We recently read The Book of Two Guns, The Martial Art of The 1911 and AR Carbine, by Tiger McKee. McKee is the proprietor and headmaster of the Shootrite Firearms Academy (shootrite.org) located in Langston, Alabama. Printed in long hand with illustrations, McKee instructs and inspires the reader to consider what skills are necessary to effectively use the handgun and rifle weapon interdependently, as well as in transition from one to the other.

With the two-gun concept in mind, we decided to go ahead with a story weve been considering for some time-evaluating two pairs of handguns that could also be used to work effectively in tandem, in this case, two revolvers against two pistols.

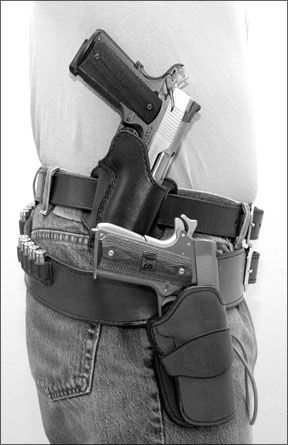

In each pair, we picked one gun that was larger and better suited for primary carry, be it for duty or concealment. The other was significantly smaller and meant to be hidden in case of emergency. Each pair belonged to the same system, or as close as we could supply.

For primary carry we chose two 45-caliber weapons, Rugers $836 Redhawk 45 Colt Model KRH454 and Springfield Armorys $785 Mil-Spec Full Size Stainless 1911A1. Paired with the Ruger revolver was the $450 32 H&R Magnum Smith & Wesson Airweight J-frame Model 431PD. To run with the Springfield, we added a $699 9mm Walther PPS semi-automatic, which was light weight and super slim.

We could have selected any number of pairs of handguns to fill out our test roster. It is interesting to note that our four guns are each chambered for a different caliber. Certainly when it comes to a primary gun there is more leeway in choice. But when it comes to deep concealment larger calibers demand bigger, stronger and heavier frames. Bigger bullets can also limit capacity. Therefore we felt that system and size was more important than matching caliber.

Our test ammunition was as follows. The 45 ACP was represented by Magtech 230-grain FMC, Hornady 185-grain JHP/XTC, and Black Hills 230-grain JHP+P ammunition. The 45 Colt test rounds for the Ruger were Winchester 225-grain Silvertip HP, Federal Champion 225-grain semi-Wadcutter hollowpoints, and Black Hills 250-grain roundnosed flat points. The 9mm ammunition was 125-grain HAP rounds from Atlanta Arms and Ammunition, Black Hills 124-grain full metal jacketed rounds, and Federals 105-grain Expanding FMJ ammunition. For the 32 H&R Magnum ammunition we chose Federal Personal Defense 85-grain JHPs, Federal Classic 95-grain lead semi-wadcutters, and Black Hills 85-grain JHP rounds.

How We Tested

Our method of test began with firing from sandbag support. The primary guns were tested from a distance of 25 yards. Backup guns were tested on targets placed 12 yards downrange. We also spent time firing standing offhand at close-in targets 7 yards away. In addition we looked for clues regarding effective holstering and alternative modes of carry. Here is what we learned.

Springfield Armory Mil-Spec

Full Size Stainless 1911A1

PB9151LP 45 ACP, $785

For many gun owners self-defense begins (and ends) with the 5-inch-barreled 1911-style pistol. Our Mil-Spec Full Size Stainless was a handsome retro-style example of the breed.

Features that distinguished it as such were most notably the sights, hammer, and grip safety. It also had a lanyard loop at the base of the mainspring housing. The trigger had a solid profile and was actually rather short in reach. The left-side-only thumb safety was minimal in platform. The light-colored wood grips added charm by showing the letters “U.S.” carved into the center of each panel amid the checkering. The slide showed rear-only cocking serrations, and the sides of the pistol were shiny and flat. The label of “old slabsides” suited this pistol.

Recoil was handled by a short standard-length guide rod. The top end could be removed without using a bushing wrench. One seven-round magazine made of polished stainless steel was provided.

In terms of looks we knew we had a old-style pistol. But we hadnt taken into account how the retro-features would affect performance and operation. In the past we have encountered olde-style 1911s that functioned only when loaded with ball or full-metal-jacket roundnosed ammunition. But our Springfield functioned perfectly with every round we tried. Furthermore, no malfunctions were encountered when we chose to feed ammunition from modern eight-round magazines by Wilson Combat and Chip McCormick.

Throughout our firing session we alternated ways of loading the chamber. Using several different magazines we alternated our charging method from manually racking the slide to beginning with slide locked back and releasing the stop. The Springfield fed reliably every time. Nevertheless, certain features dictated our shooting technique.

The arched mainspring housing filled our hands. But it also hindered our ability to hold down the grip safety. The arch caused the contact surface to be tucked away from the inside of our palms. Some hands will be meaty enough to press the safety down every time, but some of our test shooters had to modify their grips. A flat mainspring housing would have been preferable, but consider the following:

Todays 1911 shooter likes to ride the thumb safety. But when the thumb was applied to the platform on the Mil-Spec safety, this caused the grip safety to release. Grip safeties found on modern 1911-style pistols are seated higher and deeper into the frame. The modern grip safety also has a raised surface for better contact. This innovation, known as the memory groove, has been credited to gunsmith Ed Brown. To fire our pistol consistently, we had to use a low grip with the thumb riding below the safety. With our shooters concentrating on compressing the thumb safety, they found it difficult to concentrate on tracking the sights and pressing the trigger.

The front sight itself was small and snagproof. But we doubt the term snagproof was even used until the first attempts to adapt taller target sights to holster carry failed. Combined with the shallow notch rear sight, we were thankful that it was a bright sunny day at the range for our tests. In dim light the supplied sights might be useless.

Elsewhere, the trigger was the heaviest weve found on a 1911 in a long time. However, we could find no hint of creep or grit in the trigger. The press consisted of a short takeup to a 10-pound resistance that softened just before it gave way.

To make it easier on ourselves from the bench, we finally decided to fix the grip safety in the compressed position. We began firing with the Magtech 230-grain FMC rounds. Our groups averaged about 4.0 inches with little variation in size. The Black Hills +P ammunition was more accurate, despite recoiling much heavier. Our groups ranged in size from 2.8 to 3.9 inches across. The disparity was largely due to the shooters inability to control the gun consistently.

Muzzle energy produced by this round was about 100 ft.-lbs. more on average compared to the 185-grain Hornady JHP/XTP ammunition. The thrust of the slide pushed the supplied recoil spring to the limit of its ability to return the gun to battery without hesitation. The lighter recoiling Hornady rounds afforded more control to the shooter and helped us print groups that were less than 3.0 inches across. Considering that the sights were barely adequate and the trigger was quite heavy, we thought this performance was remarkable.

In the rapid-fire tests our staff yearned for varying degrees of custom changes. Certainly, there are 1911s available at every stage of development for tactical or competition use. Packaged as it was, the Springfield Armory Mil-Spec Full Size Stainless would first be limited to the hands that can operate the grip safety. But it does illustrate that the 1911 platform-even in its most basic configuration-is a formidable defensive handgun.

Walther PPS WAP10001 9mm, $699

We chose the Walther PPS to represent the concealable semi-automatic in this test because it is thin and relatively light. The letters PPS actually stand for Police Pistol Slim. The PPS is not a single-action-only pistol, but at least its double-action-only trigger is consistent and not complicated by a decocker. Like the single-stack 45, its flat profile promoted a natural index.

The PPS has a polymer frame and hefty top end, producing a total weight of 19.6 ounces. A 40 S&W caliber PPS is also available, and it is listed on the Walther website as being only about 1.5 ounces heavier.

(We should mention that finding the Walther website can be tricky. The address takes up about three lines of text. The easiest way weve found to visit the Walther website was to go to smith-wesson.com, scroll down to the bottom of the page and click on the tiny print that reads Walther America.)

One reason why the PPS is so narrow is that the magazine release is not operated by a button mounted on the grip. Instead, it was integrated with the lower rearward arc of the trigger guard. The magazine release can be pressed from either side. We preferred to use the middle finger of the strong hand to push it down.

When we practiced reloading the PPS, we came upon a problem with the Walther Quick Safe removable backstrap. This feature served two purposes. One was to accommodate different-size hands by supplying two different-size backstraps. The other purpose was to offer a built-in security device. By removing the backstrap, the trigger was deactivated. With backstrap removed, the trigger could still be pressed but it was disconnected from the striker. Once pressed with the backstrap removed, the trigger was seized in the rearward position. Replace the backstrap, rack the slide and the trigger was reactivated.

One issue with this design was that storing the gun without the backstrap in place to make it “safe” or “secure” meant youve got to keep the backstrap somewhere. The gun can be stored without the backstrap in place and magazine in but the magazine would have to be removed to properly reseat the magazine. We toyed with the idea of drilling a hole in the backstrap and attaching it to a key ring. But other problems we discovered could be more serious. Slipping the backstrap panel onto the gun takes more coordination than might be available under stress. Removing the panel does not require a tool. The user only needs to press the tip of a leaf spring exposed at the bottom of the grip. The panel is held in place by the integrity of this spring. The spring is polymer. Will it break or lose tension over time? We cant say, but we did find that a clumsy reload, wherein the edge of the magazine touches the lever, can activate the release, allowing the backstrap to fall to the ground. Thats game over for this gun. To avoid this, we would glue our favorite backstrap into place.

The front of the PPS grip frame had a single crosscut for attaching an accessory light or laser. But it will have to be a smaller model because available rail space was limited to 1.3 inches. The slide showed high-visibility white-dot sights front and rear. The rear unit was marked with the number 2 and the front blade with the number 4. So there must be some adjustment available from Walther, but extra sight blades were not supplied.

The trigger face included a safety much like the Glock Safe Action design. When the striker was cocked, a red dot appeared through a hole in the rear of the slide. Chamber indication could be checked visually through a relief in the barrel hood. Releasing the top end for field stripping and cleaning required pulling down on two latches on either side of the frame while shifting the slide about a quarter-inch to the rear. This was again very similar to the Glock design. If the latches were pulled down with the action already cocked, the trigger needed to be pressed to release the slide. If the striker was not ready to fire, the top end could be removed immediately after pulling down the latches without pressing the trigger. Reassembly was just a matter of running the slide back on to the frame. With the top end removed, we noticed that the recoil assembly appeared to be bowed as it sat in place between the front of the slide and the retaining lug beneath the barrel. This unit was a plunger style dual spring design. The point of flex seemed to be where the smaller tube joined with the larger one that fit over it. A bunching in the springs that ran over each tube magnified the slight deflection in the alignment. We would be more comfortable with a sturdier assembly.

The PPS arrived with two magazines. One held six rounds and the other seven. An eight-round magazine is also available. The six-round magazine fit flush with the bottom the grip. The seven-rounder added an oversized base pad that made room for the shooters pinkie and one additional round. We began our tests with the seven-round magazine in place. Over the course of about 150 rounds we suffered three malfunctions. Each time we found a round in the chamber and an empty case that had not fully ejected. The first malfunction happened firing from support. The second two happened during our rapid-fire tests with the gun held in only one hand. We changed to the six-round mag.

We continued our tests and fired in excess of 200 additional rounds shooting both weak hand only and strong hand only. Despite our best efforts, we could not replicate the earlier malfunctions with the six-round magazine in place. Observations by our staff were that the shorter grip created by the six-round magazine was more comfortable, and even though our pinkies were underneath the bottom of the magazine, we felt we had more control. Another observation was that when loading the seven-round magazine that the follower was sticky. We disassembled and cleaned the magazine body and follower. It wasnt very dirty, but once cleaned it did seem to move more freely. In the end we were not able to ascertain the exact cause of the problem. Our seven-round magazine may be the only seven-rounder in the world that causes problems. Or the PPS may be best suited for 6+1 capacity. We only know that the PPS was fully reliable and easier to shoot with the shorter, more concealable magazine in place.

Testing the PPS at 12 yards proved that the Walther was accurate and easy to shoot. It was also easy to hide, and we could acquire it quickly from concealment devices such as a belly band. From the bench we felt that the Walther PPS was the most rewarding handgun in the test and our data backs this up. All three test rounds produced in excess of 300 ft.-lbs. of muzzle energy. Our most powerful 9mm round was the Federal Personal Defense 105-grain expanding full metal jacket ammunition. These rounds produced an average size group of 1.3 inches across. The Atlanta Arms and Ammo 125-grain HAP rounds, which were topped with a conical shaped hollow point, were even better and printed a sub-1-inch group. Our full metal jacket rounds from Black Hills were nearly as accurate.

While some pistols like the Springfield Armory Mil-Spec Full Size Stainless cry out for upgrades, we think the Walther PPS may need simplification and less, not more, engineering. Innovations such as the Walther Quick Safe backstrap may be completely unnecessary in our view (so too the extra capacity magazines). With such pitfalls easy to avoid, we really liked the Walther PPS.

Ruger Redhawk KRH454 45 Colt, $836

If we could somehow bend history so that gunfighters of the Old West had access to modern double-action revolvers, we wonder which ones theyd choose. Wed bet that the Ruger Redhawk chambered to launch big 45 Colt bullets would be popular. Sized between the Super Redhawk and the GP100 series, the Redhawk is a large revolver. Redhawks favored by hunters can sport barrels up to 7.5 inches long. The size of our Redhawk was minimized by its 4-inch barrel, abbreviated underlug and a Hogue rubber grip that exposed the backstrap. Constructed of stainless steel with a brushed finish, the Redhawk we tested was an impressive sculpture of a sidearm.

Due to its heft the Redhawk might be considered strictly for duty or open carry. But that doesnt mean it cant be concealed. Holsters such as the ITP Ultrux Mirage ($75 from hoffners.com) are ideal for hiding big wheelguns.

Weighing in at 46 ounces, the robust frame was topped with an adjustable rear sight. The front was a ramp blade grooved to reduce glare with an orange-colored insert.

One feature unique to Ruger revolvers is the cylinder release. The left-side-mounted release looked like a button, but it was actually a lever operated by pressing inward. The ejector rod was shielded by the underlug, where it rotated freely without having to take part in cylinder lockup. There was, however, an extra detent on the crane that slipped into a notch on the inside of the frame. This feature was well hidden and could easily be missed.

We liked the Hogue grip on the Redhawk. In terms of recoil we didnt feel any discomfort as one might expect from an exposed backstrap. This was because 45 Colt recoil can be heavy without transmitting a sharp impact. Much of the recoil was expressed as muzzle flip. The grip filled most of the hand with shock-absorbing rubber. The finger grooves were helpful, and the fact that the gap behind the trigger guard was filled removed any possibility of hitting the knuckle of the middle finger. But if the supplied grip is not to ones liking, that should not be a problem. There are more reasonably priced grips available for revolvers than any other type of handgun.

At the range the Federal 225-grain lead semi-wadcutter hollowpoints were the most powerful rounds we tried, averaging nearly 400 ft.-lbs. of muzzle energy. But the 225-grain Winchester Silvertip HP rounds were the most accurate. We could depend on the Silvertips to produce groups measuring about 2.6 inches across on average. Our other ammunitions printed groups just greater than 3.0 inches in diameter. Our bench session was performed single action only. There were times during the test that we had difficulty pulling back the hammer and rotating the cylinder for the next shot. Naturally, we had this same difficulty at times during our double action only session. The troubling aspect was that when not loaded, the cylinder cycled freely. Another observation was that it never happened on the first shot.

At first we wondered if heat or debris were causing certain mechanical tolerances to bind. Finally, we discovered that the cylinder was unlocking upon recoil and allowing the cylinder to rotate, sometimes just a few degrees. This put the ratchet out of position just enough to stall or seize rotation of the cylinder. Another problem we encountered was during the ejection of spent cases. We would push on the ejector but the cases would not fall free. Instead, the star would retract partially and lock on to the cases holding them suspended behind the cylinder. These are issues that should be addressed by the manufacturer under warranty but any double action revolver that resists rapid fire and a speedy reload is not acceptable. Accordingly, we flunked the gun.

Smith & Wesson 431PD 32 H&R Magnum, $450

Shortly before testing this revolver we learned that the 431PD, or rather all Smith & Wesson 32 H&R Magnum caliber revolvers, would be going out of production. This was strange because we had acquired this revolver only recently. In fact its arrival had been postponed, making it too late to participate in our most recent 32 caliber revolvers published in our April 2008 issue. A check of online sites such as gunsamerica.com had two brandnew 431PDs listed for $459 and $499 respectively. According to Smith & Wesson their final suggested retail price was $450. We chose to continue testing because the gun is still widely available and the 431PD nevertheless accurately represents the category of backup revolver.

The J-frame revolvers are the smallest wheelguns made by Smith & Wesson. Some J-frames have a shrouded hammer to prevent snagging on clothing and promote pocket carry or deeper concealment. Some have the hammer completely enclosed. Some are made entirely from steel. Other models are built on frames of titanium, or like our 431PD, utilize an aluminum-alloy frame. The 431PD cuts a more traditional profile because the hammer was left exposed and can be thumbed back for single-action fire. The PD suffix is shared among Smith & Wesson revolvers that are Parkerized, or black in color. Graphics include the Smith & Wesson logo and the word “Airweight” on the right side just above the trigger guard. The subtle dots visible on the left side map out where the support studs are located inside the frame.

The six-round cylinder was deeply fluted. These indentations between chambers served to lighten the gun and reduce the amount of energy needed to turn the cylinder. The backstrap of the grip was indented to reduce mass. So was the outer surface of the trigger guard. The ejector rod was fully shrouded but rather short compared to the cylinder. A J-frame could be set up with a full-length ejector rod, and chamfered cylinders to speed up reloading but these modifications are generally performed on a primary carry gun and not a backup revolver.

The grip found on the 431PD was the Bantam rubber grip by Hogue. It slipped on without the need for a screw. It had a palm swell and a couple of finger grooves. It also filled the gap between the frame and the trigger guard. This was actually a smaller version of the grip found on the Ruger Redhawk. The very bottom of the grip captured a small rod that ran across the indentation of the frame and served as a lanyard loop. The sights were rudimentary. The front sight was a ramp that was lined to reduce glare. As small as this ramp was it was actually taller than the front sight found on the big Springfield Armory Mil-Spec Stainless 1911A1 pistol. The rear sight was a notch in the top of the frame enhanced by a dished area to diffuse light at the very rear of the top strap. Some Bullseye competitors still use “sight black” to black out the sights and shut out glare. The finish of the 431PD makes the entire gun a veritable shadow. There will be no telltale glint of light to spoil the surprise should you suddenly draw this weapon.

Our accuracy tests were performed double action only. Cast in the role as a backup gun we felt that this was the way the gun was meant to be fired. We did, however, utilize a controlled press. This meant the shooter pressed the trigger until the cylinder rotated and locked. The press was continued until the shot broke. Group sizes printed by the 85-grain Black Hills hollow points ranged in size from 1.5 inches across to 2.2 inches measured from center to center. The 86-grain Federal JHP rounds produced groups ranging in size from 1.6 to 2.0 inches and the 95-grain Federal lead semi-wadcutters printed groups varying in size from 1.7 to 2.8 inches across.

In our rapid-fire tests the mix of recoil and the torque of the cylinder starting and stopping placed a premium on shooter skill. The key was to get a high grip on the gun. This meant placing the web of the strong hand as high on the backstrap as possible without being struck by the hammer. This is why we see many revolvers set up with the tang of the hammer shaved off, reduced or, “bobbed.” This also helps avoid snagging on the inside of a garment. We should note that the supplied grip was a compromise that favored concealment over control. Depending on your mode of carry we recommend applying the largest grip you can conceal.

The power of the 431PD was limited by its ammunition and short barrel. Energy available from our test rounds was topped by the 85-grain Federal ammunition. Computed to produce 185 ft.-lbs. on average, this may pale in comparison to bigger guns and calibers but six rounds of this ammunition delivered at close range should change the fight. Frangible rounds are also available.

1008-Springfield-Armory-Mil-Spec.pdf