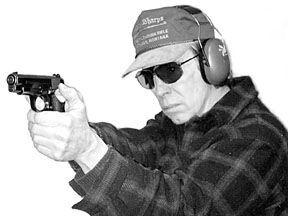

We take a look here at two more surplus mid-caliber and mid-size semiautomatic pistols. They are of mixed action types, one single action and the other, double action. The Spanish Star S.A. was a single-action 9mm that closely resembled a slightly shrunken 1911 without beavertail or Commander-style hammer. It also lacked the 1911’s grip safety, but was a reasonably hand-filling autoloader. The second gun was a lighter and slightly smaller Makarov P-64 in 9×18 that looked superficially like a Walther PPK. It had the same takedown procedure as the PPK, but its hammer was sunken into the rear of the slide so deep as to defy hand cocking. However, its double-action feature was supposed to make hand cocking superfluous. The prices were reasonable enough to catch our interest, and the guns had similar potential uses, so we gave them a good, hard look. Here’s what we found.

[PDFCAP(1)]Star’s all-steel 9mm hasn’t been on the market in nearly a decade, but Southern Ohio Gun came up with a bunch of ‘em that are priced right. Our 4-inch-barreled sample was in very good to excellent condition. It was fitted with checkered black-plastic grip panels that fit it well. The gun’s grip size and shape were close in feel to the 1911-A1 contour, with a slight bulge in the lower portion of the back strap and a slight flare to the bottom of the front strap. There was no grip safety, but we found that the magazine had to be in place in order to drop the hammer. Some (including most of us) consider that to be a tactical blunder, because if you need to shoot in the middle of a reload, you’re out of luck.

The gun was not new, but surely not abused. It retained about 98 percent of its bluing, and there were no major mars to it. The slide was nicely flat on its sides, with an attractive matte finish beneath its bluing. One noticeable purple blemish, which may have been an annealing mark, was on the left side of the slide. A tiny stress-relieving hole had been drilled in the corner of the notch where the slide-stop caught the slide. The purple spot surrounded the tiny hole. The slide was not all that tight on the frame, so we had no illusions of match-grade accuracy with this handgun. The top of the slide had two longitudinal grooves about half an inch apart, apparently for decoration. They vaguely resembled the grooves for a .22 tip-off mount. It would have been natural for the slide top to be roughened between the grooves to eliminate glare, but that was not done. The fixed sights gave an excellent Patridge-like sight picture, though we could have used more room on the sides of the rear notch. This would have made it easier and faster to pick up the front sight. The rear was adjustable for windage by drifting in its dovetail. The front sight blade was integral with the slide. The rear sight, as it was, would cut the hand badly during a clearing drill, but some careful work with a file would help that.

Takedown was really slick. You cleared the gun and removed the magazine, then pulled the slide back until you could slip the safety into a notch on the side of the slide. Then the barrel pin, which was also the slide release lever — like on a 1911— could be pressed out. Then, as you hold the slide to keep it from flying forward, simply press down on the safety lever, and the slide can be eased off the front. The slide spring remains captive on its pin, and this assembly may then be lifted out of the slide. The barrel can be removed from the slide (toward the front) after rotating the front collar, just like on a 1911. Reassembly is just as easy. This setup is much easier than taking down a 1911-type auto.

Inner workmanship was excellent. The barrel locked to the slide in a manner identical with the 1911, via a bottom link pin and a single upper lug that fit into the slide. This gun was well thought out and well executed. The ONLY thing we didn’t like was the mag safety, and though it looked easy to deactivate, that’s probably a bad idea if you plan to carry the gun for self-defense, from a legal standpoint. The magazine well was slightly beveled on bottom to permit faster reloads. That means you’ll have to scare up spare magazines, because only one comes with this excellent gun.

The slide-spring rod protruded from the front as the slide moved rearward. Press-checking by the old method was therefore out of the question. The extractor was similar to that of the new SW1911. The long hammer spur looked like it would bite, but inspection found that it could not. The hammer, which was easily hand cocked and uncocked, encountered a stop before it could pinch the web of the hand against the stubby frame extension. We applauded the absence of a grip safety, but as noted, deplored the magazine safety. We found the magazine would not drop free from the gun by simply depressing its 1911-like button release. The magazine had to be pulled from the gun, a definite detriment to efficient gun handling. We found this was because of the magazine safety, which dragged on the magazine. The slide stop would permit fast closing of the slide on a fresh magazine, if you shot the gun until it ran dry. The magazine could be disassembled with ease for cleaning. The magazine held eight rounds in a single-column stack. The mag was easy to load, and gave visual evidence of the remaining rounds through slots in its right side.

The trigger was long enough for our fingers and had an outstanding pull, giving a clean break at just over 3.5 pounds. The first stage of the two-stage pull required about 2 pounds. The thumb safety operated like that of a good 1911, going on with a bit of a push and coming off easily with moderate thumb pressure. We could ride our thumb on the safety during firing, though some might like a longer safety lever for more comfort. The slide had sharp, effective cocking serrations that gave good control. This was a well-thought-out and well-executed pistol that all our shooters liked. It performed well enough with the right ammo and had no problems whatsoever. One thing to avoid, we found, was to rest the trigger finger on that long slide-stop pin while cranking in a round. The pin can fly out with great ease, giving you a loaded, partially disassembled gun.

[PDFCAP(2)]

Our first action with this gun was to disassemble it to wipe off massive amounts of packing oil (that looked and smelled like cooking oil) from all the parts of the gun. Disassembly was not as easy as with the Walther PPK, which this gun vaguely resembled. Disassembly was essentially the same as with the PPK, but we felt it should have been easier to accomplish. After clearing the gun and removing the magazine, we pulled the trigger guard downward and pushed it to the side to keep it open. Then we pulled the slide all the way back, raised it and attempted to ease it forward. The slide didn’t want to “ease” forward and had to be significantly coaxed. With the gun apart, we noted the workmanship was a touch on the crude side inside. The parts were not well finished and the fit was loose. In fact, one of the parts fit so poorly that it nearly prevented reassembly of the slide to the frame after we had mopped up all that oil. Another part, a D-headed pin, was so loose it would slip out of position if the gun were tilted toward the left.

The gun looked entirely new, inside and out. The barrel, chrome-lined for long life, was pristine. None of the parts appeared to have been scraped or marred in the slightest by any firing of the gun, which would have been a normal occurrence. We suspect that if you buy one of these it’ll stay near-new for years to come, if your sample gives anything like the dissatisfaction we got from ours.

This little Makarov was, essentially, a gun we wouldn’t want to own. Once we got it back together (with lots of fiddling and coaxing) and took it to the range for shooting evaluation, we immediately hated this pistol. It stung the hand, the trigger finger, and also the little finger if that digit was rested on the finger extension of the magazine. The slippery black-plastic grip panels shifted in firing, even though the one screw holding them was tight. One of our shooters said he’d far rather fire his .500 Linebaugh. The gun twisted in the hand no matter how hard it was held. The single-action trigger pull was creep defined. Basically two-stage, the trigger went through its first stage easily enough, but then there were three distinct jumps or slips as the trigger was pressed slowly. Finally, with little additional warning, the gun fired. The final break came at about 5 pounds. This was one of the poorer single-action trigger pulls we’ve experienced.

If that wasn’t bad enough, it was nearly impossible to fire the gun double action. It took all the force we could generate with both index fingers on the trigger to get it to fire. One of our testers who is a guitarist with a very strong left index finger was barely able to work the trigger in double-action mode with that finger. The rest of us were lost.

Did we put it together wrong, after our nominal field strip? No. We took it apart again, and with the slide removed, it was just as hard to operate the double-action pull as before. It was a poor design with bad mechanical advantage between trigger and hammer. The gun could not be carried cocked and locked. With no viable double-action pull, serious tactical use of this particular pistol would first require insanity. Next, you’d chamber a round and then lower the hammer by moving the safety to the On position. This drops the hammer without firing the gun. (We tested it with a pencil and it worked properly.) Firing the gun would then require moving the safety to the Off position (up, exposing a red dot), cocking the hammer manually, and then using the creepy single-action pull.

The P-64’s accuracy was good enough, the best 15-yard, five-shot groups going into just under 2 inches. Reliability was also okay, there being one failure for the slide to close during the firing of the first six shots, but none thereafter, as the gun wore in slightly. The magazine was very difficult to load. It held six rounds, each requiring strong pressure against the magazine spring and then a hefty shove rearward beneath the lips. Getting the magazine out of the gun was also a major chore. It released with a spring catch on its bottom-rear edge. The catch was recessed within the grips. The catch spring was strong, and we nearly broke our thumbnail getting it out each time. It went back in easily and positively, thanks to the magazine extension, which acted as a slam pad. The magazine was numbered to match the pistol. There were actually two sets of numbers on the mag, and as you twisted the magazine each would become visible in the varying light. Both numbers were the same, matching the gun’s serial number. That, in fact, may be the sole cause for celebration for the collector who ends up with this pistol, because such matchups are uncommon. Inserting a loaded magazine with the slide locked back required a tug on the slide to chamber a round.

The sight picture was excellent, though small. The sight dimensions were roughly half those of the Star. The front sight was integral with the slide, and its rear edge was slanted to give a sharp and clearly defined post as seen through the rear notch. The rear sight was a tiny dovetailed unit that could be drifted for windage. The gun shot precisely where it looked, another of its few good features. The top edge of the pistol, including sights, was slick enough that it would probably work well out of a pocket, though the mag extension could be a hindrance.

Gun Tests Recommends

Star “S.A.” 9mm Model BM, about $140. Our Pick. On the range we found the Star would give groups on the order of 3.5 to 4 inches at 15 yards, with two types ammo tried, PMC’s 124-grain FMJ and Winchester’s 115-grain BEB loads. Then we tried Speer’s 115-grain Gold-Dot HP ammunition and got several five-shot groups at 15 yards that were on the order of 2 inches. That, we felt, was more than enough accuracy for the gun’s intended purpose. There were no problems with the gun at all. It was comfortable to shoot, shot close to where it looked (or just a touch higher), had a great trigger pull, and was easily handled by all who tried it. We especially liked the easy takedown. The Star could be carried cocked and locked, so you wouldn’t need to rely on a doubtful double-action first shot. We felt the Star S.A. would be an excellent 9mm handgun if you have a need for one and would be willing to forego the greater-capacity lure of many modern 9mms. Unless you plan to miss a lot, that’s not a real problem. We liked the Star quite a bit, and thought it was well worth its modest cost.

Makarov P-64 9×18, about $175 to 200. Don’t Buy. In our shooting tests all the fired rounds got out of the small ejection port perfectly. The gun didn’t seem to have any problems working, though it only worked with half its trigger options. Its double-action pull was useless, and that made a handgun of this type entirely useless, in our view. This gun also treated the shooter in a harsh manner, and had a great lack of finesse overall. This was clearly no Walther PPK. The external metal polish and finish on this all-steel gun were good, and the bluing was deep and even. We can’t help but think it’d be far, far better with a lighter load than we tried, though even that wouldn’t fix all its problems. Many shooters reload for this cartridge, and that would permit assembling lighter loads that would probably be far more pleasant. The hollowpoint 115-grain load by Silver Bear was too hot for this piece, but the round had worked extremely well in another, slightly bigger, Makarov we tested in the August 2003 issue. That Mak had excellent and comfortable grips, an effective slide-release button, and a much better magazine setup. We thought the earlier test gun was a real winner. The one in this test, we felt, was a real loser.