhouse. That extra weight makes the GP100 a pleasure to shoot, even with hot 357 Magnum ammo, we found.

Cosmetics

From all outward appearances, the 66 seemed like any other single-action/double-action revolver. The matte-stainless-steel finish was well executed. The hammer and trigger were more brightly finished. The 66 was a smart-looking revolver.

On the Ruger, the sights, grooved barrel and grips, as well as a satin stainless-steel finish gave the Ruger a refined look and feel. The Ruger mixed squared edges, such as at the trigger and the hammer, with graceful lines on the barrel and behind the GP100’s cylinder.

Capacity

Crack open the 66’s cylinder, and the chambers look off. Reason: The 66 is a 7-shooter, not the typical 6-shooter like the Ruger. Testers liked the fact there was an extra round in the cylinder without bulking up the gun. The diameter of the cylinder for the Ruger and the Taurus were 1.65 and 1.62 inches, respectively, so Taurus squeezed in the extra round by putting less metal between chambers in the 66. Advantage Taurus.

Fit and Finish

With clean, unloaded revolvers, we checked the barrel/bore alignment with each chamber using Brownells 38/357 Service Revolver Range Rods (#080-617-038WB, $40 at Brownells.com), and we found all the chambers were in spec. The Ruger had a tighter cylinder locked with the hammer cocked back; the Taurus had a barely perceptible wiggle. Not a show-stopper, however.

The teardrop-shaped cylinder latch on the 66 was small and well textured. It was easy to operate and use with a speed loader. The cylinder latch on the Ruger was housed in a recess in the frame.

The end of the eject rod was knurled on the 66; the GP100 was smooth. Both revolvers have a triple lock up cylinder: center pin rod, detent in the crane, and cylinder latch (in Ruger parlance) or a cylinder stop (S&W/Taurus). These three lock the cylinder from the rear, front and bottom, respectively.

Both barrels sported a full lug that completely shrouded the ejector rod. On the 66, the muzzle end of the underlug was tapered back to make reholstering easier.

The Ruger one-piece frame is easier to disassemble than the Taurus, but don’t lose the small pin which holds the mainspring compressed. If you do, a paperclip works in a pinch. Both use a coil spring for a main spring.

The Ruger revolver did not offer an internal safety lock like the Taurus. Instead, the Ruger came with a padlock designed to pass through a single chamber with the cylinder swung away from the frame.

Sights

The 66’s black rear sight was adjustable, with arrows and “UP” and “R” nomenclature indicating elevation and windage directions, respectively. A white outline made the notch more visible. The clicks in the 66’s rear sight were not as definite as those on the GP100, we thought. The top side of the 66’s barrel presented a matte finish, which allowed for glare-free sighting in bright sunlight. The ramped front sight was machined from the barrel stock, and a red insert in the ramp made target acquisition easy, our shooters said.

Testers felt the rear sight of the GP100 was better because it was built into the Ruger’s frame, protecting it more, though that protection bulked up the GP100. A very small screwdriver was required to turn the Ruger’s windage-adjustment screw. The front sight on our Ruger was a black ramp grooved to reduce glare and dovetailed into place. Shooters preferred the sights on the Ruger.

Triggers

The Taurus trigger shoe was wider than the Ruger’s. Both triggers surfaces were smooth. DA pull on both revolvers felt smooth, though some noted that the 66’s DA pull felt slightly less than the GP100’s, even though the Taurus DA pull broke at slightly more than 10 pounds. The GP100’s DA pull broke at 10 pounds on the nose on average.

If we short-stroked the triggers in fast DA mode on either revolver, the mechanism froze. We had to allow the trigger to move fully forward to reset the mechanism. This is a design trait and a reminder to shooters who aspire to shoot like Jerry Miculek.

At the Range

The bore centerline of the Ruger was slightly higher than the Taurus, but there was no extra perceived muzzle flip, our shooters said. The wheelguns merely used two different design approaches, both of which worked to our satisfaction.

Taking a high grip on the 66 allowed shooters to easily manage the recoil and get back on target fast. The recoil was manageable, though the hotter 357 Mag loads gave more perceived felt recoil in the palm of our hands.

The finger grooves of the Ruger’s rubber grip were more pronounced, yet fit average to large-size hands exceedingly well. The 66’s rubber grips had a pebbled texture with a slight palm swell and finger grooves that actually worked with a variety of hand sizes. Rubber covered the entire frame, so there was always rubber between our hands and metal.

Loading seven rounds into the 66 broke the rhythm of loading two rounds at a time, but we soon became acclimated to the extra round. The full-length ejector rod shucked empties from the 66’s cylinder with ease. Using 38 Special loads, we shot Impact Seal Bouncing targets (do-alltraps.com) as fast as we could as the cube or ball moved with each subsequent round.

Our Team Said

The Model 66 lacked some of the Ruger’s finer features, but for the cost and the extra round, we would buy it for trail carry and home defense. Because the grips were flat, it could also be used for concealed carry.

In rapid fire, the Ruger was very controllable and a pleasure to shoot due to the weight. However, carrying that weight on the trail or around town isn’t going to be what most shooters want. If money wasn’t a concern, our team would prefer to buy the Ruger GP100.

Written and photographed by Robert Sadowski, using evaluations from Gun Tests team testers. GT