In 1959 Winchester unveiled its latest brainchild, the 22 WMR cartridge. The debut of the new rimfire excited shooters since it pushed a 40-grain bullet at a velocity of 2,000 fps. A similarly size 40-grain bullet from a 22 LR at the time had a velocity of about 1,200 fps. With more speed also came good accuracy. For larger varmints like fox, raccoon, and coyote, the 22 WMR was a good choice if used at short to medium range. Plus the 22 WMR had minimal recoil and cartridges cost less than any 22 centerfire ammo.

A few months after the cartridge debuted, Smith & Wesson had a revolver chambered for it and named it the Model 48. The transition to the new round was easy for S&W since they were already manufacturing the K-22 Masterpiece chambered in 22 Long Rifle. Colt was a little behind the curve, but it did chamber the round in fewer than 1,000 of the Officer’s Model Match revolvers and a very few Colt Diamondback revolvers. It wasn’t until the debut of the Trooper MK III that Colt took the cartridge more seriously.

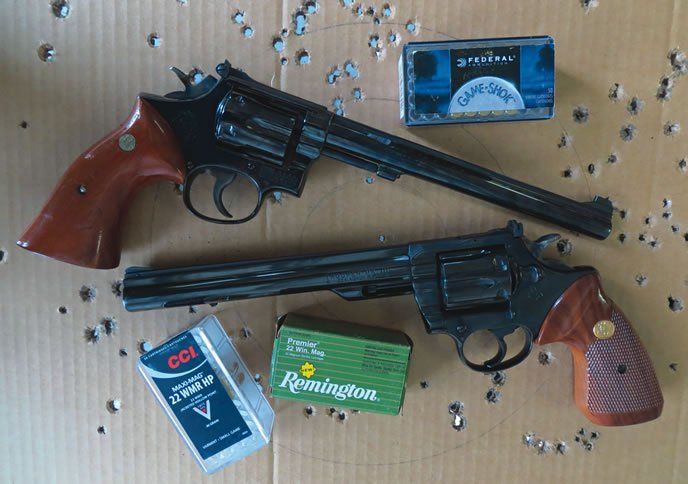

Many of our testers have experience with the round in rifles, revolvers, derringers and semi-automatic pistols. We wanted to determine what would be a good double-action revolver platform for the 22 WMR, and so we acquired two previously untested firearms, a S&W Model 48-2 and a Colt Trooper MK III, both with long 8-inch barrels. The S&W graded about 90-85% and the Colt 95-90%. These were two lovely blued revolvers with wood grips. They had obviously not been fired often, but we still went through our battery of pre-range testing of the cylinder-to-frame headspace, cylinder-to-barrel tolerance and the alignment of the chambers with the bore, using gauges from Brownells.com. All checked out fine, with the Model 48-2 cylinder gap measuring 0.002 inch and the Trooper MK III gap measuring 0.003 inch. There was no wiggle nor play in either cylinder, and they locked up tight. The screw heads on both guns also looked like they have not seen a screwdriver since the factory. These were sharp-looking revolvers in excellent condition. In doing research prior to the purchase, we collected prices for these firearms on the used market, and those price ranges are reflected in what dollar amounts we cite below:

Smith & Wesson Model 48-2 22 WMR, $900-$1300

In 1959 when the first Model 48s came off the production line in Massachusetts, they were available in three barrels lengths: 4, 6, and 8.375 inches. Since that introduction, there have been at least four model variants. The model variant is indicated by a dash and number, and this was a “-2” variant that began production in 1961, changing the cylinder stop and removing the fourth screw at the front of the trigger guard. The 48-2 variants were produced until 1967 when another design change was made. Today, under the Classic Series, S&W reproduces the Model 48 in 4- and 6-inch models. The Model 648 is the modern stainless variant.

The Model 48 uses S&W’s K-frame, which was one of S&W’s most important revolver innovations built specifically to handle the 38 Special cartridge. Since being introduced, the K-frame has been used in the Model 10, 17, and 19, chambered in 38 Special, 22 LR, and 357 Magnum, respectively. The frame allows for a slimmer revolver compared to S&W’s N-frames of the time.

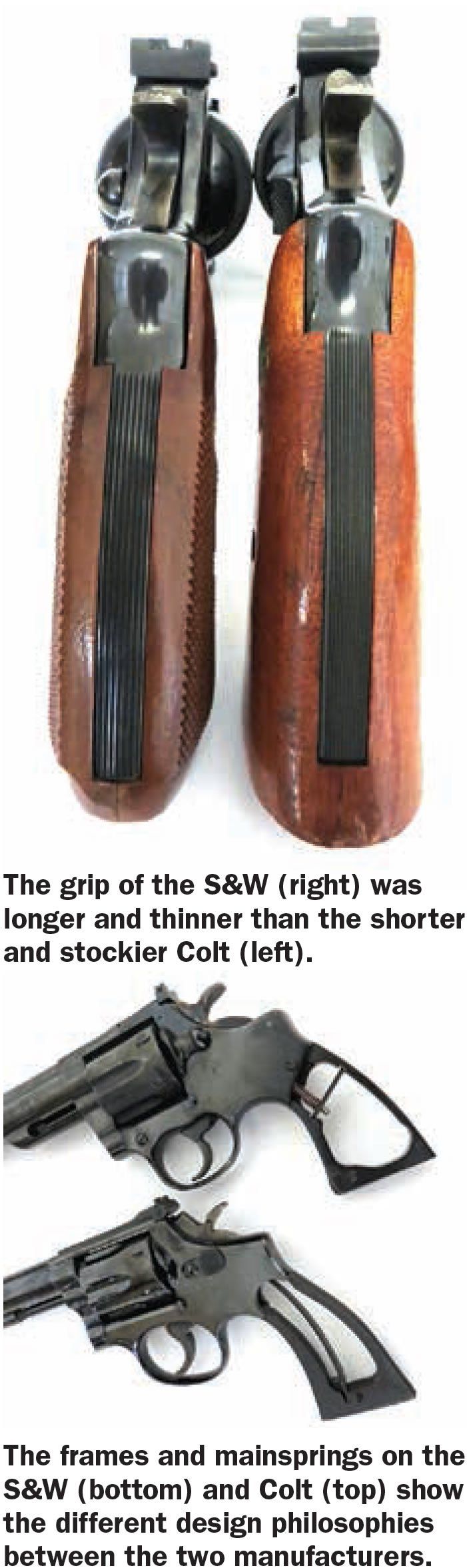

Our Model 48-2 featured a smooth magna-style wood grip with S&W medallion inset that gave the revolver a full feel in hand without feeling bulky. All testers liked this grip better than the Colt’s grip. Under the wood grip we found a flat main spring and a squared butt. Most, if not all, S&W revolvers built today have a round butt to reduce manufacturing costs. The rear backstrap was serrated for a surer grip. The finish was blued, and even for its age, was still nice with bluing only missing from some sharp edges. The barrel was a whopping 8.375 inches long, and even with the long barrel, the S&W had excellent balance, actually making it feel like the barrel was shorter. The top of the barrel was serrated, and the front sight consisted of a serrated ramp to a Patridge sight.

The rear was fully adjustable with a plain black notch. The rear of the sight was serrated to reduce sun glare. We liked the sights a lot, even though we have become accustomed to 3-dot and fiber-optic front sights. In the black of the target, the sights could get lost. Under the barrel was a partial lug that allowed the front of the ejector rod to lock into place.

The full spur hammer was checkered nicely and offered plenty of grip. And while the cylinder latch was the full-size old style, we liked the extra traction it provided, and it worked with precision. The ejector pushed empty cases free from the cylinder. The chambers in the cylinder were recessed so the base of the 22 WMR cartridges were flush with the rear of the cylinder. The wide trigger was designed for target work with fine serrations.

Getting to the trigger, we found a lot more to like in this S&W. The trigger pull seemed less in double action than what the scale measured at 10.2 pounds. We felt minimal stacking in double action and thought it was smooth. In single action, the trigger was fairly crisp, and we credit the trigger and grip to the small groups we were able to squeeze out of the S&W. With Federal Game-Shok 50-grain jacketed hollowpoints, we were able to get under half an inch for a 6-shot group at 15 yards. The Colt was a different story.

We were reminded that loading 22 WMR cartridges requires the rounds to be fully seated in the chamber. There is no gravity assist as with centerfire rounds. In use, the 48-2 was a fine revolver though testers thought the barrel was too long, making it a dedicated plinker as well as a small-game hunter. A full-size across-the-chest shoulder holster would be required to tote this revolver around with ease. Testers would more than likely opt for a 6-inch variant over the 8-inch variant. Though the longer barrel was helpful at longer distances — due to the longer sight radius and more barrel time to generate more velocity — we still would want a more manageably sized revolver. We doubt we would mount a scope or red dot on this revolver since we might reduce the value.

Our Team Said: The 48-2 was better balanced and more accurate than the Colt and it was less expensive than the Colt. A shorter 6-inch barrel would be more convenient than the 8.375-inch barrel.

Colt Trooper MK III 22 WMR, $900-$1500

The Colt Trooper MK III was introduced in 1969 to reduce the production cost of the previous Trooper model. Built on a new J-frame, the MK III was a modern step forward for Colt, using a transfer bar mechanism and coil main spring in lieu of the traditional flat-style spring. On introduction, it was offered in 4-, 6-, and 8-inch barrel variants in 22 LR, 22 WMR, 38 Special, and 357 Magnum. This model was produced until 1982. The 8-inch-barrel variant we tested sported a deep-blue finish that was spectacular and a checkered walnut grip with a gold Colt medallion inset. The steel frame was squared off, and the rear backstrap was serrated for a more positive grip. Removing the grips exposed the coiled main spring, which was a departure from Colt’s flat springs. On the top side of the barrel was a pinned ramped front sight. A previous owner painted the ramp green to better see the sight. Sights on both guns suffered when used on a black or dark surface targets. Tester also felt the Colt’s front sight was not as refined as the S&W’s Patridge. The MK III’s rear sight was fully adjustable and indicated to the shooter which way to turn the screw to increase or decrease elevation or windage. The S&W’s rear sight did not have indicators. Under the barrel was a half lug that encased the ejector rod.

Like the S&W, the Colt’s chambers were countersunk. It seemed more obvious with the Colt that these revolvers were re-engineered from a 38 Special/357 Magnum revolver down to a 22 rimfire since there was a lot of space between chambers, and the barrel of the Colt was designed for a 38 but drilled and reamed to 0.224 inch to accommodate the 22 WMR. This thicker barrel, combined with the 8-inch length, made the MK III muzzle heavy. Looking at the muzzle side by side, the S&W barrel looked like a skinny pencil compared to the stout barrel of the Colt. The grip was also an issue with some testers. It felt too short and too chunky compared to the S&W’s grip. The small grip and muzzle heavy balance were not a good combination.

The cylinder latch worked positively and the ejector fully shucked empties. The cylinder locked into the frame confidently. The hammer spur offered plenty of traction to cock the revolver. The trigger was smooth and felt comfortable, but during the double-action pull, we experienced stacking — so much so some testers did not want to shoot the revolver in DA mode, as the stacking affected aiming. The S&W definitely had a better trigger in DA. In single action, the Colt trigger was better, but still not as nice as the S&W.

The trigger, sights, and grip showed in accuracy testing. We tried to get a group under an inch using a rest, but could not, even with the three different ammo types and bullet weights. We expected more from the Colt.

Our Team Said: From the outset it was clear there were major differences between these seemingly similar revolvers. In the hand, the Colt felt muzzle heavy. We also thought its sights were less refined, and the trigger was not up to snuff. Many felt the Colt had a place in completing a collection, but the cost did not justify the purchasing the revolver for plinking or small-game hunting.

Special thanks toEastern Outfittersof Hampstead, North Carolina.

Written and photographed by Robert Sadowski, using evaluations fromGun Teststeam testers.