In ourrecent test of three small semi-automatic pistols chambered for 32 Auto, we learned that they could be fired quickly with little recoil. In this test we upped the power to 380 ACP and tried again with three more guns that were nearly identical to our 32s in size, action, and mechanical operation. In two of three cases, we repeated our tests with guns made by the same manufacturer. These were the $573 Walther USA PPK 380 and the $419 Taurus PT138BP-12. Our third 380 was the $330 Ruger LCP. This was a very close copy of the Kel-Tec P3AT last tested in our March 2004 issue, and which we test head to head with the LCP later in this issue to see just how similar they are.

The 380 ACP is also referred to as 9mm Kurz or 9mm Short. The length of a 380 Auto cartridge case is about 2mm shorter than the popular 9mm Parabellum case. Bullet diameter is the same. In fact, this same bullet diameter can be shared with more powerful ammunition such as 38 Super. By moving up to 380 ACP we hoped to gain an advantage over the 32 Auto pistols by delivering greater stopping power without significantly increasing recoil. The advantage of chambering ammunition with a short overall length kept these guns small and concealable.

We had been surprised how well our 32-caliber pistols performed in our accuracy tests, so we tested our 380s from the same distance of 15 yards. Test ammunition was MagTech 95-grain FMC, Federal Premium 90-grain Hydra-Shok JHP, and Hornady 90-grain JHP/XTP rounds. We also performed the same action tests with our 380s as we did with our thirty two caliber pistols. But this time we limited all strings of fire to six rounds, shooting each gun until empty. We didnt think emptying the 12-round magazine of the Taurus pistol was necessary. However, we wanted to make sure we experienced any change in handling or reliability as each gun ran dry.

The MagTech ammunition was used exclusively during the action tests. We fired at an IDPA-style target from a distance of 3 yards and the drill was completed three times. After recording total elapsed time, we subtracted the time it took to break the first shot to arrive at the split time (elapsed time between shots). We wanted to know how quickly each gun could be fired. We also checked accuracy on the cardboard targets to see how well we could group 18 shots in relation to the 8-inch circle embossed on the target, which served as our point of aim. In an effort to replicate a close-quarter situation, all shots were fired strong hand only. Aiming was achieved with a mix of sighted and point-shooting technique. Tests were performed outdoors at the Impact Zone (theimpactzonerange.com) in Monaville, Texas. Lets see how our three guns performed.

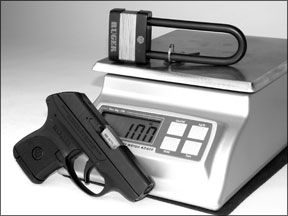

Ruger LCP 380 Auto, $330

If any gun introduced at the 2008 SHOT Show created a splash, it was the Ruger model LCP. The LCP or, Lightweight Compact Pistol, could be thought of as a clone of the Kel-Tec P-3AT. It even came in a similar cardboard box with comparable zippered gun rug. The LCP is a locked breech semi-automatic pistol that holds 6+1 rounds and shares almost identical dimensions with the Kel-Tec, as Ray Ordorica details elsewhere in this issue. Its three main components are the “through hardened” steel slide, aluminum sub-frame, and grip frame. However, we can point out several differences between the Ruger and Kel-Tec products. The Kel-Tec grip frame is listed as being Dupont ST-8018 polymer. Rugers grip was listed as being constructed from glass-filled nylon. The Ruger LCP relied on the magazine to complete a greater area of the front strap. Checkering along the sides of the Ruger was more handsome than the Kel-Tec but less effective, in our view. There was an indentation for the thumb and/or index finger that gave it a look comparable to grips found on the Browning Hi Power. Graphics molded into the grip frame made for coordinated overall look. The magazine release was larger and slightly easier to operate than the Kel-Tec design. Operationally the LCP can be locked back thanks to the addition of a slide release. This lever was set into the frame to avoid adding a snag point but was lined for grip and easy to operate. Chamber-loaded indication was provided by a cutaway of the barrel at the point of ejection. The extractor was also contoured downward to add to this window. When the chamber was loaded, we could see the case rim and a portion of the case.

Before removing the slide, the owners manual instructs the operator to inspect the chamber with the slide locked back. Then, return the slide to its forward rest position. Next, shift the slide to the rear about 1/16 inch or more and pry the takedown pin from the left side of the frame using a screwdriver. Underneath the slide we found a steel guide rod surrounded by two coil springs one underneath the other. The spring closest to the guide rod was constructed of finer wire than the spring that surrounded it. The only trick to reassembling the LCP was to insert the takedown pin at an upward angle then press down to bypass the retention spring.

At the range we were reminded that the LCP, which at one time might have been called a vest pocket gun, was not going to adapt readily to benchrest fire. The lack of available grip made it all too easy for the support hand to interfere with the trigger finger. Whereas we often rest a portion of the gun directly on a sandbag or solid rest, we did our best to envelop the pistol in both hands and rest them directly upon support. As we learned to maximize the accuracy of our shots from this position, we found that we had to control more recoil than the 32 ACP powered semi-automatics. To begin with we saw two separate groups forming on the target. Without a steady grip a loose hold printed our hits high on the target and a controlled grip printed them lower. Ultimately, we found that we could regularly achieve five-shot groups that averaged about 3.0 inches to 3.5 inches across with each variety of ammunition we tried.

It took a lot of work to shoot the Ruger LCP as if it were a target gun. Thats why we looked forward to our action test to provide more pertinent information. Fired from a distance of 3 yards we pushed the gun towards the target aggressively and tried to keep the outline of the rear face of the gun on target as we returned from recoil.

Certainly we were faced with greater recoil than was produced by the 32s, but it was neither sharp nor difficult to control. The key to accuracy and a quick time was to move the trigger finger forward the same distance every time to make sure the gun reset consistently and fired in time. The results of our three strings of fire produced a group that was remarkable not so much for its tight one-holed appearance but rather its even circular shape. In our first string of fire we dipped the muzzle and landed two shots low and to the right. But the remaining sixteen shots defined the circle by producing about an 8-inch group. Checking our Oehler chronograph and our Competition Electronics shot-activated timer, the MagTech ammunition used for this test was delivering about 137 ft.-lbs. of muzzle energy at a rate of about one hit every .21 to .25 seconds.

Throughout our tests we suffered no malfunctions. The Ruger LCP may not be alone in offering a lightweight vest pocket 380 Auto, but its performance certainly makes it a contender.

Walther USA PPK VAH38002

380 ACP, $573

The Walther PPK design harkens back to 1931. It had several classic design features that distinguish it from todays pistols. In order to remove the barrel and slide for cleaning, we pulled down on the trigger guard and left it ajar. The blowback design meant the barrel remained stationary attached to the frame. The magazine release was placed high on the left side of the frame at the upper rear corner just below the slide.

Our current test pistol was a stainless-steel model outwardly identical to the PPK 32 ACP we tested last month. The PPK 380 ACP is also available in blue steel for the same price. Just ask for the pistol with its catalog number ending in the numerals “003.” Like the 32-caliber pistol, our PPK 380 ACP arrived with two six-

round magazines, one of which offered a flat base pad and the other an extension for the pinky finger. Of the differences we found between the two pistols, we think one was intentional and the other perhaps a matter of quality control.

First, the double-action trigger was inordinately heavy. We would have trouble finding another semi-auto with a 20-pound double action trigger pull in our archives. But a heavy double-action pull is to be expected in this design. There is little mechanical help for the trigger to raise the hammer and drop it with force in the Walther PPK design. There isnt a lot of weight bearing surfaces to polish or refine. Force of the hammer drop is almost completely derived from the energy provided by the mainspring that is housed inside the grip. Aftermarket alternatives including parts and services that would lighten the trigger are limited with reduced reliability in the balance. Breaking the gun in might be the best first option.

We were also surprised at how sharp the cuts were on the cocking serrations on the slide. Use of the word serration is traditional for describing cuts in the slide to add grip. We never suffered an actual abrasion, but the lines on the decocker as well as on the slide ultimately turned us off to this pistol. In this case we would have liked the option of being able to use a slide stop lever to let the slide forward in order to reduce the amount of times we had to pull on the slide. But a slide stop was not part of the design.

The heavy double-action trigger did not affect our bench rest session because all shots were fired single action only. Our efforts paid off with the Walther delivering groups measuring about 2.5 inches across when firing our hollowpoint ammunition from Federal and Hornady. The top performer in this test was the combination of the Walther PPK and the 95-grain full metal case ammunition from MagTech. Average group size was 2 inches across.

During our bench session with the Walther, we had to adjust our grip to make room for the tip of our trigger finger. We also found that the left-handed shooters had an advantage when firing the PPK. This was because our right-handed shooters had to be careful where they put their thumbs. Otherwise, the right-hand thumb was hit by the decocker. Naturally, we could tuck the thumb underneath the left hand, but with so little available space on the grip we preferred to apply as much open palm to the grips as possible. This meant taking care to angle the right-hand thumb away from the frame.

In our action test we expected that the extra-heavy pull necessary for the first shot would interfere with our speed or smooth operation. Happily, its affect on performance was minimal. Nevertheless we found it easier to overcome the trigger when standing with the gun tucked inside the shooters strong hand. Firing the MagTech ammunition, we were able to empty the magazine and deliver six shots in elapsed times of 1.31, 1.10 and 1.31 seconds. Based on our faster runs, this computes to split times of about .19 seconds. But what did the target look like?

We delivered a couple of shots high, in the “head” area of our humanoid target. The majority of our shots were in a vertical column centered on the target. The body of the group measured about 10 inches top to bottom. But after performing the rapid-fire

drills, our hands ached from recoil energy transmitted into our hands. Despite our dislike of handling the PPK 380, this gun performed above expectation.

Taurus PT138BP-12,

1-138031P-12 380 ACP, $419

Compared to the 32 ACP Taurus PT132SSP tested last month, the PT138BP-12 is just a little bit taller. The dash-12 stands for 12 rounds of ammunition instead of 10. Together with the slightly larger-diameter ammunition, it stands to reason that the 380-caliber pistol would be bigger top to bottom.

Between the two pistols we found some differences that we could quantify and some that became apparent when simply holding the gun in the hand. Grip circumference of the 380 was measured to be larger than the 32, but the narrower sides made it feel smaller in the hand. Trigger span, measuring from the bow of the trigger face directly rearward to the backstrap, was measured to be 0.1 inch less, but it seemed shorter still. The feel of the trigger on our 380 required that we press almost all the way to the frame after a long take-up. Forward movement to the trigger reset point was short, making the span feel shorter.

At the range we learned that the trigger return spring was very light. This meant that the shooter had to work harder to be more consistent in releasing and resetting the trigger. This came up again later when we attempted our rapid-fire drill. The sights were the Heinie Straight-8 design. The rear unit was adjustable for windage only with opposing movement controlling shot placement. Clockwise movement of the tiny screw moved hits left and counterclockwise moved hits to the right. As always we took care to set up our benchrest so that our gun was level with our point of aim as it sat in the sandbag rest. As much as we liked the sight picture, the resulting point of impact at 15 yards varied from about 6 to 10 inches high from our point of aim.

The MagTech ammunition hit the highest and the Federal rounds hit the lowest. We were able to land the 90-grain Federal Hydra-Shoks inside the 4-inch bullseye by holding our aim at the bottom edge of the paper where we had pasted an aiming dot to compensate for the difference. During our slow fire from the bench we suffered one light hit on the primer of the Hornady ammunition and another on the primer of the MagTech rounds. During our chronograph session we also suffered one failure to feed with two rounds of the Hornady ammunition remaining inside the magazine.

Because the Taurus firing mechanism reset after each stroke of the trigger, we were able to practice for the action test by dry-firing. Working on our trigger press and release was important because the weak trigger-return spring demanded that the operator swing the trigger forward and back with precision. During live fire we found that the fastest way to land accurate hits with the Taurus was not to stage the trigger for the first shot and then begin stroking.

Instead we practiced snapping the trigger evenly in a cadence of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, before our first run. We were able to achieve our fastest runs with the Taurus. First shots were not hindered by a heavy or inordinately long movement, and they broke earlier than during our tests of either the Walther or the Ruger pistols. Elapsed times between shots ranged from .17 to .19 seconds over the course of all three runs. Our target showed four shots pulled down and to the right. Eight of the remaining 14 shots were also pulled to the right of center. We credit this with shooter error due to unbridled enthusiasm.

No malfunctions were experienced during the rapid fire drill. We found that the Taurus mechanism responded more reliably to forceful action than to a careful controlled press. We liked the way the PT138BP-12 felt when we were shooting fast. Unfortunately, the malfunction and light hits we experienced must be taken into account.

0608-380-ACP-ACCURACY-CHRONO-DATA.pdf