Wild Bill had a pair. Sam Bass used one, and so did Frank James and Cole Younger. Elmer Keith liked his very much. In fact, Elmer’s 1851 Navy Colt was one of his first handguns, and it undoubtedly influenced the grand old master all his life. We, too, like the Colt Navy, and so do many Cowboy Action shooters. With all this popularity we thought it would be a good idea to inform our readers where to go to get today’s best copy of the breed. Unfortunately, we can’t tell you that, because although we found an affordable fun gun, we haven’t found one yet that is thoroughly satisfactory.

It ought not to be all that hard to produce a decent copy of the Colt 1851 Navy, the popular octagon-barreled .36 percussion precursor to the famous Single Action Army Colt Model P of 1873. Today, when you can get really good copies of nearly any firearm ever made, we’ve yet to see a perfect job of copying the Colt Navy. Many factories or importers give us truly excellent clones of the Colt Model P, but they all fall a bit short in producing a good, modern 1851 Navy. We wonder why that is. This may sound like a simple gun to emulate, but apparently it is a problem for the several companies which still produce either the parts or whole guns today. In our testing of four examples, we’ve encountered rounded corners, wavy barrel flats, improper shapes and finishes to gun trigger guards, backstraps with the wrong configuration, soft parts, loading-lever latches that don’t work like they should, latch lugs loose in the barrel, failures of barrel wedges, and even one complete failure of a gun after only 36 shots.

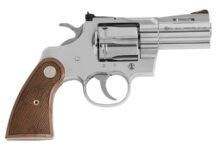

The Navy Colt, which got its name from the naval battle scene roll-engraved onto its cylinder, had a one-piece stock of walnut surrounded by a silver-plated brass grip strap and trigger guard. A notable exception was the London-made Navy, which had a blued iron guard and backstrap. The 1851 Navy Colt had a blued octagonal barrel of .36 caliber, and a color-case-hardened frame. It had a cone-shaped brass front sight and a notch in the hammer for the rear. Colt also produced many engraved presentation pieces with different finishes, but the most common Navy was as described.

We believe the makers today are trying to produce guns that are too inexpensive. If a shooter doesn’t balk at spending over $500 for a good clone of a SAA, why would he want a poorly made copy of a Navy? The least expensive of our test guns had a suggested retail of $119, and at that price you can’t expect a world-beater. However, this gun at least shot, and was lots of fun. We remember a man and his son some years ago trying to make a poor-quality percussion revolver work, but the gun was so badly made they couldn’t even make it fire. This didn’t do anything for the youngster’s enjoyment or confidence, and totally spoiled the day for both father and son.

The grips of both the original 1851 Navy and original Colt SAA are essentially the same size and shape. Many gun makers produce excellent copies of the SAA, so you would think it would not be a big deal to produce the identical grip, in either steel or brass, for an 1851 Navy revolver. You would be wrong.

The sides of octagonal barrels are supposed to be completely and absolutely flat, and the corners should be sharp. Not one of the guns offered this, and the most expensive was the worst offender.

The Guns

We tested four copies of the Navy, two of them supposed “London” models. The guns were the $120 Cabela’s 1851 Navy (made by Pietta in Italy), the $400 Colt BP Signature Series London Model (assembled by Colt BP in New York from Armi San Marco parts), Cimarron’s $259 London Navy (by Uberti of Italy), and EMF’s $135 version (made by Armi San Marco). The weights of all four guns were within 1.5 ounces of each other.

We first disassembled each gun into its three major components by pulling its barrel pin, removing the barrel assembly, and taking the cylinder off the base pin. We then cleaned out all the oil from the chambers and wiped the gun all over with solvent, and then rubbed the entire gun, inside and out, with Ox-Yoke Originals’ Wonder Lube 1000 Plus, a black-powder lubrication that in our experience has proven to be a superior product for all muzzle-loading firearms. It gives easy cleanup and fine protection for all parts of all muzzleloaders. We greased the base pins with Lubriplate, then assembled the guns for our shooting and evaluation.

Loading

The usual recommended method of loading percussion revolvers today makes for a big mess, and is entirely unnecessary. It consists in seating the balls firmly over the powder charge, then filling the remaining space with grease to prevent cross-firing. The grease attracts all manner of dirt. If the powder charge is light, there’s up to half an inch of grease within each chamber, and if the gun gets hot that grease will run out, creating an even bigger mess.

Long ago Elmer Keith wrote up the correct method of loading cap-and-ball revolvers in his book “Sixguns,” and we adapted his method using modern and very effective components. We used only GOEX FFFg black powder in 15-, 20-, and 25-grain loads. We covered the powder with a pre-lubricated No. 3600 Ox-Yoke Wonder Wad, then rammed the ball down tightly on top of that. We used NO grease over the ball. We’ve loaded all of our personal collection of original and 2nd Generation Colt percussion revolvers that way for many years, and can shoot as long as we like with no tying-up of the gun from fouling, no leading, easy clean-up, and excellent overall results. Accuracy is generally improved with the Ox-Yoke wads, too.

We used CCI brand number 11 percussion caps with all loads. They worked well and gave a proper fit. Note that a loose cap can recoil back against the recoil shield and detonate, and that is probably one common cause of “cross-firing.” If the cap is too tight it won’t go on all the way and the cylinder won’t turn. We used Speer swaged lead balls of 0.375-inch diameter.

By the end of our testing we much preferred the 20-grain load as our standard. It gave enough room in all the guns for the Ox-Yoke wad and the ball with a little room to spare for clearance. It shot well in all the guns. We tried lighter and heavier loads, but shooting was erratic. We tried a load as light as 10 grains, but there was too much room left over in the cylinder, and because black powder requires a compressed charge for proper burning, we had to stack the Wonder Wads sometimes three deep to get compression. Grouping was poor, so we quit that light load.

[PDFCAP(1)].We didn’t try conical bullets because they have to be cast, and that induces another variable. Swaged lead balls generally give better accuracy, are easy to load, inexpensive, and from what we’ve read they performed better in service. Most shooters, we feel, will go this route also.

All our test shooting was done at 15 yards. All the manufacturers recommended loading only five chambers, but we loaded all six for our testing, and fired the gun immediately. Original Colts had a pin between each cylinder that fit into a notch on the hammer, so the guns could be carried fully loaded in relative safety. Cabela’s and EMF’s guns didn’t have safety pins; Cimarron’s and Colt’s did.

Of our test guns only Cabela’s version was worth the money. It offered lots of fun, looked almost right, and didn’t break the bank. The Cimarron broke, but we liked it enough to buy it, fix it with trepidation, and hope it would last. We’d have a hard time buying the EMF because it didn’t work with the screws tight, and it would need fixing right out of the box. Yet it shot very well, and if you can manage to get it tinkered into the right condition it would be worth the effort because of its shooting qualities and good looks. We can’t recommend buying the Colt BP gun, not with that poor metal work on it.

More details on the guns follow:

Cabela’s 1851 Navy

Our recommendation: For $119 one ought not to expect too much, and with that in mind the shooter may find this gun will provide all the fun he wants. The gun was tight, shot well but high, and went bang every time. We liked this one a lot, especially when factoring in its affordable price.

The Cabela’s Navy was made by Pietta and imported from Italy. The unplated brass grips were at the wrong grip angle. Every person who grasped this handgun said it pointed too high, and the grip didn’t feel right. The barrel flats, and all the metal-to-metal work, were not as well done as on the Cimarron, but far better than that on the Colt BP, in our estimation. There were no hog wallows between the sides of the nicely case-colored frame and the trigger guard or back strap. However, there was some pronounced waviness on the left side of the frame and trigger guard.

The roll-engraved battle scene was very lightly impressed, and buffed to non-existence at the front edge of the cylinder. The hammer had serrations, not the correct checkering on its gripping surface. This gun alone of our test examples had a loading lever that latched correctly, snapping easily back into its notch under the muzzle with finger pressure. None of the other test guns worked this way, requiring a rearward pull on the latch itself to put the lever back into place. Little things like this make a big difference in a day’s shooting.

When we attempted to disassemble Cabela’s 1851 prior to shooting, we were unable to get the barrel wedge out without resorting to a hammer. The wedge was too tight in its fit in the frame and cylinder base pin. Also, the barrel wedge came apart when we took it out. We put it together and it stayed that way for the remainder of our testing.

With the hammer of the Pietta/Cabela’s gun at full cock, there was very little rotary movement to the cylinder. All the other test guns had varying amounts of slop, indicating their chambers were not lined up perfectly with their barrels. This causes poor accuracy and accelerated wear. By comparison, three genuine old Colt Navies we examined had less cylinder shake than three of our test guns, so this was a feather in the Pietta/Cabela’s hat.

This gun shot high, though it shot quite well. Average groups with all loads were 2.5 inches. The best group we fired (with 25 grains of FFFg) put five of six into 1.25 inches, but one shot expanded the group to 3.25 inches. We suspect a bad chamber, because we often got five shots into a tight group with one wide flyer. In fact, four groups averaged 1.4 inches for five of the six shots. Barrel roughness caused some leading. This gun shot more than well enough to give the shooter lots of fun for his money, though most groups were 4 to 6 inches higher than the point of aim.

Colt BP 1851 London Signature Series

Our recommendation: For $399 you ought to get a well-made, nicely fitted and finished handgun that shoots accurately. The Colt doesn’t offer anything but great bluing and case coloring on poorly finished metal. We don’t believe the price is justified, and don’t recommend it.

The overall appearance of the Colt is outstanding, until you look closely. The bluing, color case hardening, and silver plating on the Colt BP London gun were very nicely done. The color case-hardening was eye-catching and radiant, an excellent and vivid example of that finish. Sadly, the metalwork underneath was offensive. This gun was so poorly polished and fitted that the gun appeared to have been reblued. The metal-to-metal joints were very poorly done, the sides of the frame had deep depressions at the screw holes, and the “flats” of the barrel were actually rounded on top. The barrel sides were buffed to a nice gloss, but the barrel was buffed so much you could barely feel the corners with your thumb. The frame and barrel were buffed all around their edges before they were finished, and the joints where they met any other parts were rounded and poorly fitted. This is nothing but poor quality work, in fact some of the worst metal fitting we’ve seen. The makers need to examine a good-condition original to see what they’re supposed to look like, and then duplicate that look on the Colt Signature Series.

The Colt was very hard to cock when we got it. On close inspection, the rear of the barrel was not parallel to the front of the cylinder. The bottom of the barrel at the throat rubbed on the front of the cylinder, and the cylinder-to-barrel gap was notably tapered toward the top. To fix this we had to stone the rear of the barrel at the bottom, to make it possible to easily cock the gun for our test shooting.

The rounded trigger guard of this “London” model is a vast improvement over the tiny square-back guard of the standard Colt BP Navy. We can do without the signature of Sam Colt on the backstrap, but some like it, and it’s not offensive. The silver plating on the brass is very well done, and is an entirely correct finish. With time the silver will blacken, and that can make the gun look better. If the metal polishing were up to snuff, we’d like this gun a hundred times more.

The one-piece hardwood grips were well fitted and nicely finished. The gun felt absolutely right. The balance, trigger, and even the action—once we freed the cylinder from the barrel—felt really good. Across the room, the Colt BP looked great. The inside of the barrel appeared to have good and prominent rifling, but there was some roughness that contributed to leading and poor accuracy, in spite of our efforts to keep it clean. The average six-shot group with our 20-grain load was 3 inches. The smallest group, fired through an immaculate bore, was 1.5 inches. Alas, the next group was 2.6 inches. With the 15-grain load and double Ox-Yoke wads we managed only 2.6-inch average groups, and the barrel continued to collect lead.

Cimarron London Navy

Our recommendation: This $259 gun really caught our attention. A London Navy copy! The correct iron strap and guard! Add to that a nicely finished barrel with sharp corners, a great-feeling action, and you’ve got a gun that impressed us. Then the darned thing broke after 36 shots.

We thought we had a winner, so imagine our grievous disappointment when, with no warning, the cylinder bolt would no longer stay down with the gun on half-cock. The bolt would slip off the hammer lug prematurely, making it impossible to turn the cylinder with the hammer on half-cock. That means we couldn’t load the gun, and our initial favorite had become worthless. The erratic bolt caused a score-line around the cylinder, ruining the finish.

However, we liked this gun so much we looked hard for a solution. We thought the cause of the failure was due to an investment-cast hammer that had a rounded-off bolt-stop cam pin, permitting the bolt stop to slide off it at half-cock. We obtained a new hammer from the factory but it didn’t fix the problem. We finally took a chance on breaking a part, and bent one arm of the bolt so that its two legs splayed outward. That fix lasted throughout our testing.

On the plus side, this gun looked very good and it felt crisp. Cimarron got the steel backstrap too long, but the company got the trigger-guard shape just right, big and rounded, like they were on original London-made Navies. The Cimarron’s case coloring was a bit spotted on the right side, and nowhere brilliant, but it was entirely adequate. The bluing was very good, though the cylinder scene was a bit too deeply impressed. The well-finished wood stocks were not a perfect fit but adequate. The metal-to-metal fitting was well done, and the overall look was satisfying.

The loading lever didn’t latch easily, so we fixed it. We removed nearly one-eighth inch from the squared edge of the lug, plus some from the end of the loading lever latch. Then we could close the latch by finger pressure, like you could on original Colts. The latch lug was loose, and we took it out of its dovetail slot with our fingers. We staked it back into place so we could proceed with our testing without fear of losing it.

When we took the gun apart to fix it, the hammer screw was already showing wear, indicating it wasn’t hard enough. We polished, hardened, and tempered it to try to stop the wear. We encountered no further evidence of wear on the hammer screw by the end of our testing, proving that the part was too soft originally. Black-powder guns create lots of abrasive grit, and all the gun’s parts have to be able to take it. The Cimarron London Navy shot well enough. Lockup of the cylinder was good but not as tight as the Cabela’s gun. We often had five shots in a tight group with one wide flyer, and sometimes four in one group with two flyers. The gun shot close to where it looked. The average group size with the 20-grain load was a satisfying 2.1 inches. For comparison’s sake, with grease over the ball and no Ox-Yoke wad, a load of 20 grains averaged just over 3 inches.

EMF 1851 Navy

Our recommendation: For a retail price of $135, the EMF looked pretty good, but the screws were loose when we got it. When we tightened all the screws, the hammer locked up, so we loosened them again. The gun shoots well but needs good nipples. This one looked much like the real thing. The brass wasn’t silver plated, but the barrel sides and all the metal-to-metal fitting were quite good. The bluing was well done, and the case colors were muted and dark, but rich looking. The barrel flats were pretty doggoned flat, and we had to look hard to find any waviness. We judged the metalwork to be acceptable. This gun alone of the test guns had a trigger guard and backstrap profile that was close to correct, being large and with slightly squared-off corners. At arm’s length we couldn’t fault it, other than the missing silver plate.

We discovered the loading lever latch lug was dovetailed at an angle, and it came loose with a slight tap. However, it never fell out of the gun during our shooting. The lever could not be latched by hand pressure. The one-piece stock was well fitted and finished. Lockup was anything but tight, but the gun shot well enough.

The gun was somewhat hard to cock, but so were originals. There was some creep to the trigger, but the pull was acceptable. In fact, all our test guns had more-than-decent trigger pulls. The cylinder battle scene of the EMF Navy was illegible in some places, and very faint throughout, with some details missing. The cylinder openings were slightly rounded at the front, but this didn’t ease loading. In fact, we found this gun didn’t accept the balls very readily.

There were problems with some of the nipples in that we often had to give the cap two strikes of the hammer. We’d replace the nipples- on all the test guns-with Uncle Mike’s stainless nipples if the guns were ours. Our best group with the EMF had six in 1.4 inches. The gun shot fairly close to its sights with our 20-grain load, giving average groups of 2 inches. For two strings we made a composite target that had 11 of 12 shots in a group that measured 1.7 inches center to center of the widest shots.

Gun Tests Recommends

We wanted the word of an expert on today’s Colt Navies to see if we’d overlooked anything in our test. We spoke with Kenny Howell, head man at R&D Gunshop in Beloit, Wisconsin. Howell made the guns for the character Jim West in the current movie, Wild, Wild West, and last year R&D Gunshop made more than 1,200 cartridge conversions of percussion handguns for Cowboy Action shooters. We thought if anyone would know where to get a really good Navy Colt, Howell would.

Howell told us what we didn’t want to hear. In his opinion, no one makes a good Navy today. He used to spend about 10 hours fully converting a 2nd Generation Colt 1851 Navy. Today his time to convert a Signature Series Colt is nearly twice that. He has to rebuild much of the existing gun. He rehardens many parts, draw-files the barrels, drills and replaces the bolt cam in the hammer, rehardens the hammer, and performs other work. He told us he would much rather work on 2nd Generation Colts or originals than on any of today’s copies. He told us the Wild, Wild West guns were a major chore to rebuild.

Disappointed, we looked at our test quartet with the knowledge that there was no dark horse product out there that might surpass them, and took that into consideration in making our evaluations:

Cabela’s 1851 Navy by Pietta, $119. This gun will give the shooter a decent taste of history. We were unable to break the gun during our limited shooting, and as well fitted as it was it ought to last a long time. It would be our first choice for value received and for cheap fun.

Colt BP 1851 London Signature Series, $399. We loved the arm’s-length appearance of the Colt BP Navy but would never spend $399 for it. We don’t like inappropriately rounded-off edges. If Colt BP can polish the metal correctly (without increasing the price), the company would have a much better gun. There are the makings of one of the best possible Navies here, but at this point, they come up short. We wouldn’t buy this gun.

Cimarron London Navy, $259. We liked this gun better than the Colt BP and EMF in spite of its early failure. Our simple fix lasted throughout our testing, and we purposely cycled the hammer many times in a vain attempt to make it fail. We’d buy it, but would expect to spend additional money for occasional repairs.

EMF 1851 Navy, $135. We didn’t like the fact that this gun was rendered non-functional by the tightening of the hammer- and backstrap screws. That indicated a lack of care in its assembly, in our judgment. This gun needed detailed attention to make it fully reliable. However, for the price it was a lot of fun, quite accurate, and it looked closest to the real thing.

We think that if someone made a really high-quality copy of a Navy— all sharp edges, correct profiles, parts properly heat-treated to last forever, good fit and finish—and sold it for around $400 to $500, they’d sell a lot of guns. However, we have no idea how large the market is. Surely some Cowboy Action shooters want reliable, well-made percussion revolvers and would be willing to pay a fair price for top quality. We’d rather spend $2,500 for the real thing than $250 for something that just isn’t right—and there’s a lot not right in the current crop of Navies.