Once again we look at a pair of small 9mm Luger handguns in our ongoing search for pocket-pistol nirvana. Both of these guns are relatively new designs, and we might mention we notice a strong trend in interest in these small backup nines, which every maker now seems to have in one or more versions. This time we have the SIG Sauer P938 Extreme ($823) and the S&W M&P Shield ($449 from FullArmorFirearms.com) on our plate. We tested them with three types of ammo, Russian WPA 115-grain FMJs, Cor-Bon Pow’Rball 100 grain, and Ultramax 127-grain round-nose cast lead. We were unable to obtain any heavy-bullet ammo for this test. Ammo is scarce these days. Here’s what we found.

S&W M&P9 Shield No. 180021 9mm Luger, $449

The current gun-buying mania has the street price of these rather scarce Smiths up to about $600-650 as this is written — if you can find one. There is apparently no shortage of SIG P938s, so the price difference shown here is less than it would appear on the street today.

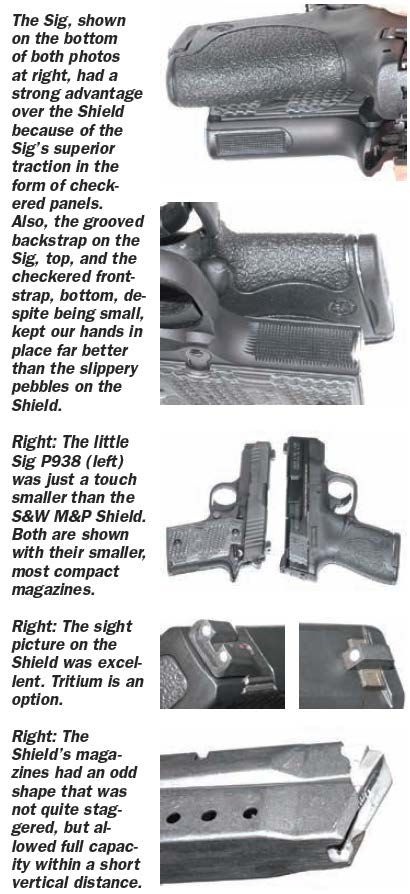

The Shield was a pleasant, compact, slim, nicely made handgun that grew on us. It was easy enough to get it into a pocket of reasonable dimensions, and that’s how we’d pack it. Unlike the SIG with its external hammer and ambi safeties, there was nothing sticking out of the Shield to get caught on clothing. Two magazines came with the gun, one holding eight, one holding seven. The magazines were easy to get out and back into the gun. They had a somewhat staggered design that made them more compact for their capacity. The gun was matte black with semi-slick pebbly inserts on front and rear of the grip straps. We don’t like these because they slip. We think Smith needs more traction at that spot. These were not changeable for size or shape. What you see is what you get, but we were entirely happy with the grip shape and size. There’s a lot of grip angle here, and the gun pointed high for those of us used to the pointing characteristics of the 1911 45 Auto.

The Shield had an external safety on its left side. It was unobtrusive but hard to get to quickly. Because the gun also had a trigger-type safety, the manual safety could be ignored if the user desired, and the gun would still have a great deal of security. The sights were excellent, dovetailed into the slide, and tritium is an option. The rear was secured with a screw so you could adjust the windage. The front was held solely by friction in the dovetail. The trigger pull was heavy and consistent at about 7.5 pounds, and the trigger rebound was short.

Takedown required locking the slide back and applying manly force to the takedown lever to rotate it 90 degrees. Then the slide could be let down to its normal position, the trigger pulled, and the slide comes off the front. Removing the captive double recoil spring was extremely easy. There’s no danger of parts flying across the room, or losing an eye when you put it all back together. We noted a significant fillet on the hook of the S&W’s extractor. It also had a slight pocket to help catch the incoming rounds as they feed from mag to chamber. The striker-locking safety plunger inside the slide is cammed upward by the trigger arm, which actively forces the plunger out of the way. That’s the opposite of the SIG’s design.

On the range we found the Shield outshot the SIG with the FMJ Russian ammo and with the Cor-Bon, and about equal with the cast-bullet load in our limited testing. We had no problems at all with the Smith. The more we shot it the more we liked it. We would have liked to shoot the Shield more but winter weather was uncooperative. Rapid fire was easy, but again we’d like more traction. We noticed a bit of twisting of the gun in rapid fire, but it was nowhere near as bad as the M&P 40 Compact we just tested, even with the hot 100-grain Cor-Bon and with some 115-grain Cor-Bon loads, which we tried but didn’t record.

Our Team Said: All in all, we liked this gun a lot. It’s near the top of our choices for nice small nines. We rated it an A- because we would still like to see more traction on the front and rear straps. We think anyone would be happy with this as their only 9mm pistol.

SIG Sauer P938 Extreme No. 938-9-XTM-BLKGRY-AMBI 9mm Luger,$823

The P938 comes in five finishes, one of which is called the Nightmare. Remember that name. We liked this gun immediately. When we first tried it, we though we had the best of the small nines in our hand. It had a great feel and nice workmanship. It was the ideal small size, easily pocketed, or it could be carried cocked and locked in a small holster. The slide was matte-black stainless on an aluminum frame. The grips on this Extreme-finished version, according to the website (SigSauer.com), were Hogue’s G-10 Piranhas, which means they have gouges in them in lieu of checkering. They felt and looked just fine. The front and rear straps had checkering that helped hold the gun in the right place. The P938 had steel sights dovetailed into the slide. They gave an excellent sight picture and had tritium inserts. The gun had a single-action trigger with ambi safeties. The trigger was too stiff, about 7 pounds, and we’d like it lighter. We liked the ambi safeties. They were out of the way and worked easily. But we learned the hard way to not move them upward with the gun broken down for cleaning. Suddenly we had four odd parts falling off the gun.

Like another SIG we looked at recently, it was not a lot of fun getting this one apart for cleaning. As with the SIG P290 RS tested in November 2012, we had to hold the slide in an exact position of partial withdrawal and then poke out the cross pin, which had a spring detent. It doesn’t come out easily unless you have three hands. With the slide stop out, the slide comes off forward, and inside is the flat-wire recoil spring wrapped around a hefty mandrel, which is the guide rod. It came out easily and so did the barrel. The owner’s manual incorrectly told us to get the recoil spring back in with the correct end forward or we could break something. But the spring was symmetric from one end to the other, so that was a false warning. The manual also suggests replacing the recoil spring after 1500 rounds. Long ago some of us grew up with better guns than are made today. Their springs would last forever. Have the gun companies forgotten how to make springs? We’ve owned and shot a Colt 1860 revolver and a herd of pre-1900 Colt revolvers and a few 1873 Winchesters made back then, and all had their original springs in perfect working order. One of us has a flintlock shotgun well over 200 years old that has its original springs, and they work perfectly despite exposure to not only all the elements, in the case of the hammer (pan) spring, but also the ravages of black powder for all that time.

Reassembly of the P938 was easy, but you had to remember to push down the spring-loaded ejector or the slide could not go on. The extended seven-round magazine would not drop free because its extension hit our hand. The six-shot mag dropped properly.

Our initial test firing made us think we’d found the ideal small nine. Everything was great, we thought. And then the nightmare began. On our next familiarization shooting with a few dozen rounds, we had a handful of failures to fire. Inspection showed the primers were essentially untouched. One or two had the tiniest mark of the firing pin. Some rounds failed to fire from repeated strikes of the hammer. Along with the failures to fire, we had occasional failures to completely eject. Commonly the last cartridge case from the magazine would get caught and mangled on its way out.

We thought we had figured out the problem when the first test shooter said he was not holding the gun hard. We thought his limp wrist was letting the gun fly up and grab the empties. So our Senior Technical Editor decided to hold the gun gently and let the gun kick upward and catch the outgoing empty. On the shot, the empty sailed high and wide. No problem. Then, for the last round in the gun, he gripped the gun hard with both hands. This would let the gun cycle the way it was designed, he proclaimed, and the empty case would leave the gun properly just as high and wide as had the previous one. On the shot the observer didn’t see the empty fly. We searched, and finally looked at the gun. To our amazement, the empty cartridge had been caught by the lips of the magazine and had remained in the gun. That was a first for us.

Inspection revealed a broken extractor. It was such a clean break we couldn’t be sure at first, but comparison with other extractors indicated there should have been more meat on this one. SIG overnighted us a new extractor. The part is investment cast, lightly machined, and has a small stress relief in the form of a fillet along one side of the chunk that broke off. It doesn’t have a fillet behind the hook. We didn’t like the design, but it’s common in today’s handguns. If the extractor had been milled from a forging and heat-treated properly, it would most likely never break in a thousand years. But no one makes guns like that any more, not for $823.

The extractor has a leg extending downward from the main body, and that leg slips behind the rim and drags out the empty. If all goes well, there’s not much work for it to do. It gently slips behind the rim as the cartridge slides into the chamber. Yet something made the old one break. Will the new one hold out? We weren’t able to shoot enough rounds to find out.

Next was the problem of the failures to fire. In the case of failures to fire, the factory manual suggested a thorough cleaning. We pulled the firing pin (just like you’d take one out of a 1911-type 45 auto), but before we did we measured its protrusion out the back, where it is struck by the hammer. It was 0.017 inch. We measured the firing pin protrusion of several 45 autos and found them to be from 0.025 to 0.030 inch. Was the P938’s protrusion marginal?

To check our theory, we put the firing pin in our lathe and turned eight thousandths off the base of its last bulge so that its rearward protrusion became 0.025 inch. To our dismay, we still had failures to fire. All our misfires had been with Cor-Bon ammo. We tried one round three times and it still didn’t fire, and its primer was unmarked. The other two types of test ammunition worked perfectly. Did it do any good to trim the firing pin? We don’t think it did any harm, and we much prefer the protrusion of the pin as we made it. So why didn’t it fire the Cor-Bon? We pulled the barrel and tried various types and brands of ammunition in the chamber. Each and all fit the chamber perfectly. All but the Cor-Bon fired perfectly.

Then again we thought we found the trouble. Inside the slide is a firing-pin safety in the form of a plunger that locks the pin until a cam is moved out of the way by pressing the trigger. Then the plunger is driven downward to the firing position by a light spring. This plunger has to be fully downward to permit the firing pin to fly forward. If the plunger gets stuck upward, the firing pin cannot strike the primer. That plunger is a passive device that relies on a tiny spring to shove it down to the firing position. Most such designs are active, which means the force of squeezing the trigger pushes the device actively out of the way. Not this one. Was the plunger sticking? We thought so, so we took it out.

We drove the rear sight out of the way, pulled out the spring and plunger, re-centered the sight, and tried the gun again. The gun still refused to fire with most of the Cor-Bon ammo. Was the firing pin getting jammed on its own spring? No, it was free. We could see no reason why the gun would not fire. The primers were unmarked. Somewhat dumbfounded, we sent for a duplicate gun to see if it would work, but it was temporarily lost by UPS, so we could conduct only limited function testing on it.

Waiting for the second gun, we closely examined the breech face of the first one. There, we finally found the real problem. The firing-pin hole on the breech face was blocked by a plug of primer material that had been scraped off the bulging fired primer of the Cor-Bon ammo. This little plug was jammed into the firing-pin hole. It spread the force of the firing-pin strike, which didn’t even dent the primer. This, too, was a first for us. Recovered Cor-Bon cases fired in the P938 had their primers blown completely flat. They showed no trace of the firing-pin dent, but they each had a scrape across their face. The scraping action had cut off the protruding primer metal and jammed it into the breech face hole, and that blocked the firing pin.

While the solution seems to be to avoid the otherwise excellent and time-proven Cor-Bon ammo, who is to say another brand of ammunition might not do the exact same thing? The ultimate solution is to test, test, and retest your chosen self-defense ammo. And then do it again.

And we had another problem. We tried to insert a fresh magazine and it stopped dead, with over an inch to go. It had struck a small ledge on the magazine-release button and could not be shoved past it, no matter how hard we tried. With the mag against the inner right side of the chute, its lip hit that ledge, which stopped it completely. The problem was poor fitting of the mag release. We fixed it with a Dremel tool.

All of us who shot this gun were pleased with how it handled our test loads (except for the Cor-Bons, of course). We could fire the gun one handed easily, and shoot it as fast as we wanted. We could not say that about most of the other small nines we’ve shot.

Our Team Said: We would not buy this gun. It was a disappointment to have so much trouble. To start, we gave this gun a C grade. Reason: It worked well with two ammo brands, and it’s always up to the operator to function-test ammo in a defense gun. Then, as problems mounted, we grudgingly moved it to a D grade. Later, we reconsidered — unless the manufacturer warns the customer, a given gun should at least work with any good ammo. So we flunked it. Customers ought not have to deal with any of the problems we had.

Written and photographed by Ray Ordorica, using evaluations from Gun Tests team testers.