The year 2011 marks the 100-year anniversary of the introduction of the John Browning’s most successful pistol. The initial design was actually completed about 1907, but after acceptance by the U.S. Military some four years later, it became known as the 1911 and was chambered for 45 ACP (Automatic Colt Pistol).

To recognize this achievement, we found three affordable 1911-style 45s introduced in the year 2011. They are the Ruger SR1911 No. 6700 45 ACP, $799; Springfield Armory’s $939 Range Officer; and the $799 Desert Eagle 1911G from Magnum Research. The introduction of yet another 1911 from Springfield Armory isn’t surprising; the company has essentially built its formidable reputation on 1911 pistols. For Ruger and Magnum Research, however, these pistols are their first tries at producing 1911s.

All three models featured a 5-inch barrel on a full size frame offering a flat profile checkered mainspring housing below an enhanced grip safety. Thumb safeties were left side only. The front strap of each pistol remained smooth. Each pistol utilized an aluminum trigger that was lined at its contact surface and relieved to reduce weight. Only one gun, the Springfield Armory Range Officer, offered an adjustable rear sight. Only the Desert Eagle was fit with a full-length guide rod. The Ruger pistol alone was fit with three-dot sights and offered a noticeably taller magazine release button. Otherwise, these three pistols were nearly identical.

Besides their basic functionality, these pistols are interesting for another reason. They individually include advancements in 1911 design and finish that shooters of this time take for granted. To better illustrate some of these so-called advancements, we compared our test pistols to a 100th Anniversary, we shot them alongside a 100th Anniversary Limited Edition 1911 Government model from Cylinder & Slide. The retro-1911 is being built for production by Cylinder & Slide, Bill Laughridge’s Fremont, Nebraska, custom house famous for the production of high-quality 1911 parts. On the outside of the current pistols, it is easy to see an improved grip safety, beveled magazine well, aluminum trigger adjustable for overtravel, oversized or ambidextrous thumb safeties, a lowered and flared ejection port, reduced mass hammer and high visibility sights both adjustable and low profile. Most of the upgrades that define the modern era 1911 were developed in the final quarter of the 20th century.

Today’s features are supposed to help the operator shoot the gun faster, safer, and more comfortably, and those upgrades have become more economical. Not long ago, our test pistols would likely have sold in the $1400 range. The cost of high-quality 1911s first took a notable drop with the introduction of Computer Numerically Controlled (CNC) machining. This made accurately machined parts more abundant, reducing hand fitting.

How We Tested

To test we shot each gun with sandbag support from a distance of 25 yards firing three choices of ammunition. These included a budget target round, a premium defense load, and a common recipe of handloaded ammunition. Each round drove 230-grain bullets, the most popular bullet weight for the 45 ACP. Our store-bought range round was Winchester USA 230-grain full-metal-jacket round-nosed ammunition. Our premium round was the 230-grain conically shaped jacketed hollowpoint from Black Hills ammunition. For our handload, we wanted to fire a round that would best represent what a typical 1911 owner was likely to construct. This meant a lead round-nosed 230-grain bullet over the popular Winchester 231 powder. We also used Winchester large pistol primers. For projectiles we chose product number PH 230gr. RN from Rim Rock Bullets of Ronan, Montana ($88 per box of 500 from RimrockBullets.net). We tried a number of handloads topped with bullets by other manufacturers but found that our test guns functioned more reliably using the Rim Rock bullets.

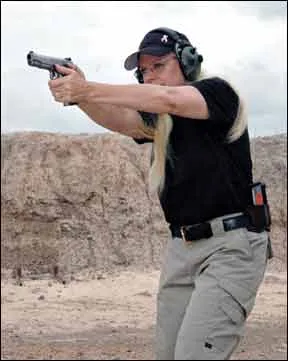

Since the 1911 is a famous fighting and competition gun, we decided to set up an action test at The Impact Zone in addition to our benchrest session. The course of fire would test our ability to draw from a holster and acquire a proper shooting grip, transition between two widely spaced IPSC Metric cardboard targets, perform a magazine change, reacquire the sights and engage a 10-inch round steel target some 40 feet downrange. The IPSC targets were placed 20 feet downrange approximately 45 degrees to the left and right side of the shooter (designated T1 and T2 respectively). The prime target on the IPSC Metrics was the “A-zone,” a rectangle measuring about 5.9 inches by 11 inches. The steel Evil Roy Practice target ($115 from Action Target) was designated P1. It was centered in front of the shooter and painted white for recognition. Forced to change shooting speeds from all but hammering the trigger to performing a controlled press, we wanted to know how much these guns would help us get the job done.

We used a shot recording timer to record total elapsed time from start signal to last shot fired. Our timer was set with a par time according to the elapsed time of our very first run. This run lasted 7.50 seconds. We kept track of how often we finished before par time was up as sort of a pass/fail grade, and we also took note of how many times we needed to fire at the steel to post a hit. For continuity, we chose one holster to be used for all three guns. Our holster of choice was the $55 3-Slot Open Top leather holster from Looper Law Enforcement, an Oklahoma maker that has been in business since 1938. This holster afforded us the option of mounting the gun cross draw or at two different angles along the strong side of the body. Our test shooter utilized the lower forward slot that produced the more upright presentation beneath his strong hand.

We put the trio through identical tasks to see which ones excelled, and found a lot of performance.

Magnum Research Desert Eagle 1911G No. DE1911G 45 ACP, $799

Two 1911 45s are the latest addition to the Magnum Research catalog. The “G” in the product code likely stands for Government model, which is the traditional full-size model 1911. A “semi-compact” version of this same pistol fires from a 4.33-inch barrel and is designated the DE1911C, with the “C” standing for “Commander” length, we would assume. Both guns are listed at the same price and share the same snag-resistant sights, wood grips, and black oxide finish. Capacity was listed as 7+1, but the two Italian-made ACT-Mags displayed eight numbered holes along their shiny blue bodies.

Made in Israel, the Desert Eagle’s blue finish was evenly applied with a matte texture on the frame and along the top of the slide. The sides of the slide were polished, and there were wide, easy-to-grab cocking serrations front and rear. In contrast were the stainless-steel Allen screws on the grip panels, a polished stainless-steel beavertail grip safety with raised surface for better contact, and the stainless steel barrel. The skeletonized hammer was blued. The front sight blade was lined horizontally to reduce glare, dovetailed into place and staked on the left side. The snagproof rear sight, (also dovetailed into place but held by an Allen screw), was aligned with the rear edge of the slide, offering maximum sight radius. Its face was lined in an unusual U-shaped pattern. We found the sights to be clear and easy to read.

The Desert Eagle was the only gun in the test that was fit with a full-length guide rod. Full-length guide rods were introduced to prevent the recoil spring from compressing out of line and binding the action. The recoil spring plug was open in the middle to let the rod pass through. But the stainless-steel guide rod was short enough so that the gun could be field stripped in the traditional manner. Field stripping all three guns began with turning the barrel bushing from 6 o’clock to about 8 o’clock. Once the recoil spring cap was removed, the slide was shifted to align the take down notch with the slide-stop pin. After pushing the slide-stop pin out from right to left, the top end was free to slide off the frame. The Desert Eagle recoil spring came off the guide rod without resistance. The springs inside our other test guns were coiled tighter at the rear to grasp the short guide rod. The guide rod was lifted clear of the barrel. The barrel bushing was then turned to its 4 o’clock position to unlock it from the slide. With the bushing removed, the barrel link was swung downward so that the barrel could be removed by passing it through the front of the slide.

Before reassembly, we made sure the gun was fully lubricated to protect it during our long range session. This meant oil in the barrel lugs, barrel link, plus the slide and frame rails. In addition we put some oil inside the hammer relief beneath the slide. We also worked a drop of oil into the trigger disconnector, and along the sides of the hammer. With the slide locked back to expose the barrel, our last point of lubrication was the surface area that would contact the bushing during lockup. In terms of construction we felt that the slide stop and the thumb safety could have been fit a little tighter, but we can’t lay blame on these components for any type of malfunction.

From the bench our Desert Eagle favored both the Rim Rock hand loads and the Winchester FMJ ammunition with an average group size of about 1.6 inches. Best single group measured 1.1 inches across firing the handloads. This topped the field when firing the round nosed ammunition. The best group firing the Black Hills hollowpoints measured about 2.3 inches across. All three guns posted a similar velocity with this round, 814 fps on average. In terms of accuracy when firing the hollowpoints, the Desert Eagle finished third. But a 2.6-inch-average five-shot group at 25 yards was fine.

The Desert Eagle was the only pistol that allowed every member of our staff to easily reach the magazine release. The magazine release on a 1911 is not necessarily supposed to be immediately beneath the shooter’s strong hand thumb. The technique is to roll the pistol in the strong hand to bring the release button to the shooter’s thumb. We knew this would help during our action test where completing a reload smoothly could make or break a fast run. In our action test we were able to beat the par time 8 out of 10 runs. We needed a second shot on steel only four times and a third shot once. Three runs took less than 7 seconds, and our best elapsed time shooting the Desert Eagle was 6.47 seconds. We learned we could go fast on every aspect of the test, but needed to slow down for the reload. Actually, we’re not sure if we had to slow down or merely avoid tensing up. This also applied to pressing the trigger. We overplayed the trigger and pulled one shot low and one shot right of the A-Zone on T1. On T2, the right-side target, we had one hit low and one hit low-left. These were among the best results in the test. The Desert Eagle offered a clear sight picture that could be read quickly. The trigger didn’t present any barriers, such as creep or an inordinately long pull, and the magazine could be released quickly. Not having to struggle with the magazine release, we were able to stay relaxed. The basepad, and the sheer length of the ACT magazines, helped us complete the reload so we could better concentrate on reacquiring our grip, aligning the sights and breaking the final shot.

Our Team Said: This is an $800 pistol that should satisfy all but the buyer who wants or needs a custom gun.

Ruger SR1911 No. 6700 45 ACP, $799

On one side of the top end it simply read “RUGER” in all capital letters, then “Made in USA.” Engraved on the other side was the Ruger Phoenix emblem. We think this was pretty low-key promotion for a pistol few thought would ever appear in the Ruger catalog. The Low Glare Stainless finish was understated as well, but this did distinguish the SR1911 from our other test pistols. Accents were blackened components such as the mainspring housing, beavertail grip safety, set pins, slide stop, thumb safety, magazine release, the Novak style white dot sights, and the outer surface of the heavily relieved hammer. The checkered wood grips carried the Ruger emblem on both sides.

The Ruger SR1911 arrived with two magazines. One was an 8-round magazine with its shiny stainless body displaying numbered viewing holes for each round. It also carried a wide polymer basepad that, when loaded, sat slightly ajar, exposing about 0.1 inch of the magazine body. A lug at the front of the basepad buttressed the magazine against the front strap. The second shiny magazine carried 7 rounds, offered viewing holes (none of which were numbered), and had a fixed bottom plate drilled and tapped for a base pad. During our action test, we began with the 7-round magazine and loaded to the 8-rounder to take advantage of the base pad or, slam pad as some call it.

From the shooter’s perspective we thought the rear sight unit was thin and didn’t block as much light as we would prefer. But the narrow, moderately tall front sight made the sights easier to read. For target work (especially against the steel target that was painted white), we found the three-dot system distracting.

Elsewhere, the slick finish resisted dirt and came out of our test sessions looking like we had just opened the box. But the finish also made the smooth front strap more slippery. Racking the slide, we noticed that the Ruger was much more heavily sprung that the other guns, unnecessarily in our view. But, fit and finish, lockup and movement of the operating levers were tight as a vault. In terms of sheer integrity, this was a superior firearm, our testers said.

In a blindfold test, our shooters could tell which gun was the Ruger every time. The triggers on the R.O. and the Desert Eagle showed little or no sense of takeup before the feeling of snapping a twig. The Ruger trigger offered a soft compression before reaching its break point. What shooters like best about the single action 1911 trigger is that the break happens quickly. The period of time during which the sights can be drawn out of alignment is very short. With the Ruger, we felt it was giving us more time to get it right or get it wrong, depending upon how you look at it.

From the bench the Ruger failed to distinguish itself with either of our lead or FMJ round-nose ammunition. But it did tie the Springfield Armory Range Officer for smallest overall group (about 0.7 inches across) when firing the Black Hills JHP rounds. In a statistical dead heat for average group size, the SR1911 actually topped the R.O. by 0.1 inch in largest size group. We would be interested in testing this gun with other defense rounds.

To complete the action test we had to change out the left-side grip panel. Our problem was that the stock grip was too wide and too round to let us operate the magazine release quickly. Despite the release button protruding an extra 0.07 inch from the frame (0.16 inch vs. 0.09 inch on our other guns), we just couldn’t get there. Add to this that the detent spring beneath the magazine release button was too strong, in our view. One other condition was that some of our staff had difficulty compressing the grip safety. Both problems were cured by replacing one or both grip panels, which to our way of thinking is a personal choice and no fault of the manufacturer. Grip panels actually have two measurements that effect shooter grip. One is maximum height or the distance of the outer surface to the frame at its greatest point. Another element is how steep the climb is to maximum height from where the edges of the panels meet the frame. For most shooters the more square a 1911 feels in the hand, the easier it is to shoot and manipulate. Long fingers can help, but the girth of the shooter’s palm is another key consideration.

For the action test our shooter applied a thin flat grip with the surface directly behind the magazine release relieved to provide a guide line. Another aspect of the SR1911 that helped us reload quicker was a deeper, more effective bevel to the magazine well. Time saved during the faster magazine release was better spent completing the reload and lining up our final shot. We were able to beat the par time 8 out of 10 times. Both over times were blowouts in which we fired three and four extra shots on the steel. Once we lost our concentration, a coordinated trigger press seemed harder to regain. We were able to hit the steel on the first shot during our remaining runs, save one where a single extra shot rang out at the 7.11-second mark. Six of our runs took less than seven seconds and our best elapsed time was 6.17 seconds. In terms of accuracy we saw that our hits were creeping to the left with each run. This would be the shooter over reacting to the soft break trigger. On T2, the right hand target, we also saw hits to the left of center where our shooter became impatient, breaking the shot before the sights fully entered the A-zone.

Our Team Said: If there were any complaints, such as the size of the grip panels, the lack of grip at the front strap, or the softness of the trigger, these matters can be easily addressed. In the meantime, the starting point was a handsome pistol with structural integrity and vault-like lockup. These are the two most valuable features in any pistol and the most difficult characteristics to produce.

Springfield Armory Range Officer No. P19128LP 45 ACP, $939

The overview on the Springfield Armory website reads that one of the goals in designing the Range Officer was for it to be acceptable in many different styles of shooting competition. The idea was to offer the same quality of more expensive models but keep the price in check by including only the most necessary parts. Further upgrades to the Range Officer (or any other 1911 for that matter) would be easy to obtain.

In our view, the R.O. came with the single most helpful upgrade already in place. That would be the fully adjustable rear sight. Mounted deep into the top of the slide, it blocked out plenty of light and offered the clearest relief of the front sight blade among our test pistols. The front sight blade was, like our other pistols, dovetailed into place but it was staked from the top as well. For those considering carrying the Range Officer in a belt holster, it will be difficult to find leather with a retention strap that will reach across the big rear sight blade. Thankfully, the R.O. arrived with an open top belt slide holster plus a matching double magazine pouch. Formed from a non-marring plastic, the holster was tension adjustable.

The Parkerized finish was not pretty but it seemed to be quite durable and unwanted glare didn’t have a chance. The magazine well was aggressively beveled and the detent on the thumb safety was even more crisp than the one found on the Ruger. We liked the placement of the side plate that carried the thumb safety on this pistol better than on the others. The plate rode higher on the frame and further away from the web of the shooter’s hand. This made the Range Officer more comfortable to shoot as some of our staff complained of irritation along the inside of the right hand thumb after firing the other pistols.

At the range we learned there is no substitute for a good sight picture and a consistent trigger. When shooting on the move during our photo sessions, we were able to consistently hit the Evil Roy target shot after shot. From the bench, the Range Officer edged the Ruger pistol, delivering average groups measuring 1.5 and 1.6 inches across firing the Black Hills hollowpoints and our Rim Rock Bullets handload, respectively. Average sized groups shooting the Winchester USA rounds measured 2.1 inches across.

The Range Officer shipped with two blued-steel 7-round magazines that functioned flawlessly. (The Range Officer also functioned with the 8-round magazines we had on hand). The fixed bottom plates were drilled and tapped for base pads but none were supplied. We feared this would slow down our reloads during our action tests. In fact this did bite us on the hand (literally as our shooter’s palm was pinched a couple of times as he closed the magazine against the front edge of the receiver). But the only run where we didn’t beat the par time came on a different run when human error and not pinched skin interrupted the reload. The result was two extra shots and an elapsed time of 8.69 seconds. Altogether 7 of the 10 runs took less than seven seconds and only three, including the run described above required an extra shot on the steel. The fastest single run took 6.11 seconds. Three of the shots on target T1 were low of the A-zone, and T2 showed 4 shots that were to the left but at the proper height. More visual patience on the part of the shooter might have resulted in a clean target.

Our Team Said: The more expensive Range Officer was our top performer overall, even if our test shooter was too eager on the second target. The team said its appearance was understated, but you have to know what you are looking for. The superior sights made the most difference, in our view, and maybe the application of this same system would have improved the scores of the other pistols, too. Adding a sight upgrade to the two $800 pistols would make their cost about even with the R.O., so we think the difference in price between our test guns was negligible.

0911-MAGNUM-RESEARCH-DESERT.pdf