For six years, I was an attorney for a national firearms legal-defense program. I represented gun owners who acted in self-defense and traveled the country speaking on firearms issues. I’ve taken countless questions regarding a person’s legal right to self-defense. Over the years, I started to see a pattern — people have the same questions. From your brand-new gun owner to the seasoned carrier, the questions and misconceptions were the same. I’ve heard it all, and nothing catches me off-guard, so I’ve drawn on these experiences to put together the top 10 misconceptions gun owners have when it comes to their self-defense rights.

10 Common Misconceptions About Gun Ownership

1. Drag The Body Into The House

Please don’t. Tampering with evidence is a crime! Do not remove or manipulate anything that could be considered evidence. Evidence is any physical material or intangible information relating to the incident that will be used to ascertain the truth. A body, gun, witness statements/testimony, or video/audio surveillance are all considered evidence.

A defensive use of deadly force outside of the home is not automatically an illegal act. Violent crimes occur every day in public places where defensive deadly force may legally be used. The underlying issue is whether the person using deadly force acted reasonably, given the specific set of circumstances. If it comes to light that evidence was manipulated, not only is that a separate crime, but it makes a person look unreasonable and not justified in their use of deadly force.

Why is this a common misconception? It may be because of the popular legal concept called the Castle Doctrine. Virtually every state has its own version of the Castle Doctrine, which justifies a homeowner’s use of deadly force against an unlawful intruder entering his or her home. In any use of force or deadly force scenario, a person must act reasonably. In Castle Doctrine situations, where an intruder unlawfully enters an occupied habitation, the homeowner is given a powerful presumption of reasonableness. This is an incredible legal protection because prosecutors are hesitant to pursue criminal charges against a homeowner who uses deadly force against an intruder. Plus, it will be hard to find a jury who will convict a homeowner who used deadly force to defend his or her family. Prosecutors hate losing cases.

With that said, people find themselves the victim of violent crimes outside of the home and are legally justified in using deadly force in self-defense. There is absolutely no need to touch or drag anything anywhere!

2. The Only Time a Gun Should Be Displayed Is If You’re Going To Shoot It

Many in the gun community disagree with this statement. In my legal opinion, if a person draws his or her weapon, there is no requirement to shoot. There is a big difference between a display and a discharge, both practically and legally. Legally speaking, a display is typically considered the use of force, as opposed to the use of deadly force. For instance, under Texas law, if a person displays a firearm with the sole intent of creating apprehension in another person to deter further action, Texas considers this display to be the use of force — not deadly force. However, there are several states, such as Virginia, that say the threat of deadly force, such as a display of a firearm, is considered deadly force under the law. Every state’s law is different, so be sure to check your state’s specific stance on this issue. A discharge of a firearm in the vicinity of another person, whether the intent is to scare, injure, or kill, will likely be considered the use of deadly force under the eyes of the law in any state.

Depending on the situation and state law, a person may be justified in using force, but not deadly force. In other words, it could be perfectly legal to display a gun in self-defense to deter a potential attack, but a crime to pull the trigger. Every day, violent crimes such as robbery, sexual assault, and aggravated/armed assault are deterred by the mere production of a gun. Once that gun is pulled in self-defense, the likely result (hopefully) is the perpetrator will think twice before continuing an attack. The goal is simple — to stop the threat.

There is no legal difference between a display and brandishing of a gun. Different states use different terms of art. Both terms describe the presentation of a gun to another person in a threatening manner. Whether a person pulls his shirt up to reveal a concealed handgun, pulls a gun from a holster and points the barrel towards the ground, or points the gun at another person, it will likely be considered a display/brandish of a firearm. The takeaway here is that if a gun is pulled in self-defense, there is no requirement to pull the trigger.

3. Make Sure There Is Only One Side of the Story

Absolutely not! This statement advocates for unjustifiable murder. Potential attacks may be deterred by the display of a gun. A successful defensive display does not end in death. There will be the law-abiding gun owner’s story versus the perpetrator’s story — two sides. If I had to take a wild guess, those two stories will be vastly different. The credibility of each individual will be evaluated throughout the duration of the legal process. First, the police will make their own judgments, right or wrong, about a person’s statement regarding the sequence of events. Second, a prosecutor and defense attorney will evaluate these statements. Finally, a judge or jury will be the ultimate arbiter of credibility and determine whether they believe a person acted reasonably in displaying or discharging their firearm in self-defense.

Even if deadly force is used and the perpetrator dies, there may be witnesses to the incident. This means there could be several versions of the same story even without the perpetrator’s version. If there is a witness or witnesses who corroborate your story, the more credible you become to law enforcement, lawyers, and potentially a jury.

Not convinced? Take the 2014 murder conviction of Byron Smith in Minnesota. Two teenagers broke into his home. Smith set a recorder on a bookshelf to capture the incident. Three shots ring out, leaving one teen dead. Next, several more shots are fired, wounding the second teen. As she is screaming, Smith follows with another shot killing the second teen. When the teen was wounded and no longer a threat to Smith, no further force or deadly force could be legally used. The final “kill shot” was a life sentence in prison for Smith. This case may have turned out differently if there would have been “two sides of the story.”

4. It’s Legal to Shoot a Trespasser

The exact opposite is true. It is illegal to shoot a trespasser. Many people believe this is a situation that the Castle Doctrine covers. If you learn nothing else from this article, learn this: The Castle Doctrine does not apply to trespass on property, but rather to an unlawful entrance into the occupied habitation. See the difference?

A trespass occurs when someone unlawfully enters or stays on property. For example, a person who walks past a “No Trespass” sign and enters the property is committing a trespass. Or, a person enters property lawfully and subsequently is told to leave. If the person remains on the property, they become a trespasser. It is not lawful to use deadly force in either of these scenarios. A lawful property owner may be able to physically eject a trespasser from his or her property, or call law enforcement to handle the situation completely. Many times, a threat to involve law enforcement will have the intended consequence of terminating the trespass.

If the facts are changed, legal rights change. If a trespasser pulls a crowbar from a backpack and begins to charge toward you, does that make them more than a trespasser? Yes! They are a trespasser, plus an attempted murderer. That is a completely different scenario than someone unlawfully occupying property. If a trespasser charges toward you with a crowbar in his hand, it is reasonable to believe that individual is going to either put you 6 feet under or in the hospital. If that is the case, you may use deadly force to protect yourself. But, remember, this is someone committing more than a trespass. With a trespass alone, deadly force is not lawful.

5. Invoking the Right to Remain Silent Will Cause the Police to Think You Are Guilty

If the police are suspicious that a crime has been committed, they will have those suspicions whether a person invokes his or her right to remain silent or not. The Bill of Rights delineates ten individual liberties that this country was founded upon. Wars have been fought and lives lost over these rights. Use them! As Americans, we covet the First and Second Amendment, but let us not forget about the Fifth. The Fifth Amendment protects against self-incrimination. In 1966, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled a person must be apprised of their ability to speak with an attorney before and during questioning by law enforcement while under arrest. This is known as the Miranda warning. If a person is under arrest, plus the person is being interrogated, police must Mirandize the person by stating he or she has the right to remain silent and the right to consult with an attorney before making any statements.

Most law-enforcement officials will agree that people talk themselves into an arrest. If a statement is made that does not match the physical evidence or contradicts another witness statement, an arrest is likely. It is law enforcement’s duty to secure the scene and collect evidence. They will punt the collected evidence over to the District Attorney’s Office, who will determine whether charges will be brought. Police do not make the ultimate determination of charging an individual with a crime; they only have the power to arrest. What happens subsequent to an arrest is completely up to an assistant district attorney. Law enforcement simply advises the assistant district attorney on which route to take. Sometimes the assistant district attorney listens; sometimes the ADA doesn’t. The main takeaway is that you may get arrested. However, being arrested is not the same as a conviction. It is safer to keep your mouth shut rather than having to explain “what you really meant” a year later in trial.

After using deadly force, the human body undergoes several physiological changes. Adrenaline dumps into the blood system, causing tunnel vision, loss of feeling in extremities, uncontrollable shaking, and temporary memory loss. Immediately following an incident is not the time to give a detailed statement. Especially a statement that a person is going to be married to for the duration of the investigation and criminal legal process. Many law-enforcement agencies have a policy for their officers not to give a statement for 48 hours following a police-involved shooting. A person is not doing anything that a police officer wouldn’t do themselves by invoking the right to remain silent.

6. Shooting to Wound Is Better Than Shooting to Kill

This statement is cringeworthy. As noted above, when the trigger is pulled in the vicinity of another human with the intent to threaten, that act will likely be considered the use of deadly force under the law. A person must be in a situation where they would be legally justified in using deadly force in response to the perpetrator’s action. Whether the discharge results in a complete miss, an injury, or a death, it will probably be considered the use of deadly force. It all comes down to whether the shooter acted reasonably in discharging the firearm in self-defense. A judge or jury will be the ultimate decider that determines this issue. If a person is shooting to wound, they shouldn’t be pulling the trigger at all.

7. Criminals Get Arrested; Not Good Guys

This statement is half right. Criminals do get arrested; however, good guys can be arrested as well. In my experience, it is as easy as one contradicting statement from another witness, usually a third party bystander with no relationship between the shooter and the shot. The bystander will give a statement to police that goes something like this: “Yeah, I saw Person A shoot Person B. He just shot him out of nowhere.” The bystander has no knowledge of the events leading up to the defensive response Person A took, or any other surrounding circumstances that went into Person A’s decision to use deadly force. Based upon that one statement, police may decide to arrest Person A. I’ve seen it happen.

Police must have probable cause to arrest an individual. Probable cause is a somewhat low legal standard and is very wishy-washy. It is described as articulable facts that lead law enforcement to the belief that a crime has been committed. In other words, one statement can land another in the county jail.

It is important to remember that just because someone is arrested does not mean he or she is guilty of a crime. As mentioned, it takes probable cause for a person to be the subject of an arrest. To be convicted of a crime, a jury or judge must find beyond a reasonable doubt that a person committed a crime. These are two very different legal standards. The “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard is the highest legal standard in American jurisprudence, while the “probable cause” standard is more toward the bottom of the list.

8. Gun Modifications and Choice of Ammo May Cause More Legal Liability

No, not really. A lighter trigger pull, night sights, or a tactical flashlight are all popular modifications. These modifications can make a gun more comfortable and more effective defensive tools. Loading a handgun with full-metal-jacket bullets as opposed to jacketed hollowpoints does not make someone blood thirsty. Gun owners should not lose sleep stressing about the “increased” legal liability of a modified handgun or the type of ammo used. It is not outside the realm of reality to imagine a prosecutor stating, “Your client is a killing machine waiting to happen with that 3-pound trigger pull!” In a self-defense scenario where an individual used a modified handgun to protect himself, as an attorney, I would not be bothered by that fact. There are several safeguards that may be utilized to attempt to keep that information from the jury during trial. The argument made to a judge prior to the jury being seated is that the modified handgun had absolutely nothing to do with why the defendant used deadly force. The focus must be on the circumstances surrounding why the defendant used deadly force — not the tool used. Whether it be a baseball bat, a knife, or a gun, the only question that must be answered is: Did the defendant act reasonably, thus justifiably, in using deadly force in self-defense? It’s the use of deadly force that is on trial; not the gun.

Even if it does come out to the jury that a person used a modified handgun, there may be gun owners on the jury who have made similar modifications to their own self-defense tools. Or, an expert may testify to the efficiency and other benefits of a modified handgun. At the end of the day, choose the weapon and ammo that is best for you and your hands.

9. A Person Cannot Be Sued Civilly for Acting in Self-Defense

This statement is laughable. Of course a person can be sued civilly! Anyone with a little bit of time and a filing fee can file a lawsuit. The United States has an “open court system,” meaning anyone can bring a lawsuit for any reason. Civil lawsuits are typically brought by a plaintiff to recover monetary damages from the defendant. There is not a gatekeeper at the civil courthouse tasked with determining which lawsuits are frivolous versus legitimate ones. This means a person will have to answer the lawsuit, usually with a general denial of liability, and attend a hearing before the court.

There is some good news. Many states have a civil immunities clause protecting individuals who were justified in using deadly force; i.e., in self-defense or defense of others. This civil immunities protection stops plaintiffs from being able to recover monetary damages from a defendant. It does not stop a potential plaintiff from filing a lawsuit, as mentioned above. Hopefully, the case will land in front of a judge who understands the civil immunities protection, and who will dismiss the case quickly.

10. Warning Shots Are a Great Idea

Nope. Too many well-intentioned gun owners learn the hard way that warning shots are a terrible idea. Many find themselves in handcuffs and very confused as to what they did wrong. Shooting to scare in a scenario where deadly force is not justified will end in a conviction — a felony conviction. A felony conviction means a person can kiss his or her gun rights goodbye. A pardon or restoration of gun rights after such a conviction are extremely hard to come by unless, perhaps, you have friends in the upper echelons of politics.

Warning shots may unintentionally aggravate a bad situation. For example, Person A fires a warning shot at Person B for refusing to leave Person A’s property. (Remember, deadly force cannot be used to terminate a trespass.) Person B, in fear that Person A is trying to murder him, pulls his handgun, shoots and kills Person A. This is probably not the outcome Person A anticipated. Alternatively, a neighbor sees Person A shoot Person B. Neighbor intervenes and pulls her gun on Person A in defense of Person B. Person A is held at gunpoint until responding law enforcement arrives to arrest Person A. It is very doubtful that Person A foresaw this scenario as a consequence of firing a warning shot.

As the adage goes, what goes up, must come down. Where does that projectile land? In the ground? In the perpetrator? In you? Or in a girl scout? You see where I am going with this. It could result in not only criminal liability, but also civil liability. The injured, innocent third-party bystander is going to, rightfully, attempt to recover damages such as medical costs, loss wages, or even emotional distress damages from your pocketbook. On day one of gun-safety training, it is taught to know your target and what is beyond that target. This rule confirms warning shots are a bad idea not only legally, but tactically as well. Where that bullet lands is purely the responsibility of the shooter.

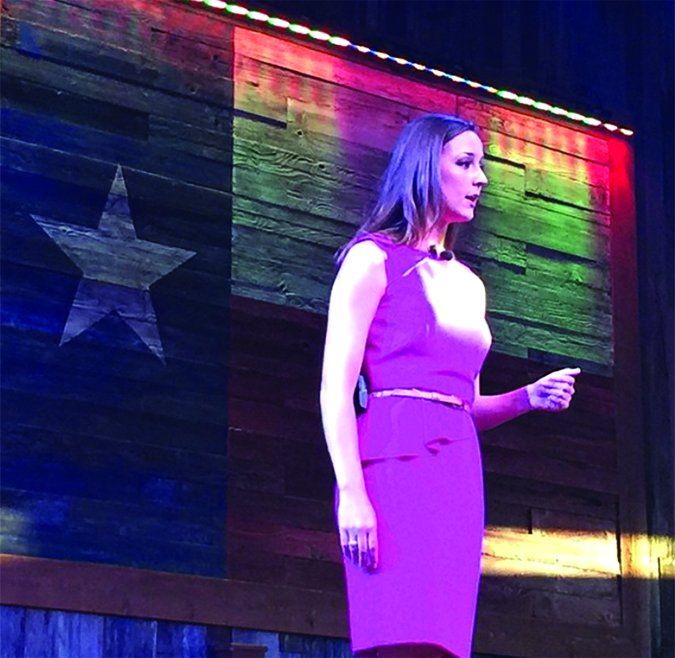

Michele Byington specialized in self-defense cases as an attorney in Houston. She has a Texas License To Carry and prefers Glocks.