Snub-nosed revolvers have barrel lengths of 3 inches or less measured from forcing cone to crown. But taking a look at the roster of available snubbies, we found precious few 3-inch wheelguns available. The last one we covered was a hi-tech titanium and scandium model from Smith & Wesson, the 386SC Mountain Light. But what about blue-collar, working-class steel six-shooters?

Well, we found two that fit the bill. Sturm, Ruger and Co., has been quietly producing its GP-100 line of six-shot .357s for years, and we acquired a 3-inch variation, the KGPF-331. Also, we had two to choose from in the Smith & Wesson catalog. The model 64 looked good, but we opted for the model 65LS, the Ladysmith. We thought it was time that “Dirty Harriet” got some press.

How much difference is there between the Smith & Wesson and Sturm, Ruger products? Are they merely two different ways to achieve the same end? Our main concern was to find out if we could make a case for the 3-inch .357 being a better all-round gun than the shorter barreled snubbies or the bigger 4-inch traditional models. Here’s what we found.

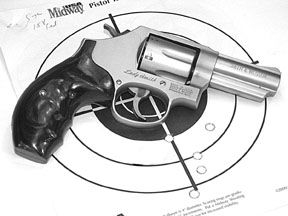

[PDFCAP(1)] Despite the designation, the Ladysmith is a traditional gun. Features that distinguish this model are a treated satin finish, fully shrouded ejector rod and rosewood grips. Beyond these features, the 65LS shares the short list of changes and improvements that Smith & Wesson has added to all its revolvers in recent years. The cylinder latch is relieved for speed loading. Just above it and nearly hidden is the internal hammer lock. Functionally, there is no perceivable change, but it does allow Smith & Wesson to continue making revolvers for all markets. Two keys are provided.

One other feature bolsters our argument that the 3-inch revolver is a better choice than a 2-inch model. The ejector rod on the 3-inch snubby is full length, offering sure ejection of the longer magnum cases. Though most snubbies are thought of as secondary or backup guns, the 3-inch model is easy to reload and its balance is quite favorable when using the two-hand reloading procedure. (See the accompanying reloading sidebar for details.) Using this technique, the chore of dumping empty cases and retrieving fresh ones is divided between both hands, saving time, but the method which keeps the gun in the strong hand requires the ejector rod to be pounded by the palm of the weak hand. In the event of difficulty extracting a spent shell, the weak hand can be injured. But even under normal circumstances this also means the ejector rod is prone to being bent. Since the tip of the ejector rod plays a part in lockup (there is no detent in the crane on this model) any slight misalignment will bind the action. A full-length ejector helps solve this.

As the 65LS came from the factory, we found that all fitting points, including the sideplate and lockup were well finished. The trigger was smooth and contoured. Even if you prefer a serrated or grooved trigger face, you want the edges to be smooth, and the 65LS offers this. Also, the edges of the trigger guard inside and out were gentle to our hands. We also liked the finish, which is not only glare resistant but also silky to the touch. The rosewood grip was a handsome match for this finish, but most people (especially ladies, ironically) will change this grip in favor of a more comfortable rubber model. Though this grip does a very good job of creating an effective palm swell free from any sharp edges, anyone using a high hold and magnum ammunition will pay an uncomfortable if not painful price. The rubber Bantam Grip from Hogue, which is currently found on most of Smith & Wesson’s round-butt models, is an ideal choice. The Bantam, like the supplied wood grip, also features finger grooves and an open back to shorten length of pull and make it more concealable. We spent a good deal of time at the range, and to be honest we replaced the wood grip with the most shock absorbing grip we could find in our box of miscellaneous grips. That was the Pachmayr Gripper ($18.31 from Natchez, 800-251-7839). If concealment and looks are not a major issue, why not opt for comfort?

The 65LS arrived in a padded, lockable presentation case. Though we don’t recommend it, we are sure that sooner or later someone is going to put this gun away in this case in a loaded condition. That causes a problem: The cutout inside that holds the gun is cut specifically for the supplied grip. To remove the gun from this case, one must put a finger or two either inside the trigger guard or in front of the muzzle. It just isn’t possible to leverage the tight-fitting gun out of place. An obvious relief in the form-fitting shell needs to be cut in such a way that any one removing the gun can do so without danger.

Our results at the range pointed out a specific characteristic of both our revolvers: Point of impact regarding elevation. The key to elevation in any gun with fixed sights is the height of the front blade. The front sight on this model was a serrated ramp, and it was one piece with the barrel. The rear sight was a notch in the top strap of the frame. We didn’t have any problem picking up a sight picture, but we found that the relation between the front and rear sights on this gun was suitable for only one weight bullet fired at high velocity. The only rounds that shot to point of aim were the full power 158-grain .357 magnum rounds. In practicing for our accuracy tests we fired a variety of rounds in both .38 Special and .357 Magnum. We fired double action only standing unsupported at 7 and 10 yards and save for the 158-grain ammunition, all the hits were low. Seated at the bench with targets 25 yards downrange, only one bullet and gun combination produced five-shot groups where they were intended to land. That was the Smith & Wesson 65LS firing Federal Hydra-Shok 158-grain jacketed hollowpoints. In fact the variation in group size was minimal at best. A Las Vegas bookmaker would feel safe betting on a 2.7-inch group at 25 yards with this gun and ammunition combination. Muzzle energy was impressive, registering an average of 529 foot-pounds from the 3-inch Smith & Wesson barrel. In terms of elevation our much slower moving 158-grain .38 Special round also shot lower, indicating the part that velocity plays in elevation. These rounds from MAGTECH featured the old-fashioned lead round nosed (actually pointed) slugs. Average groups measured over 3 inches in size, but these rounds were inexpensive and very easy to shoot. Our third choice of ammunition was one of our favorites.

[PDFCAP(2)]Winchester’s JHP Q4204 load is the .357 Magnum round for those who don’t like shooting .357 Magnum. The light payload of only 110 grains deducts much of the recoil associated with magnum ammunition but still produces over 380 foot-pounds of muzzle energy. Most revolvers that fire magnums as well as .38 Specials prefer the longer case. Time spent bouncing around inside the unrifled chamber can detract from the ability of the forcing cone to stabilize the slug, so accuracy may suffer. The Winchester 110-grain JHP produced the most accurate results of the test fired from the Ladysmith. A best group of only 1.7 inches resulted in an average 5-shot group of 2.2 inches. However, point of impact was as much as 6 inches low measured from point of aim to the center of the aforementioned 1.7-inch group. Since the front sight is part of the barrel and is not removable, we think most people will choose the round that best fits the gun rather than start filing down the front sight. A better solution is to remove the ramp completely and cut a dovetail into the barrel. That way any number of front sight blades can be applied. We have seen shorter-barreled revolvers equal or eclipse this performance, but they benefit from adjustable sights. The 2.5-inch-barreled Smith & Wesson 686 we tested in the April 1999 issue comes to mind, but that gun has suffered damage to the rear sight assembly on more than one occasion. So we prefer the integral combat sight. In choosing a Smith & Wesson 3-inch .357 Magnum, we suggest that it comes down to price and one single feature. If you don’t mind an exposed ejector rod, then you can save $50 by purchasing the 64.

[PDFCAP(3)] The 3-inch KGPF-331 demonstrates a different approach to building a revolver. The similarities to the Smith & Wesson products were in weight (within 2 ounces of each other) and stainless-steel construction. Both revolvers are sold as 3-inch models, but to be exact the barrel of the 65LS is 2.95 inches long and the Ruger’s barrel is 3.06 inches long. Each gun has a notch-in-frame rear sight and a ramped, serrated front sight. But, the Ruger’s front sight blade is pinned in place and finished in black. This could afford the Ruger more versatility regarding ammunition as it affects point of impact.

The top of the barrel was flattened and grooved to disperse glare. Both models rotate the cylinder in a counter-clockwise motion. Both the KGPF-331 and the 65LS shroud the ejector rod, and of course each gun offers single- and double-action fire.

From here we can point out a number of differences in design. The crown in the Ruger’s barrel is a cut recess. The ejector rod, though full length, does not take part in lockup. The cylinder latch operates by being pushed in, not slid forward as in the Smith & Wesson design. The Smith & Wesson extractor “star” is machined to act as one large gear, while the Ruger’s star relies on pins to connect with and turn the cylinder. The mainspring that drops the hammer on the Ruger is a coil design, which fooled us into thinking it is actually a leaf spring as found on the 65LS. It did this by not stacking or gaining resistance towards the end of the stroke. Usually this is a characteristic of coil-spring design.

To uncover the mainspring you remove a grip that is rubber with wood inlaid. Remove the grip screw that is countersunk to avoid contact with the palm, and then pull out the wood panels. Remove the aluminum keep that looks like a small barrel and the entire grip slides off the frame. Under the wood panels a small rod drops free. This is a disassembly pin to be used like a punch in taking apart the revolver. Overall, the Ruger grip is unique.

Though aftermarket replacement grips are available for the Ruger, we think the original equipment is as good as any of them. Even with the heaviest loads this grip did a very good job of letting us hang on and follow through with little or no discomfort. Our only complaint was that the edges of the trigger and surrounding trigger guard should be smoothed for comfort. We would also like to see this and other revolvers come from the factory with the chambers chamfered.

What do all these variations from Ruger to Smith & Wesson add up to? Single-action trigger pulls were identical at 6 pounds. Double-action triggers weighed in at 14 pounds for the Ruger and 12 pounds for the Ladysmith. Gunsmiths will likely tell you that each gun is a candidate for a trigger job. But keep in mind that anyone carrying a revolver with DA lighter than 9 or 10 pounds will likely need to handload special ammunition for the sake of reliability. In stock condition, we thought each gun’s trigger operated smoothly and predictably.

The Ruger KGPF-331 is longer than the 65LS, but it was also significantly lower in profile. However, the additional measurement was found in the height of the butt frame, so there is no advantage to be had such as getting the bore line deeper into the hand for better recoil control. The Ruger does not come with an internal lock but a cable lock is supplied.

In terms of accuracy the Ruger finished behind the Ladysmith. At close range standing, the difference was negligible, but at 25 yards from a sandbag the Ruger averaged 3.5 inches for all groups fired. The Smith & Wesson’s average group measured about three-quarters of an inch smaller. However, accuracy with the .38 Special MAGTECH ammunition was the same from both the Ruger and the Ladysmith. We think it is conceivable that a careful choice of ammunition for this gun would bring the Ruger very close to the accuracy displayed by the Smith & Wesson 65LS.

Other observations we were able to make about these revolvers included noise levels. In comparison with 2- and 2.5-inch models, the 3-inch models are quieter and muzzle flash is easier to ignore. Also, when drawing the gun for fire at very close range, in a “rock-back” drill for example, the 3-inch gun was only minimally slower than the shortest snubby. Yet, it was noticeably faster and easier to perform than with a 4-inch revolver. In our opinion the 3-inch barrel represents a true break point in the ability to perform fast handling techniques from either an exposed holster or from concealment. The 3-inch revolver is an excellent compromise.

Gun Tests Recommends

Smith & Wesson .357 Magnum 65LS Ladysmith, $584. Our Pick. Its accuracy was excellent, and it handled well.

Sturm, Ruger & Co., .357 Magnum KGPF-331, $529. Buy It. This is one of the more comfortable magnum revolvers to shoot, despite edges that can be easily contoured. We like the grip, the cylinder release and the sights. We think this firearm has additional potential in terms of accuracy.

Also With This Article

[PDFCAP(4)]