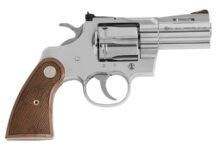

Best in Class: REVOLVERS

Ruger GP100 .357 Magnum

No. KGP-141, $615

Reviewed: August 2006

Ruger lists seven different models in the GP100 family with barrel lengths of 3, 4, and 6 inches. Finishes are either blued or stainless steel. Manufacturer’s suggested retail prices range from $552 for the .38 Special +P only models to $615 for the stainless steel .357 Magnum revolvers with barrel lengths of either 4 or 6 inches. All models come with a rubber grip complete with a rosewood insert. Our 4-inch barreled KGP-141 had a pleasing bright-stainless finish and an adjustable rear sight. Elevation was the familiar clockwise for down and counter clockwise for raising the point of impact. The windage adjustment required opposite movement for changing point of impact.

A second, very small screwdriver was required to turn the windage-adjustment screw. The rear-sight blade was partially protected from impact by riding back and forth inside the body of the unit. The rear notch was accented with white trim. The front sight on our Ruger was a black ramp grooved to reduce glare and dovetailed into place.

This is not the only feature on the Ruger revolver that distinguished it. The top of the barrel shroud was flat and grooved. The shooter pressed the cylinder release rather than slid it forward. The full-length ejector rod played no part in lockup, but a heavy detent mounted on the forward surface of the crane meshed with the frame. The Ruger featured a full-length underlug and overall gave the impression of being overbuilt. The cylinder lugs, for example, were deeper and wider than those found on other guns.

The grip was in fact a rubber sleeve that covered the butt frame that also housed the coil mainspring. It was held in place by a barrel-shaped lug captured by the rosewood inserts. The inserts had to be removed from each side and the lug pushed through before the rubber portion of the grip could be slid off of the frame.

The Ruger mixed squared edges, such as at the trigger and the hammer, with graceful sweeping lines on the barrel and behind the cylinder. The Ruger revolver did not offer an internal safety lock. A padlock designed to pass through a single chamber with the cylinder swung away from the frame was supplied.

The trigger on our KGP-141 revolver had a smooth single action with a pronounced let off. The Ruger double action was smooth from start to finish, with the same felt resistance each time. Starting and stopping the cylinder produced little interference. This was followed by the smallest touch of stacking, which indicated the coil mainspring was fully loaded.

Our shots fired double action formed the best group at center mass in our rapid-fire test. Four out of five shots to the head area formed the tightest group as well. From the bench our single-action-only shots averaged 1.7 inches firing both the hottest loads (the 125-grain magnums) and lightest, the Black Hills Match Wadcutters. But even in the case of firing the 158-grain .357 Magnum JSP loads, the difference between smallest and largest group was very narrow.

Given the fact that our accuracy test was performed under overcast skies with light rain, we were pleased with the sights on the Ruger revolver. Due to the clear, rugged design of the sights combined with the consistency of the trigger, in both single and double action, we never lacked confidence firing the Ruger GP100 revolver.

REVOLVERS RUNNERS-UP

Heritage Manufacturing

Big Bore Rough Rider

.45 Colt RR45B5, $379

Reviewed: February 2006

According to a number of online dictionaries, there is no definition listed for the term, “cowboy gun.” Nevertheless, the popularity of revolvers descending from the Colt Single Action Army has brought new meaning to these words. Since 1999 we have tested at least 18 different handguns that fit what we define as a cowboy gun. One is the Heritage Manufacturing Big Bore Rough Rider No. RR45B5, $379, a six-shot single-action revolver with 5.5-inch barrel and chambered for 45 Colt.

The Rough Rider was dark-blued steel with a tall front sight and a rear sighting notch exposed when the hammer is pulled back. The cylinder rotated clockwise, and with the loading gate open, the cylinder clicked with the indexing of each chamber. Ejector-rod movement was approximately 2.7 inches. The hammer lacked a firing pin, using instead a transfer-bar system for greater safety. The grip on the Rough Rider was wood. The shape of the bell-shaped grips each started with a wide base that tapered to a 4.1-inch neck.

Our test distance was 25 yards from a sandbag rest with four different choices of ammunition, two modern and two others sold in boxes decorated with Old West graphics. The modern rounds were Winchester’s 225-grain Silvertip hollowpoints and Remington’s 225-grain lead semi-wadcutters. The remaining ammunition brands, likely being marketed to Cowboy Action shooters, were 250-grain lead flat-point rounds from PMC and Black Hills Ammunition.

The Rough Rider RR45B5 belongs to the Big Bore series from this Opa Locka, Florida-based corporation. Unlike the company’s rimfire models, the components of the Big Bore guns are manufactured by Pietta of Italy and assembled by Heritage Manufacturing here in the states. Available finishes are blue, case hardened, and stainless steel. Available barrel lengths range from 4.75 inches to 7.5 inches. The MSRP on each gun, whether chambered for .45 Colt, .357 Magnum or .44-40, was the same. The Big Bore models, which are centerfire guns, differed from the Heritage rimfire models by not including their unique frame-mounted thumb safety.

Loading and ejecting rounds was flawless. Removing the base pin to extricate the cylinder was simple enough, but also a little sticky, too. The inertial firing pin on the Rough Rider was held inside the frame by a bushing that was visible with the hammer pulled back. The rear notch of the Rough Rider was clearly defined and the front blade was squared off, making the desired sight picture easier to discern.

At the range we learned that the Remington rounds packed the most power, producing almost 400 foot-pounds of muzzle energy when fired from the Heritage Manufacturing revolver. The 250-grain lead flat-point rounds from PMC and Black Hills Ammunition lagged considerably in this department, but this was not a surprise. What was surprising was the difference in velocity (and power). In all four cases the Rough Rider pushed its slugs much faster than did other test guns. The average difference for the Winchester and Remington rounds fired from the Rough Rider was an additional 128 fps on average.

The Rough Rider shot to point-of-aim with the 225 grain rounds and just a little higher than our 6 o’clock hold when we fired the 250-grain rounds. The best single groups were achieved with the Black Hills and PMC 250-grain rounds, (1.3 and 1.4 inches respectively), but the Winchester Silvertip HP rounds were right behind, (1.6 inches). In fact, all but the Remington rounds helped us achieve an average group measuring 2 inches or less.

Taurus Mod. 94B2UL Ultra-Lite

Nine .22 LR, $375 MSRP

Reviewed: March 2006

Something about this Taurus gave us confidence. It might have been the weight, maybe the nicely blued finish, but probably it was the excellent-looking adjustable sights, with a bright red insert in the flat-top front post, and the white outline, square-notch rear, just the sort of thing you’d expect. Our inspection quickly showed the gun to be tightly fitted. Its nine-shot cylinder swung out positively, and locked back up tightly thanks to a sprung latch pin in the crane that snapped into a cut in the frame. The main lockup was at the rear of the cylinder using a central sprung pin. It weighed 18.2 ounces, contradicting the meaning of the “Ultra-Lite” designation. The Taurus’s grip wrapped around the back, giving a hand-filling feel.

We noticed the ejector rod did not give a long-enough stroke to clear rimfire cases completely, lacking an eighth of an inch or so from coming clean, but this didn’t prove to be a big problem. The frame of the Taurus was aluminum alloy. The cylinder, barrel, crane, sights, hammer and trigger were all steel, hence the added weight. The hammer was short but wide, making it relatively easy to cock, but we noticed the hammer spring felt inordinately strong. Of course we had no misfires, but if that spring were slightly less powerful we suspect the DA pull would be far more useful. The SA pull was 5.2 pounds; the DA pull was about 14 pounds.

Fit and finish were generally excellent, but we found a nasty burr around the rear of the barrel inside the frame, and another on the outer edges of the barrel at the muzzle. This latter appeared to be a burr that was overlooked after the muzzle crown was cut. Cleaning it up would be mandatory to avoid cut fingers.

Our first impression at the range was joy in that we could see the front sight. But after a few shots we wanted more space on the sides of it, which would require a wider rear notch. That would be easy to get with a small file. We found the red-insert front blade stood out well against trees, black targets, and snow. We tried blackening it but didn’t like that as well. Five CCI CB caps, offhand from 6 yards, gave four shots in half an inch, and all five in 1.1 inches. We were not surprised. At 15 yards, the Taurus performed as expected. The first group fired (Winchester) was 1.8 inches, and the second had four shots in 0.7 inches. At this point we knew we had a winner in the Taurus.

Ruger Super Redhawk Alaskan

No. KSRH 2454,

.454Casull/.45 Colt, $860

Reviewed: March 2006

When we first heard of the Alaskan, we thought it might be similar to a package modification available from Cylinder & Slide (). This package started with shortening the barrel of a Super Redhawk to create a snub-nosed revolver. The Alaskan, with its 2.5-inch barrel, is indeed a snubby. But unlike the standard Super Redhawk, where the frame and barrel are two units, the Alaskan’s barrel shroud and frame are one piece. This is unique among the Ruger revolvers, and we can’t recall seeing similar construction elsewhere. Another first for the Ruger revolvers is the use of a rubber Hogue Monogrip. More often found on Smith & Wesson products, this was a one-piece grip, devoid of separate panels, that slides on from the bottom of the frame and connects by a yoke applied to the butt end of the frame. It features a pebbled texture, finger grooves and a palm swell on both sides.

The Ruger Alaskan is one of the sturdiest and most impressive looking production guns we have seen. In contrast with the black rubber grip (and the sights), the entire gun is stainless steel with a brushed, shiny finish. The finish looked easy to keep, but we have not been able to remove stains on the underlug beneath the muzzle. Machine polishing may be the only answer.

The sights on the Ruger Alaskan consisted of a black ramp with cross serrations at the front and a fully adjustable unit to the rear with a white outline surrounding the notch. Despite the top strap being shiny and wide, we didn’t suffer from glare when we aimed. The sight picture was easy to read. The cylinder rode on a crane that was locked by a detent inside the frame. The ejector rod did not play a part in lockup but was fully shrouded beneath the barrel.

The trigger on the Ruger weighed in at about 15 pounds double action and 6 pounds single action. The single-action stroke at times displayed a small measure of creep.

Snubbies are never the best fit for a bench rest, but we still managed to shoot an average size group of 2.3 inches with all three of the standard pressure .45 Colt rounds. One characteristic of the Ruger was that before changing from firing a lead bullet to a jacketed round, the cylinders had to be cleaned. Otherwise groups became erratic. The Alaskan produced more power than other test guns, and we checked velocities twice, making sure that a dirty cylinder was not adding pressure. The Speer rounds were simply better suited to the Ruger. But the real stars of the test were the 328-grain rounds especially loaded for Ruger revolvers and Thompson Center single shot handguns. Firing the Ruger Super Redhawk Alaskan stoked with the 328-grain rounds was similar in feel to .44 Magnum but without the same blast or flame. Velocity averaged 1024 fps, producing a whopping 764 foot-pounds of muzzle energy.

Still, controlling the Alaskan with these loads was not difficult. The Hogue grip allowed us to get a high hold on the gun, and its profile helped us index straight up and down without the gun swimming out of our grasp. Groups from the bench ranged from 2.1 inches to 2.8 inches for an average of 2.5 inches overall. In terms of rapid fire, when firing the 328-grain loads, we doubt we could have fired the Alaskan any faster than the time it took for the sights to return after each shot.