In a major ruling on June 28, the Supreme Court has scaled back the power of federal agencies to make up regulations that U.S. gun owners must follow under what has been called “Chevron deference,” putting into question recent Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) rules on pistol braces and what it means to be in the business of selling firearms.

By a vote of 6-3, the justices decided Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo and Relentless v. Department of Commerce, overturning the 1984 decision Chevron U. S. A. Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc. The 1984 Supreme Court decision gave rise to what has been known as the Chevron doctrine.

Under that doctrine, if Congress left a law or portions of a law ambiguous, a court usually had to uphold an agency’s interpretation of the statute. But in a 35-page decision by Chief Justice John Roberts, the court threw out the Chevron doctrine, calling it “fundamentally misguided.”

As Chief Justice Roberts put it in the Court’s majority opinion, “[t]he Framers … envisioned that the final ‘interpretation of the laws’ would be ‘the proper and peculiar province of the courts.’”

Under “Chevron deference,” federal courts bowed to any “permissible” reading of a federal statute made by a federal agency if the court determined that the intent of Congress under the statute was unclear.

Seemingly, the Court had already decided not to extend any deference to ATF when the Court rejected ATF’s ban on bump-fire stocks in the recent Cargill ruling. In the Cargill case, ATF had tried to define a bump-fire stock as a “machinegun,” a move the Court rejected after extensive briefing and oral arguments that sought to understand the differing mechanics of semi-auto and automatic rifle fire.

While the Loper Bright and Relentless cases dealt with the federal government’s regulation of commercial herring fishing, overruling the Court’s Chevron decision will have far-reaching consequences for federal firearm regulations.

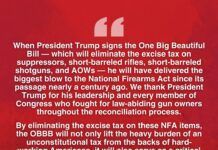

In recent years, most federal gun control has been created through regulations implemented by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF). This includes ATF’s treatment of all pistols with attached stabilizing braces as short-barreled rifles, ATF’s redefinition of the term “frame or receiver” to effectively ban parts used by hobbyist gun builders, and ATF’s attempt to expand who must be licensed as a gun dealer before selling firearms.

“By overruling Chevron, the Court properly restored our constitutional order by ensuring that the judicial branch, rather than the executive, interprets the law,” Randy Kozuch, executive director of the NRA Institute for Legislative Action, wrote in a statement. “The ruling benefits NRA’s ongoing efforts to hold Biden’s ATF accountable for exceeding its authority and punishing peaceable gun owners.”

Last year, the ATF reclassified guns equipped with pistol braces as short-barreled rifles under the National Firearms Act of 1934. By doing so, the ATF effectively banned pistol braces by requiring more-stringent background checks for buying them, assessing a $200 tax, and classifying them alongside short-barreled shotguns, suppressors and pre-1986 machine guns.

This year, ATF changed what it means to be “engaged in the business” of selling firearms. Before the change, people only needed to apply for a Federal Firearms License as a dealer if they earned a living selling guns. The ATF’s new definition, finalized in April, requires people to register as FFLs if they repeatedly attempt to sell guns with the intent of making a profit — even in cases where the seller fails to find a buyer.

The Supreme Court’s ruling will bolster the case against the ATF rules, according to the National Shooting Sports Federation. “The ‘engaged in the business’ rule and the pistol-brace rule are dead on arrival,” said NSSF spokesman Mark Oliva. “They just need a day in court.”

Chevron deference, Roberts explained in his opinion for the court on Friday, is inconsistent with the Administrative Procedure Act, a federal law that sets out the procedures that federal agencies must follow, as well as instructions for courts to review actions by those agencies.

The APA, Roberts wrote, directs courts to “decide legal questions by applying their own judgment” and therefore “makes clear that agency interpretations of statutes — like agency interpretations of the Constitution — are not entitled to deference. Under the APA, it thus remains the responsibility of the court to decide whether the law means what the agency says.”

Overturning Chevron arose from a rule issued by the National Marine Fisheries Service. The agency had required the herring industry to pay about $700 a day for carrying observers on board fishing vessels to collect data about their catches and monitor for overfishing.

Justice Clarence Thomas’s concurring opinion emphasized that the Chevron doctrine was inconsistent with the Administrative Procedure Act and with the Constitution’s division of power among the three branches of government. He said the Chevron doctrine required judges to give up their constitutional power to exercise their independent judgment and it allowed the executive branch to “exercise powers not given to it.”

Roman Martinez, who argued the case on behalf of Relentless, one of the fishing companies, wrote in a statement, “By ending Chevron deference, the Court has taken a major step to preserve the separation of powers and shut down unlawful agency overreach. Going forward, judges will be charged with interpreting the law faithfully, impartially, and independently, without deference to the government. This is a win for individual liberty and the Constitution.”

He described Relentless Inc. as a a small New England fishing company. The company challenged an agency rule requiring private fishing companies to pay for expensive at-sea government observers to ride on their vessels and collect data on federal fisheries.

He added that the decision is a landmark holding of administrative law that will recalibrate the balance of power between agencies and courts. He said its implications will likely be felt across virtually every federal agency.