Toward the end of each year, I survey the work R.K. Campbell, Roger Eckstine, Austin Miller, Ray Ordorica, Robert Sadowski, John Taylor, Tracey Taylor, and Ralph Winingham have done in Gun Tests, with an eye toward selecting guns, accessories, and ammunition the magazine’s testers have endorsed. From these evaluations I pick the best from a full year’s worth of tests and distill recommendations for readers, who often use them as shopping guides. These choices are a mixture of our original tests and other information I’ve compiled during the year. After we roll high-rated test products into long-term testing, I keep tabs on how those guns do, and if the firearms and accessories continue performing well, then I have confidence including them in this wrap-up.

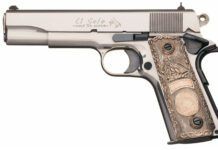

Many civilian carriers have adopted shorter and lighter 1911s of the Commander size. The original Colt Commander featured a barrel and slide -inch shorter than the 5-inch Government Model. The Commander pistol also had an aluminum frame, making it lighter. The shorter pistol is also faster from the holster, and though the short sight radius may limit absolute accuracy, the Commander lines up on target quickly at combat ranges. Our Best of Class Pistol is one such model, the 4-inch-barrel aluminum-frame Kimber Pro Custom Defense Package (CDP) II 45 ACP, $1331.

Because of its expense, it’s no surprise that the CDP was well put together and showed attention to detail. This loaner had perhaps 7,500 rounds on the frame but only showed a bit of wear on the KimPro finish. The trigger originally broke at just over 4.5 pounds and had settled into a crisp and smooth 4.25-pound break.

The Kimber featured a stainless slide and low-mount sights with tritium inserts. The pistol featured the aforementioned ambidextrous safety. This was one of the better designs, smooth and snag free and positive in operation. The pistol featured a useful beavertail safety and mainspring housing checkering. The Kimber showed an advantage in the frontstrap checkering with a very nice 30-lpi treatment. The pistol also featured checkering under the trigger guard. This added touch results in good purchase when the two-hand grip is used.

The Kimber incorporated a full-length guide rod into the design. The owner noted that he may quickly remove the slide intact with the spring and rod attached — you can do that with the full-length design, but not a GI gun. Just the same, this is a personal choice, not an issue. The belled barrel was 4 inches long with a bushingless lockup. Velocity loss was negligible compared to 4.25-inch barrels.

The combination of grip checkering and the fit and checkering of the rosewood grip panels made for a handgun that was controllable in rapid fire, but not as docile as the steel-frame guns. The recoil sneaks up on you. After firing 50 rounds of full-power ammunition, you realize you have done a fine job on the paper target and fired a great run on the combat course, but that your wrists are sore. After 100 rounds, the shock is more apparent. This isn’t the pistol to work over the course with +P loads. It will take the jolt, but the shooter will suffer.

The Kimber was supplied with two flush-fit magazines. For concealed carry, flush-fit magazines make more sense than extended basepad magazines. During the evaluation we also used a half dozen Wilson Combat ETM magazines. This magazine features a slightly longer body with a heavier spring for greater reliability.

In speed tests, the pistol cleared leather quickly. The Kimber was brilliantly fast on the draw, came on target quickly and got a solid hit in the hands of a skilled user. Heavier recoil made combat groups larger when we approached the 10-yard line, but first-shot hits were just as fast and sure with the Kimber. The cadence of fire is never set by how quickly you are able to press the trigger but rather by how quickly you are able to acquire the sights after firing. With that standard in mind, the Kimber gives up little to the steel-frame pistols.

The Kimber’s groups off a bench-rest were consistent and showed high overall accuracy.

Our Team Said: The Kimber is ambidextrous, accurate, lightweight, fast to target, and dependable. What else is there?

Not long ago the next big thing was the small concealment pistol chambered for 380 Auto. It seemed like every maker was bringing out a small pistol with barrel lengths shorter than 3 inches and an overall size that could fit inside the dimensions of the average adult’s hand. For 2013, Ruger went against that trend and introduced the LC9 re-chambered for 380 Auto — the LC380 — which solves two of the problems associated with the palm-sized 380s: A slightly bigger gun should ease recoil and provide better handling.

We tested an LC380 with 102-grain Remington HD BJHP, 90-grain Federal Premium Hydra-Shok JHP, and 92-grain FMJ rounds from Sellier & Bellot. Our test distance for our accuracy session was 15 yards. In addition to our benchrest session, we also performed an action test. Notes from our shooting session showed that hits from our LC380 were landing about 1.5 inches high on our 15-yard targets. But we found the size of the gun to be very suitable. We found the left-side-only thumb-operated safety to be pleasingly stiff and sure in operation when turning the gun on and off.

The sight picture was quite clear, making good use of its 4.5-inch-long sight radius. Sight radius was maximized thanks to the rear unit seated to match the profile of the rear face of the slide, minus consideration to continue its forward-leaning contour. The steel sights offered a three-dot picture with both units dovetailed into place. The top of the slide was fitted with a loaded-chamber indicator that angled upward when a round was in place.

It might be easy to assume that all “plastic”-looking pistols are made from polymer. But Ruger’s choice of synthetic material is actually high-performance glass-filled nylon, which lends itself well to producing an effective grip pattern. With the alternate basepad in place to extend the grip, we could better accommodate the pinky finger on the LC380.

From the bench, the Ruger LC380 delivered five-shot groups that measured about 1.8 inches in width for every type of ammunition we tried. In our action tests, our first three shots in the practice session took about 2.24 seconds to complete. When we began our shots of record, our first three shots were completed in just 1.86 seconds, then 1.78 seconds, 1.70 seconds and 1.55 seconds. Accuracy for our five strings of fire produced 9 of 15 shots inside the 6-inch-diameter circle.

Our Team Said: The LC380 was completely reliable and fun to shoot. The grip was easily held, and the trigger responded evenly. Ruger’s LC380 is an affordable 380 ACP pistol offering better ergonomics than the smallest pocket 380s and a more-pleasant shooting experience than most 9mm Luger-chambered small guns.

Potent 40-caliber mid-size pistols combine the best of many worlds — power, capacity, and concealability. In May, we looked at one such handgun, the Glock 23 Gen 4 40 S&W (MSRP $650), firing Remington 155-grain JHPs, Black Hills 165-grain JHPs, and American Eagle 180-grain FMCs.

Out of the box the Glock felt mighty good. This version of the popular gun comes with several different back-strap contours that the owner can easily swap out to better suit his or her individual mitt. Neither of the two add-on grips make the grip any smaller, however. We liked the grip as it was. The grips were very well made for control, and we appreciated that right from the start.

The Glock is all flat black, with a minimum of controls. There’s the trigger with its tiny but effective leaf that gives the gun all the safety it needs. We noted the contour of the trigger has been improved, and we liked it. The magazine release is reversible, and worked like it was supposed to. There was the slide stop, left side only, and protected with a molded-in ledge right below it. Finally, there were the take-down levers above the trigger opening. The “levers” are actually two ends of one plate-like piece. There was an accessory rail in front of the trigger guard.

The sights had a wide, square, U around the rear notch and a white dot on the front. Tritium sights are optional items. There was a tactile loaded-chamber indicator in the form of a slight step on the extractor that could be easily felt with the (right-hand) trigger finger. The top edges of the slide were smooth enough to not cut the hands during clearance drills. However, if you do many of them with stiff-spring guns, you’re going to hurt your hands, as we found out.

Takedown was simple. With the gun empty and the magazine out, drop the striker, pull the slide back slightly and pull down on the takedown levers on both sides, and ease the slide forward off the frame. The captive spring comes easily out, and then you can get the barrel and guts as clean as you’d like. Reassembly is even simpler. We like to put some of Brian Enos’ Slide Glide (BrianEnos.com) on the rails. Then, with the barrel and spring in place in the slide, simply slip in back onto the frame and tug on the slide. The takedown levers will click up into place, and you’re ready to go. We thought the workmanship inside the Glock was excellent, just as it was on the outside.

The trigger was decent and clean, and we were able to shoot groups in the 2.5- to 3-inch range with ease at 15 yards. The gun shot essentially where it looked, unlike the Taurus. The groups centered all three test loads within 2 inches of the aim point. The gun got the best groups with the heaviest bullets.

Our Team Said: We liked this gun a lot. It handles the hotter 40-cal cartridges well, and gave exactly no problems.

On August 28, 2013, Springfield officially recalled XD-S 45s with serial numbers between XS500000 and XS686300 because of concerns about accidental discharges and double fires. We tested a new Springfield XD-S 45 ACP, $599, in the December 2012 issue, wondering if full-power 45 loads would simply be too much in the small, lightweight gun. Our test gun wasn’t affected by the recall, so we decided to include the model as a Gun of the Year despite the recall.

The list of features for the XD-S 45 is impressive. Our test gun came in a well-padded hard-plastic case with a hard-plastic paddle holster, dual magazine pouch and Allen wrench to adjust tension on both, two 5-round magazines, interchangeable backstrap, a cable lock, wire bore brush, and extra fiber optics in red and yellow.

The Ultra Safety Assurance (USA) Trigger System guards against accidental discharge by locking the trigger until direct rearward pressure is applied. The new XD-S trigger also has a short reset.

A loaded-chamber indicator allows the shooter to verify, visually or by touch, that there is a round in the chamber. The grip safety allows firing only when the shooter has a firm grip on the pistol. The XD-S disassembles just like the XD, however, with the XD-S, the disassembly lever cannot be manipulated with a magazine in the pistol. Additionally, when the disassembly lever is up, a magazine cannot be inserted into the pistol.

A waffle-pattern grip texture wraps around the frontstrap and backstrap, providing a secure grip surface. The ability to customize the grip with two Mould-Tru Backstraps allows a variety of shooters to find the right fit, regardless of hand size. The rear sight on the XD-S is low-profile and holster friendly, and the red fiber-optic front sight was easy to find and align, our team said. A single-position Picatinny rail accepts lights, lasers or other pistol accessories. A Melonite finish protects against corrosion.

At the range, our shooters said the XD-S seemed heavy towards the front and top — to be expected with the polymer frame and steel slide. It weighs in at 22.6 ounces empty and 26.4 ounces with six 185-grain hollowpoints.

We liked the XDS for self defense because of the large caliber and ease of use. We performed the best in our defense test with it, firing four rounds in 3 seconds with one X, one 9, and two 8s. Our testers liked the three-dot sights, with the fiber-optic front sight, saying it was easiest to acquire the target quickly.

The advantage of this being a 45 and having more stopping power is paired with the disadvantage of the recoil of a 45 ACP in a small pistol. Our testers loved the XD-S at the start of the test, but by the end the stronger recoil had us hurting. After a day at the range, the waffle grip pattern that had provided for such a solid hold on the narrow grip had dug into our hands and left a solid impression. Concealing the XDS isn’t a problem with its small stature, although the paddle holster provided by Springfield is worn outside of the pants, so we don’t recommend it for concealed carry. We preferred a Crossbreed Minituck holster for the XDS and had no issues with concealment or drawing the weapon.

Our Team Said: The Springfield XD-S ranks high on our list as a self-defense and concealed-carry weapon.

New manufacturing techniques are making minute-of-angle bolt guns less expensive and more versatile, too, as an April test of two 243 Winchesters bolt guns showed. Thompson Center Arms’s $679 Dimension rifle offers the ability to accept different-caliber barrels so that the same platform can be used to hunt a wider variety of game. But our testers preferred the Howa Hogue Youth 2N1Combo No. HWR66204+ rifle, $641, which comes with two different stocks so that the same Howa M1500 action will accommodate more than one shooter. Both stocks are manufactured by Hogue. That utility makes it our choice as the Best in Class Rifle

The Japanese-made Howa M1500 action is a standard affair with a four-round magazine above a hinged floorplate. There was a three-position safety so you can work the bolt to empty the chamber with the trigger locked in place. With the safety fully rearward, the bolt would lock in its down position. Both the trigger guard and the supplied scope mounts were aluminum. Otherwise, the Howa featured heavy steel construction.

Both test rifles weighed about 7 pounds, despite the Howa’s barrel being 2 inches shorter and having its youth-sized stock. In addition, the bolt handle was shaved as it left the stock and the knob was hollowed out. The free-floated barrel tapered from about 1.2 inches in diameter at the action to about 0.6 inch diameter at the muzzle. Its crown was recessed. The polished machine lines running perpendicular to the bore were a nice cosmetic touch. We liked the Howa’s clean, no-nonsense look.

Our 2N1 combo model arrived with the smaller of the two Hogue stocks in place. Black in color and referred to as being a “Youth” size, we didn’t feel it was so small that a lot of adults wouldn’t be able to use it. The length of pull was about 12.5 inches, but the height of the buttstock, unlike many youth models, was not greatly reduced from the full-sized stock (about 0.55 inch). The result was that the comb was not too low nor the contact area so thin that it stabbed the shoulder. In fact, the buttpad was as wide as 1.6 inches across.

The Hogue OverMolded stock consisted of a rigid fiberglass-reinforced skeleton fit precisely to the action and bonded both chemically and mechanically to a rubber coating that was molded over and shaped to the desired profile. The result was a stock that is impervious to oils and solvents and will not harden with age. The surface of the stock is rubbery so that grip is enhanced at all points. Grip is further enhanced with a pebble finish at the pistol grip and in a traditional pattern along the forend.

Changing stocks on the Howa was very easy. A number T15 Torx wrench removed two screws. One screw sat behind the trigger guard and the other appeared forward of the magazine floorplate. The trigger guard was removed and then the action. There was also a heavy steel box that comes free from between the stock and the bottom of the chamber. It was open slightly on one end to provide spring tension as it fit beneath the feeding point. Its upper opening was tapered. This was listed as the magazine. Reassembly was not much more difficult than lining up the holes for the Torx screws.

At the range we found the Howa was a model of consistency, averaging a 1.0-inch group for all shots fired. Winchester 80-grain soft points and Black Hills 58-grain rounds produced 0.7-inch groups. Our test staff credited the Howa’s consistency to the trigger. The HACT (Howa Actuator Controlled Trigger) began with a short, free swing of the trigger followed by a brief sense of compression and crisp let-off. A trigger-adjustment screw was indicated in the parts list, but no instructions for the user were included in the owner’s manual.

Our Team Said: The HACT trigger would be a welcome addition to any production rifle. In fact, everything about the Howa rifle was consistent, predictable and easy to operate. The larger O.D. Green “adult” stock was particularly comfortable.

We tested three AR-15s by Rock River Arms, ArmaLite, and Bushmaster in the September issue. The specific gun which earned a Gun of the Year nod in this test was ArmaLite’s M15A4 Carbine No. 15A4CBA2K, $1031. Chambered in caliber 5.56 NATO, it stands out as an accurate and simple example of the type.

We shot the rifles at 100 yards using just two types of ammo. This was Black Hills’ 68-grain Heavy Match HP, and Russian TCW ball (55-grain FMJ) ammo, representing some of the finest and some of the least costly 5.56 ammo available for these rifles.

This ArmaLite rifle looked a lot like the Rock River, but with a slightly smaller (0.720-inch) barrel, measured midway on the exposed portion. It also had the forward-assist button and spring-loaded door on the ejection port.

Our Team Said: On the range this rifle gave us the smallest group we’ve seen in a long time, three shots into 0.3 inch at 100 yards. The ArmaLite M15A4 averaged just under an inch with all the groups fired with the target ammo. The Russian stuff was not bad either, averaging 2.5 inches.

In a September Special Report, Gun Tests shooters happily accepted the assignment of reviewing a hot new number, the Tavor TAR-21 (Tavor Assault Rifle, 21st Century) in a semi-auto civilian rifle. The manufacturer, Israel Weapon Industries (IWI), has opened up a U.S. branch (IWI US) and is manufacturing and assembling the gun in this country. It will accept any standard AR-15/M16 magazine, and the Tavor is available in black or flat dark earth with an MSRP of $1999. The owner of our loaner test gun paid $1850 for his in April 2013.

The Tavor had a 16.5-inch barrel and an overall length of 26.2 inches, which gives the operator the ability to maneuver quickly and shoot with the accuracy of a longer rifle. It weighed 10.2 pounds with a 30-round magazine and an EOTech XPS2-2 Holographic Weapon Sight aboard. Along with the gun, IWI included a belt pouch that contained four cleaning-rod extensions, a squeeze bottle for gun lube, a bore brush, a chamber brush, a general cleaning brush, a large brush for cleaning the inside of the receiver, and a windage/elevation adjustment tool for the front sight. Also, there were a pair of QD swivel studs, a IWI branded magazine, and the owners manual.

The Tavor was ripe with features, starting with the design of the gun. Every piece of polymer on the gun was ergonomically designed and felt great, our shooters said. There are optional conversion kits that would allow the gun to shoot either 9mm Luger or 5.45x39mm. It is 100% ambidextrous with a separate kit, which contains optional left-handed bolts. Sights include built-in back up irons with a tritium-tipped front post.

The barrel on our test gun was chrome-lined and fitted with a standard flash suppressor. The hammer-forged CrMoV (chrome-moly-vanadium) tube had six grooves and a 1:7 right-hand twist. The charging handle was non-reciprocating. A Picatinny rail ran along the top of the gun, which was great for mounting optics. It also comes with a rail on the right side of the gun. The body of the gun was completely made of one solid piece of polymer. The safety was mounted on the pistol grip.

Because most of the Tavor’s dry weight is located on the back half of the gun right around the pistol grip — even farther back with a loaded magazine inserted — it was easy to hold the rifle on target. Even if you had to hold the gun for long periods of time without your front hand, we think it would be relatively easy with this gun. The 1-inch-thick rubber buttpad on the butt of the gun gripped really well and provided the right amount of cushion on the shoulder.

A feature notably different than other rifles was the location of the mag release and bolt release. With some practice, we were able to change the magazine quickly with one hand, all without taking the strong hand off the gun. Even without the front hand on the gun, the shooter could shift his shooting-hand thumb back and bump the mag release, dropping it free while the support hand was grabbing the next one. Once we had a fresh magazine and were ready to insert it into the gun and lock it in place, the support-hand thumb was ready to hit the bolt release. The bolt release can also function as bolt catch if you don’t have an empty magazine to leave the action open.

For accuracy testing, we shot the Tavor off sandbags using standard Magpul AR-15 magazines. We noticed that because of the way the spent shells ejected from the gun, if necessary, a left-handed shooter could operate the right-handed version of the gun and not eat any brass. The Tavor delivered average group sizes at 50 yards (three shots) of 1.4 to 2.0 inches .

Our Team Said: This is a solid bullpup rifle. It fired flawlessly, was light weight, and had great ergonomics. The only thing that we did not like about the gun was the heavy trigger.

In a June test, we acquired two historical and technically interesting firearms: the 9mm Wise Lite Arms Sterling L2A3 9mm, about $500, and the Inter Ordnance/Pioneer Arms PPS-43C Pistol chambered in 7.62×25 Tokarev, $500. Of the pair of fun-shooting carbines, we preferred the Wise Lite Arms Sterling.

The Sterling had black crackle finish on all its metal surfaces except for the trigger group, which was Parkerized. The receiver’s mag well was marked “STERLING SMG 9MM MK4 (L2A3).” Barely visible through the crackle finish on the side of the action tube was “Wise Lite Arms Boyd, TX, Mod. S/A Sterling Sporter Cal 9mm.” The two magazines we received with the gun each held 34 rounds and were the original design, with rollers instead of a simple follower to ensure the rounds feed easily and positively.

The gun had an aftermarket barrel of just over 16 inches length that kept the Sterling legal, in keeping with its semiautomatic firing operation. Everything but the pistol grip was made of steel, pierced, welded, formed, and homogenized into an example of fine British gunmaking worthy of the Crown. When the folding stock is locked in place, there is no motion, no slop, no wobbling at all. With the stock folded, there was again no rattling or slop anywhere.

Inserting and removing the intricate, beautifully made magazines also showed the precision with which this gun was made.

The rear sight was well protected. It was an L-shaped folding aperture with a large hole for 100 and a smaller one for 200 yards. We found that the smaller one was the correct elevation for the height of the front blade, but we had to move the front sight left to get the hits centered. It simply slides in a dovetail. Elevation is controlled by an Allen screw that locks the threaded front blade. To adjust height you loosen the Allen screw and turn the front blade in or out.

On the range we found the gun shot way left and somewhat low with the larger 100-yard aperture turned up. We drifted the front sight left to bring the hits back to center and then used the smaller 200-yard aperture to get just about centered. We didn’t touch the front sight.

The trigger pull was long and smooth, and generally very nice. The accuracy was better than original specs, which called for all hits in 12 inches at 100 yards, or 6 inches at 50. Our best group at 50 yards was 1.4 inches for three shots, but most were around 3 inches on average.

Our Team Said: We thought this was a fine arm, most of all for fun at the range, and also as a valuable icon that shows what good gunmaking used to be.

We picked out two vastly different AK-style rifles for a showdown in the May issue: The WASR-10 imported by Century International Arms and the 556 Russian (556R) made by SIG Sauer. The SIG 556R is a revised version of the original rifle chambered in 7.62x39mm, most commonly referred to as the Gen 1. Gen 2s like our test gun have a steel-reinforced magazine shelf, a wider ejection port, and increased the hammer-spring strength to ignite harder primers in Russian ammo.

An all-black plastic and metal presence gives the 556R a sleek look common to AR-15s. Exterior fit is camouflaged, in a way, since the handguards butt up against the receiver and the folding stock pops onto the back of the receiver. There’s minor looseness to the fit of all the parts, our inspection showed. The lower half of the action wiggles a tad, the buttstock wiggles a tad, and the handguards wiggle a tad, but there was nothing alarming.

The SIG’s Swiss folding buttstock allows the user to shorten the length of the rifle, which is ideal for tactical situations. The SIG’s ribbed-plastic recoil plate was superior to the WASR’s wood stock and sheet-metal buttplate. We preferred the grip on the SIG as well. The ergonomics were better, our testers said, and it had more girth to it, which made it easier to get a grip on. It was textured in a striped pattern on the left and right sides of the pistol grip and was smooth on the back. The bottom of the grip also extends further, which facilitates the ease of maintaining a grip.

The SIG’s flattened polymer operating handle felt better than the plastic-covered steel knob on the WASR, we thought. For accessories, the SIG also had three built-in removable polymer Picatinny rails, two 2.5-inch-long strips on the sides and a 3-inch-long rail on the bottom. For sights, there was a built-in top rail (with a cutout machined for the pop-up rear sight) and a red-dot sight. Also, the 556R came with a bolt lock and an ambidextrous flip safety.

The flip safety is a nice touch; you can easily flick it with your finger to make the rifle ready to fire or on safe. Its smooth design is also much easier on your fingers when operating the rifle. Another plus is that the safety is ambidextrous, and if you don’t mind the brass coming out in front of your face, the gun can be shot left- or right-handed.

With the SIG, if you pull the action open, there is a little lever on the middle of the left-hand side that, when pressed down, locks the action open. If you keep the gun loaded in your house or on your property, this gives you the ability to see that the action is clear. The SIG’s receiver has a Picatinny rail on top that accepts the included SIG Sauer Mini Red Dot Sight (STS-081, $199).

Our Team Said: A finished product, the SIG Sauer 556 Russian comes out of the box ready to work with the 7.62x39mm round.

The 38 Special revolver has long been a standard as a back-up and concealed-carry handgun. As part of our new Bargain Hunter series, we wanted to challenge the conventional notion that a wheelgun chambered in 38 Special should be the de facto winner of any boot-gun showdown simply because it has always won those battles in the past. In the same power range as the 38 Special is the 9mm Luger (aka 9mm Parabellum or 9x19mm), which has the added benefit of being loaded more widely, often at less cost per round, than the 38 Special. On a price-per-round basis, we found more 9mm ammo at a lower price than similar bullet weights of 38 Special. We also found the Charter Arms Pitbull 79920, $465, notable for not needing moon clips to use the 9mm Luger round.

The Charter Arms 9mm Pitbull revolver makes this possible by using a dual coil spring assembly in the extractor that holds a standard rimless 9mm round in place, then ejects it like any other standard revolver.

The Pitbull is not perfect, but it is vastly superior to other 9mm revolvers we’ve tested. The spring-driven ejection system is essentially a built-in moon clip that clamps into the casing groove. This allows a shooter to use the more readily available and cheaper rimless 9mm ammo, if the ejection system works as it’s promoted. We found the ejection system works great if the rod is pushed quickly and the revolver is pointed up at an angle. We did have some spent brass that was less than cooperative, but, overall, the system worked well.

Charter produced the most accurate gun in the test by having clearer larger sights and a much larger grip. The Pitbull was easy to control and we enjoyed testing it, and we believe that as a range gun or training gun, it would be fantastic. It might be too large to carry as a back-up like smaller 38 Specials.

Our Team Said: Taking into account its lower operational costs, the Pitbull is worth considering instead of a 38 Special revolver.

In an April test, we looked at two revolvers head to head that are considered by some to be the best available: the Colt Python and the Smith & Wesson Model 686-2.

The Python is widely regarded as one of the finest production revolvers ever made, and our testing here reconfirmed that. But that quality comes at a price.

So, because of the price barrier, we chose the more affordable Smith & Wesson Model 686-2 357 Magnum stainless six-shooter as a Gun of the Year — that is, one you should go out to buy used.

It is built on S&W’s excellent L-frame with a full-lug barrel. It has a hammer-mounted firing pin, which means it’s a pre-lock design, has no MIM parts, and has its original Goncalo Alves flared wood grips.

The L-framed model had a heavy, full-lug barrel, shrouded ejector rod, relieved cylinder latch, and original Smith & Wesson wood grips with exposed backstrap. The finish was a natural-buff stainless steel.

The stainless-steel frame and barrel and checkered wood grips came together for a classic look. The 4.1-inch barrel was slightly longer than the Python’s, and the wood grips were considerably larger, with a lot of flare at the bottom.

Sights were a stainless front ramp and stanchion machined into the barrel top with an orange serrated insert. The rear sight was fully adjustable. Almost the entire top of the barrel was serrated along its length, providing a glare-free surface. The hammer spur was smaller in both in height and width than the Colt’s, and the trigger was moderately wide, rounded, and smooth.

The Smith & Wesson double-action trigger presented the shooter with excellent feedback. There was clean, motion-free movement of the trigger when fired single-action. Checking bore-to-cylinder alignment with the Brownells match-grade range rod showed no chambers out of time. Smith collectors praise the earlier 686 models because there are no MIM parts and the hammer-mounted firing pin makes direct contact with the primer, rather than the hammer striking a frame-mounted pin.

Our Team Said: We feel that given the price and rarity of the Python, you can’t go wrong with a Very Good, Excellent, or Like New Model 686-2. Make a few inexpensive changes to fit your tastes, and you’ll have a lifelong companion.

The collecting of really old Colt revolvers can easily threaten the bank account, or even shatter it. Today, 2nd-Gen. Colts are scarce, but do turn up from time to time at gun shows. They are not cheap, but sell for a fraction of the cost of the original models, and are considered to be “real” Colts. The 2nd-Gen. Colts took up where the old serial numbers left off, and were in most respects real hand-fitted Colts, though the manufacture of the parts may have been done by a different company. Shooters recognize the differences in the aura of the gun in their hand. In an August report, we looked at three 2nd-Gen. Colts: a Second Model Dragoon, an 1860 Army, and an 1851 Navy, all bearing the Colt name and appropriate Colt serial numbers. We ended up giving all three A grades. Depending on condition, of course, we would recommend adding any of the three to your collection.

We first tested the Colt 2nd-Gen. 44 Cal. Second Dragoon, about $800. This big gun came about to replace the great Walker and also address some of the Walker’s failings. This gun is big and heavy. The upgrades from the Walker include a reduced chamber capacity (Walkers held 60 grains), a badly needed latch at the front of the ramming lever, rectangular slots for the bolt instead of round ones, and a shorter barrel. There were a few minor internal modifications as well. The First Dragoon had the Walker’s rounded bolt stop, but was otherwise much like the Second Model. The gun was really well finished. The brass grip frame was cleanly made with no rounding over, and carried the last four digits of the serial number. The cylinder, frame, grip strap, and barrel extension all bore the full five-digit serial number. The lockup was exceptionally tight. The few modifications done by the owner include gently beveling and polishing the fronts of the cylinder outlets so the seated ball does not get its lead shaved off, but rather gets it swaged inward as it is rammed home, which aids sealing. This was done to all three handguns in this report.

The bluing was excellent, a deep rich color that set off the beautiful case coloring. Also the roll engraving on the cylinder was sharp and clean, with no overstriking and with all the figures visible including the hair on the horses, the bridles, and even the expressions on the men’s faces. The grips were one-piece decent walnut, with an oil finish. They fit perfectly and had enough figure to be interesting.

On the range the big gun did excellent work for us. A group of six shots had all six touching, forming a ragged hole in the paper at 15 yards.

The handy and powerful Colt 2nd-Gen 1860 Army 44 Cal., about $650, represents one of the best weapons of the Civil War. It is far lighter than the Dragoon, more powerful than the 1851 Navy, and somewhat more graceful looking. This one had the original blued backstrap and brass trigger guard of most of the original ones. It also had the cuts in the back plate, protruding frame screws, and a notch on the bottom of the backstrap for the accessory stock. The grips on this one were absolutely stunning. Again, the grip straps, frame, and barrel extension held the serial number. The cylinder had only the last three digits of it. The fitting of the various parts was excellent, with sharp corners, matched planes, no rattling, and generally the feel of a precision instrument.

The cylinder mouths were gently broken to ease loading. The action internals had also been slightly slicked up, we were told. Lockup was tight, and the hammer was far easier to cock than that of the Dragoon. The case coloring was again richly done and brilliant. The roll marking on the cylinder was excellent, but the color of the barrel was a touch on the purple side.

We would be happy to own two of the Colt 2nd-Gen 1860 Army 44 Cals and would have no qualms about keeping them fully loaded as home-protection guns. The 1860 Colt was deadly during the Civil War and will still go a long way toward keeping the bad guys civil.

The classic Colt 2nd-Gen. 1851 Navy 36 Cal., about $650, choice of Wild Bill and many other old Westerners, also did yeoman service in the Civil War. We suspect the great feel of the grip, same as on the later Peacemaker, helped this gun achieve its lofty place in history. The test gun had silver-plated brass grips. The trigger guard was a bit pinched for us. We’d prefer the London Navy or any of the oval-guard versions which have more room for the trigger finger. Despite this gun’s obvious extensive use, the silver plate on the grips retained its unity. The gun had been fitted with Uncle Mike’s stainless nipples that took #11 CCI caps perfectly. Other changes included the beveling of the chamber mouths and the insertion of a screw into the front sight position. The rear sight opening in the hammer had been enlarged, and the height of the hammer cut down slightly.

The fitting was as good on this gun as on the other two. The octagonal barrel had flat flats and sharp corners. The dark walnut grips showed some figure and again looked like they had grown into the metal grip panels. The bluing on cylinder and barrel were deep and rich. The case coloring was dark but rich looking. Of all three of the tested 2nd-Gen. guns, this one felt the most precise to cock. Lockup was again very tight. There was a fitted wood case for this gun, complete with flask and brass bullet mould with cavities for round and conical ball. There was also a period-style holster by Old West Reproductions (OldWestReproductions.com) that was made for the gun. All in all, it was a mighty nice package.

Our Team Said: If you encounter one of these Colts that is in outstanding and still original condition, should you alter it? Probably not, although beveling the chamber mouths is an excellent idea if you plan to shoot the gun. We think changing the original nipples for stainless ones is a very good idea. Just keep the originals. If you choose to alter the front sight you’re on your own, or your gunsmith is. For best investment purposes, an all-original gun will beat the altered ones, and unfired ones are perhaps even better. But then you miss out on all the fun of shooting a real Colt cap-and-ball revolver.

Benelli’s super-lightweight shotguns, the Ultralight line, are touted as being the lightest semi-automatic shotguns in production. We tested a Benelli Ultralight Model No. 10802 12 Gauge, $1649; and Remington Model 1100 Sporting No. 25315, $1211, head to head in the February 2013 issue. We gave both shotguns A grades, but we preferred the Ultralight. The Benelli weighed in at a mere 6.4 pounds, putting the Model 1100 challenger in a different weight class at 8.4 pounds — a 31% uptick. For the pheasant hunter who pushes rather than blocks, that 2-pound savings means a lot.

We became familiar with the two shotguns by dry-shouldering and snap-capping them. One of the first things we noticed was how much lighter the Benelli actually felt, beyond what the scale said. Weighing in at just over 6 pounds and measuring 47.5 inches in length, the Ultralight was very fast to target.

The Benelli Ultralight ships with three screw-in Crio choke tubes in Improved Cylinder, Modified, and Full constrictions. The Ultralight put more lead on the target than the Remington and in a much tighter center grouping. Also, the Benelli is chambered for 3-inch shells, whereas the Remington accepts 2.75-inch shells.

The recoil on the Ultralight was astonishingly low for such a light gun. For most of our team, there was not a perceivable difference between the two guns, and after shooting all afternoon, no one’s shoulder was bruised or banged up.

Our Team Said: Our team would buy the Benelli Ultralight ahead of the Remington 1100 Sporting for general shooting chores, including a light amount of various shotgun games. For heavy-duty target shooting only, we’d give the nod to the Sporting because that’s what it was made for.

At a reader’s request, we selected several new models of self-defense shotguns that carry low to moderate price tags and pitted them against one of the popular veteran self-defense shotguns to see how they would perform. The 12-gauge pumpguns in our October 2013 test included the Benelli Super Nova Tactical No. 29155 pump-action 12 Gauge, $559, and the recently introduced Stevens Model 320 Home Defense No. 19495, $270. The Stevens Model 320 Home Defense was the bottom-dollar model in our test group, but it came up big in performance. Sporting the same length barrel (18.5 inches) and Ghost Ring sights of the Benelli, we were pleased to find the visibility of the chartreuse light-bar front sight through the Ghost Ring was exceptional.

This high visibility also transferred over to patterning performance, with the Stevens always placing 27 out of 27 buckshot pellets in the test target — the top ranking. Several slugs fired at a Bad Guy target from 20 feet hit right in the middle of the character’s forehead and the distribution of No. 6 pellets was quite solid in the target’s chest and head area. Although not as deeply etched into the synthetic material as the grooves in the Benelli, the forearm and full-length pistol grip of the Stevens were easy to hold and provided a steady shooting platform. Even in rapid-fire mode, the shotgun was easy and comfortable to put on target.

Patterned after the discontinued Winchester Model 1300, the appearance of the Stevens is very plain Jane. We were concerned about the effectiveness of the hollow synthetic stock, but found the recoil of the shotgun was no more shoulder shocking than with the other test firearms. The only minor problem we encountered with the Stevens involved the action release located on the left rear of the trigger guard. The release button seemed to be a little small, although it could be worked by all.

Our Team Said: The highly visible sights, patterning performance; and the comfortable, solid feel of the firearm impressed us.

In the December 2012 issue, we selected a 28-gauge version of Benelli’s Ultra Light with a price tag of $1,760 and matched the new kid on the block against a 28-gauge version of one of the most venerable semiautomatics in the country — a used Remington Model 1100 picked up for $1,300.

In addition to the price difference, the two 28s are poles apart in offering a sub-gauge platform for wingshooting and busting clay targets. Like in the 12-gauge test covered earlier, the Benelli is more than 2 pounds lighter than the Remington; features an Inertia Recoil system rather than the gas-operated Model 1100 to reduce shoulder shock; and boasts of a new cryogenically treated barrel and chokes for cleaner shooting and tighter patterns.

We put the two shotguns through their paces on some South Texas mourning dove hunts and a few sessions of sporting clays to see how the youngster fared against the veteran. Test ammunition included Winchester AA Super Sporting Clays loads of 3⁄4 ounce of No. 71⁄2 shot with an average muzzle velocity of 1300 fps; Rio Game Loads with 1 ounce of No. 71⁄2 shot and an average muzzle velocity of 1200 fps; and B&P Target loads with 3⁄4 ounce of No. 71⁄2 shot with an average muzzle velocity of 1280 fps. The Winchesters were used for clays and patterning, while the Rios and B&Ps were the dove loads of choice.

We patterned each of the shotguns with Improved Cylinder and Modified chokes and fired the Winchester ammunition at a 30-inch circle set up 30 yards downrange. The results were as advertised by Benelli, with the Ultra Light producing denser, more uniform pellet strikes with both chokes.

Concerning recoil, no semiautomatic 28 gauge worth its salt will smack the shooter’s shoulder with the authority of a larger 20 gauge or 12 gauge. Both of these shotguns were a pleasure to shoot, with little felt recoil from either model. At best, the recoil factor was a tie between the new lightweight Benelli and the heavier veteran Remington.

At first glance, the Ultra Light almost appears as a miniature version of a sporting shotgun with its slim, short forearm, 26-inch barrel and heft of only 4.9 pounds. It seems designed for youngsters and small women rather than for the lumbering former football linebackers or arm-chair quarterbacks normally found in the dove fields and on clay target courses.

We quickly began to appreciate the feel and balance of the Benelli, which follows the tradition of similar models produced by the Italian company during the past few years. While it is very light, the balance between the hands is very good, and we encountered no problems swinging through targets.

As veteran wingshooters and clay busters know, a light or short shotgun can often result in a whippy or choppy swing through targets, rather than the smooth glide that produces solid hits on birds and clays. That was not the case with the Benelli, and we had no problems center-punching both winged and clay targets.

Only one-half inch shorter than the Remington at 47 inches, the length of pull on the Benelli was 14.25 inches and the drop at the comb was 1.5 inches with a drop at the heel of 2.5 inches. Everyone from the smaller members of our test team to the big bruisers agreed that the comfort factor was good and the handling ability of the Benelli was quite surprising.

The trigger pull was a little disappointing, breaking at 6.5 pounds, with a lighter touch of about 5 pounds preferred by most shooters. Unlike with its larger cousin — the 12 gauge — less recoil from a 28-gauge shell makes the easier trigger touch off not as important a factor.

We found that hits on birds and on clays were very solid, reinforcing what we learned at the patterning range and the balance of the Benelli eliminated any possible whipping of the lightweight shotgun through targets. Unlike with the Remington shotgun, we encountered no functioning problems with any of the tested ammunition.

Following the pattern of other Benelli semiautomatics like the Super Sport and the Cordoba models introduced in previous years, the Ultra Light utilizes an Inertia Driven system that features only three moving parts — the bolt body, the inertia spring, and the rotating bolt head. This system is very effective, and with the cryogenically treated barrel and chokes, did result in a cleaner, more effective way to send lead downrange, our patterning targets showed.

Our Team Said: The performance of the tiny 28 justified the hit to the buyer’s wallet, our testers said.

We took a hard look at almost two dozen 223 Remington loads in the May 2013 issue and found that many are not well suited for personal defense because they don’t offer adequate penetration. Other loads, however, are practically ideal for personal defense. Also, the loads must be reliable in every AR-style firearm or other design chambered for the round, from a Colt HBAR the excellent Ruger Mini-14 rifles. For our test, we used a Bushmaster 16-inch-barrel carbine with Trijicon iron sights. It was a stock set up except for a red receiver plug that tightened things up.

The major areas of downrange performance many people wonder about are: Which load is the most frangible?, and which load offers the best combination of downrange public safety, stopping power, and a lack of ricochet? The only means of arriving at the truth is to conduct a test program that is both repeatable and verifiable. To start, we agreed that reliability is more important than anything else. We fired a minimum of 20 rounds — a magazine full — of each load to gauge reliability. It isn’t a given that all cartridges run well all of the time. Also, we noted any other malfunctions that occurred during the rest of the test as part of the reliability numbers.

Next, we measured both penetration and expansion in our standard gallon-water-jug testing program. In self-defense situations, we can’t expect to have a perfect scenario for a low-penetrating round to do its job. Ideally, we wanted somewhere between 15 and 18 inches of water penetration.

We also conducted an accuracy test using our defense-length carbine, but you may be able to get better results with longer barrels. We shot a number of loads in as many different weights as possible. While bullets of different designs behave differently in the same weight, we felt that the test criteria showed the performance of various classes of loads well. The lightest bullet tested was less than half the weight of the heaviest load, with the weight of the rounds tested ranging from 35 grains to 77 grains.

Our Team Said: The lightest bullet weight that earned an A grade was the Cor-Bon DPX Hunter 53-grain Barnes Triple-Shock X Bullet Lead-Free DPX22353. The next recommended loads were the Black Hills Remanufactured 60-grain JSP M223R4, Hornady TAP FPD 60-gr JSP 83288, and Hornady TAP Barrier 60-grain JSP 83286LE. Heavier bullets did well as a group, with A grades going to the Cor-Bon DPX Hunter 62-grain Barnes Triple-Shock X Bullet Lead-Free DPX22362/20, Black Hills Remanufactured 77-grain Sierra MatchKing HPBT M223R9, and Buffalo Bore 77-grain HPBT S22377. Several other loads earned A- grades, including the Winchester Super-X Power Max Bonded 64-grain Protected Hollow Point X223R2BP, Black Hills Remanufactured 75-grain Match Hollow Point M223R6, and Hornady TAP 75-grain JHP 80268.

If you want penetration, the Cor-Bon DPX loads at 53 grains and 62 grains are outstanding. As a blanket recommendation for home or area defense, the best results begin at 60 grains, and in particular the Black Hills M223R4 load, which was among the most accurate loads in the test, penetrated 14 inches in water, expanded to .44 caliber, and retained 78% of its original weight. For those particularly concerned with overpenetration, the Cor-Bon 55-grain BlitzKing or the Black Hills 60-grain V-Max are first-class choices.

Among the heavier loads, the readily available Black Hills 77 grain is a top choice. The Buffalo Bore 77-grain loading is virtually equal to the Black Hills load.

In a January 2013 test of alternate 1911 loads in 9mm, 38 Super, and 10mm, we recommended a number of products. Our favorite 9mm load was the Buffalo Bore +P 124-gr. 24F/20. Among the heavyweights, we liked Cor-Bon Self Defense 10mm Auto 165-gr. JHP 10165, Cor-Bon DPX 10mm Auto 155-gr. DPX10155, and Hornady 10mm Auto 155-gr. XTP 9122.

Our Team Said: But the best balance of shooting comfort and downrange performance came with the 38 Supers, in particular the Wilson Combat 38 Super +P 124-gr. XTP A38SU-124-XTP and Cor-Bon Self Defense 38 Super +P 125-gr. DPX DPX38X125/20 (shown above).

A February 2013 comparison of 10 40 S&W loadings asked if the 40 S&W really splits the difference between the 9mm and 45 ACP cartridges. We checked some data from recent tests to get a feel. A Remington Golden Saber 124-grain JHP 9mm we previously tested produced 1145 fps velocity, 360 foot-pounds energy, expanded to 0.57-inch diameter, and penetrated 12.5 inches in water. A Black Hills 45 ACP 230-grain JHP traveled 875 fps and produced 386 foot-pounds of energy. It expanded to a 0.72 inch diameter and penetrated 13.5 inches in water. In this test, a Black Hills 180-grain JHP (@ 1009 fps) walloped the 9mm and topped the 45 samples in energy, producing 406 foot-pounds (12% more than the 9mm and 5% more than the 45). It showed expansion to 0.70 inches and 20 inches of water penetration. It seems to us that the 40 is much closer to the 45 than the 9mm in performance. That is a good place to be.

Our Team Said: The favorites were the Black Hills D40N220 180-grain JHP, Winchester’s PDX1 Defender WINS40SWPDB 165-grain HP, and the Black Hills D40N120 155-grain JHP, which was called a Best Buy and is pictured below left.

Are the 22 Magnum and 32 Magnum cartridges credible alternatives to the 38 Special as self-defense rounds? Probably not, but many people use those rounds for self defense anyway, so in the July issue, we wanted to see which ones offered the most penetration and expansion despite their lower power numbers. During the firing tests, our test team noted how controllable the 22 Magnum was — one rater was able to fire the single-action 22 so quickly he was able to put three bullets into the jugs before the water drained, with the three bullets resting neatly in place at the bottom of the third jug.

Our Team Said: Of the loads in the test, only one 22 Magnum round earned a recommendation: the Hornady 45-grain Critical Defense FTX #83200. This Hornady load, shown expanded at left, is among a very few loads specifically designed for use in a short-barrel handgun and it shows. Bullet weight is ideal, and the bullet expanded reliably and retained all of its weight. Bullet expansion was very uniform. The Hornady Critical Defense load is ideal for use in a self-defense handgun.

In contrast, both 32 Magnum loads earned A grades: the Black Hills 85-grain JHP D32H&RN1, and Federal Personal Defense 85-grain JHP C32HRB. If you cannot handle a 38 Special for one reason or the other, the 32 Magnum may be an option.

In the August issue, we compared the performance of the 357 Magnum revolver round against a 9mm pistol because, for defensive use, most carriers choose the 9mm for its low recoil, good control, and adequate downrange ballistics. 9mm ballistics have improved considerably, with some loads operating at +P and +P+ pressures and topped with great bullets. At the same time, the 357 Magnum is no longer limited to heavy revolvers; relatively light five-shot revolvers with short barrels are widely available. So, if we compare the handguns that are purpose-designed for defense use, does the Magnum really have that great an advantage? To compare 9mms to 357s, we selected a half-dozen loads in each caliber shot from handguns representative of the types actually carried for personal defense.

Our Team Said: If you are willing to deploy at least a K-frame revolver with a 4-inch barrel, the 357 might offer a significant advantage in downrange power. In the end, for the shooter interested in a good personal-defense pistol, the 9mm loaded with the best modern +P load seems the better choice, in our opinion.

Among the 357 Magnums, Cor-Bon’s 110-grain JHP SD357-110 stood above the best as an A+ load. Five other loads earned A grades: Glaser Pow’rball 100-grain PB 357100, Winchester USA 110-grain JHP Q4204, which was named a Best Buy (right), Speer 125-grain Gold Dot HP 23920, Federal Premium Personal Defense Reduced Recoil 130-grain Hydra-Shok JHP PD357HS2 H, and the Winchester Super-X 145-grain Silvertip JHP X357SHP.

The 9mm loads that got A+ ratings were Buffalo Bore’s +P 124-grain JHP 24E/20 and Winchester’s +P Ranger T 124-grain RA9124TP. Grade A loads were the Black Hills 115-grain EXP JHP D9N620, which was also a Best Buy (right), the Cor-Bon 115-grain JHP SD09115/20, Hornady’s Critical Defense 115-grain Flex Tip eXpanding 90250, and the Hornady Custom 124-grain XTP JHP 90242.

Among the most-popular concealed-carry handguns is the 9mm compact pistol, in part because in the same frame size, the 9mm is more powerful than the 380 ACP, and when compared to a similarly sized wheelgun, most 9mms offer more shots than a 38 Special. But many carriers who like the portability of a small 9mm pistol with a lot of shots worry how the 9mm compact’s terminal ballistics compare to the same rounds shot out of a full-size gun. Because the 9mm relies upon velocity to instigate bullet expansion, a significant loss of velocity may be ruinous to a bullet’s performance. The issue is important because the once-obscure German service-pistol cartridge is now the most popular semi-automatic carry-pistol caliber in America.

We tested several loads in a SIG Sauer P290 with a 2.9-inch barrel, representative of the breed of short-barrel 9mm pistols, to see which ones we’d buy.

Our Team Said: Among the 115-grain loads, we said the Fiocchi 115-grain Extrema Hornady XTP JHP 9XTP25 had good control, accuracy, enough penetration, and a great price, which gave it an A grade and made it a Best Buy. We preferred the 124-grain loads overall, with the Speer Gold Dot 124-grain +P Short Barrel JHP 23611 getting the top grade in the test with an A+. The Gold Dot design is tweaked for extra performance in the short-barrel gun. The +P rating increases velocity over the standard Gold Dot, and the bullet features a softer core. Expansion and penetration were excellent. This is a solid choice for all-around use. Expansion is the greatest of any load tested, and accuracy was excellent. Grade A loads included the Black Hills 124-grain +P JHPD9N920 and the Winchester Supreme Elite +P 124-grain PDX1 JHP S9MMPDB.

Throughout 2013, we found a number of accessory choices that are worth noting. In particular, we tested holsters heavily during the year, with one of our favorites being the Liberty Custom Leather Savannah, $50 (shown right). In the April 2013 issue, we looked at leather inside-the-waistband models, because the IWB has the advantage of concealing the major part of the pistol inside the pants. In this review, we tested seven holsters from five makers, all molded for the 1911 Commander-size pistol. Among the Grade: A units were the Milt Sparks Summer Special, $90; the High Noon Tail Gunner, $210; Liberty Custom Leather’s Savannah, Freedom Line, $125; Barber Leatherworks S and S Model (Snaps and Straps), $120; and the Liberty Custom Leather Savannah, $50 (shown above).

Our Team Said: The most demanding concealed-carry handgunners will choose the High Noon or the Barber Leather Works designs because each accomplishes real stability, one with a tailgunner fin and the other with dual wings. The Summer Special is a classic design with much to recommend it, but it’s more complex than it first appears. The Wild Bill holster is often found on the rack at gun shows, so it’s availability is a big plus. The Liberty Custom Leather Savannah is very nice in the Freedom Line, but the standard version does as well for less.

In the August 2013 issue, we looked at IWB holsters again, this time adding Kydex and hybrid styles. A hybrid holster has both leather and Kydex, usually with the leather as backing and the gun sheath being Kydex, but the term is also applied to leather holsters with a Kydex paddle.

A reader asked if we could do a test of IWB holsters and come up with the best balance of speed, retention, and access between Kydex, leather, and hybrid types — a tall order, so the South Carolina test team put these holsters to the test. The holsters were worn for a minimum of a week and tested by drawing for at least fifty repetitions. We looked at a number of considerations to come up with what we liked the best and what we believe will work the best for most people. But as we found out, everyone is different.

For our consideration, we deemed access and retention to be the most important points. Holstering the handgun with one hand after drawing is also important and was given considerable weight during the test program. Comfort is subjective, but quality isn’t subjective when something comes apart, so quality and durability are serious concerns. The quality of mounting hardware is also important. The mounting hardware cannot break easily, and it must fit correctly.

Our Team Said: The A-Rated holsters included the Hopp Custom Leather Holsters IWB, $120; the JM Custom Kydex IWB Holster Version 2 IWB2, $75; Old Faithful Holsters Inside-the-Waistband Hip Gun Holster, $75; and the SwapRig Holsters Revolution, $70, a hybrid which also earned a Best Buy nod (shown above).

In the November issue, we tested four shoulder holsters from Galco, the Jackass rig, VHS, Miami Classic II, and Classic Lite models. Galco International (USGalco.com) began making gun leather in the late 1960s as the Famous Jackass Leather Company in Chicago, Illinois. Their most famous product was a shoulder holster referred to as the Jackass Rig worn by Don Johnson in the second season of the 1980s hit show Miami Vice. Later, Johnson’s character, Detective James “Sonny” Crockett, was fit with a new model from Galco, the Miami Classic.

Our Team Said: We preferred the Galco Classic Lite, $93 (above); followed by the Galco Jackass Rig, $165.

In the September issue, we looked at belt-slide holsters, basically a sleeve of material through which the carrier pushes the muzzle of the handgun, leaving the nose of the sidearm and the grip uncovered and the middle of the gun secured by the sleeve, aka the slide. Many criticize the design because it doesn’t protect the muzzle or front sight, the gun can be pushed up when the user sits, the gun can be noisy when it hits against chairs or other hard objects, and the carry arm can be insecure if the slide isn’t snug on the frame and slide. Despite these worries, belt-slide holsters are among the most popular holster types.

As for the balance of speed and retention, the speed of the type cannot be disputed; it was the retention that worried us. The belt-slide holsters tested proved to be very fast on the draw. The better examples featured good retention for a minimum of leather. For use under a light jacket with a short-barrel handgun, these holsters have merit. The problem of positioning the handle away from the body to allow a good sharp draw is solved to an extent by some of the holsters, and the draw angle makes for good speed in others.

Our Team Said: A-Rated products included the Pink Pistol Holsters Belt Slide Custom Order, $75; Liberty Custom Leather 4X Belt Slide, $50; Milt Sparks Holsters #88 Mirage, $95; and Old West Reproductions #101 Bachman Slide, $110. We picked two models as Best Buys: Wild Bill’s Holsters Radical Belt Slide, $60 (top), and the Don Hume Leathergoods J.I.T. Slide, $30 (bottom).

In the January 2013 issue, the Bushnell Fusion 1600 ARC 10×42 Laser Rangefinding Binocular, $999, was the best mixture of price and performance, in the view of our testers. The Fusion 1600 has three targeting modes: scan, Bullseye, and Brush. While on scan, the rangefinder works like many other finders. On Bullseye, a target icon appears in the display and allows the user to acquire distances of smaller targets. A crosshair appears around the target icon, indicating the distance of the closer object has been ranged. In Brush mode, the rangefinder ignores brush and tree branches so only the distance to the target beyond the brush is displayed. A circle appears on the brush icon when the farthest object is acquired. .

The Bushnell rangefinder includes a proprietary ARC (Angle Range Compensating) program. ARC has two modes, either bow or rifle, which hunters liked.

Our Team Said: What the Bushnell lacked in optical quality, it made up for in price and performance. Many users liked the bright display and the features and gave it an A.GT