38 Special Problem in 357 Mags

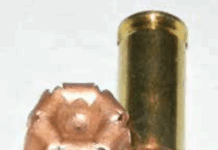

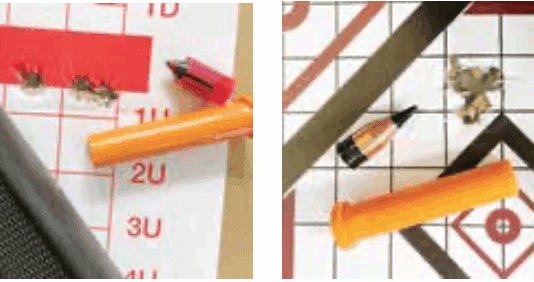

I enjoyed the article on 38 Special lever-action rifles, but I think you missed a very important warning. The 38 Special and 357 Magnum are not interchangeable, for reasons other than the strength of the action. I have a Marlin lever action in 357 caliber. I decided to sight it in with 38 Special rounds and then change to 357 and adjust the sights. After about 20 or 30 rounds of 38 Special, I switched to 357. When I tried to rack in the second round, it wouldn't seat. The problem was that the 38 Special rounds carboned up the chamber, and when the 357 round was extracted, only about half of the cartridge came out. I had to have a gunsmith remove the front half of the casing. I only shoot 357 rounds in my rifle and revolver since then. I have never seen this in any article which discusses using 38 Special ammo in a 357 chamber.

38 Special Problem in 357 Mags

I enjoyed the article on 38 Special lever-action rifles, but I think you missed a very important warning. The 38 Special and 357 Magnum are not interchangeable, for reasons other than the strength of the action. I have a Marlin lever action in 357 caliber. I decided to sight it in with 38 Special rounds and then change to 357 and adjust the sights. After about 20 or 30 rounds of 38 Special, I switched to 357. When I tried to rack in the second round, it wouldn't seat. The problem was that the 38 Special rounds carboned up the chamber, and when the 357 round was extracted, only about half of the cartridge came out. I had to have a gunsmith remove the front half of the casing. I only shoot 357 rounds in my rifle and revolver since then. I have never seen this in any article which discusses using 38 Special ammo in a 357 chamber.

Cowboy Up with Lever Guns From Cimarron, Uberti, Taylors

Good, modern-day cowboy-action shooters can push lead out of lever-action rifles at about 10 shots in two seconds. That's fast. Tuned guns help. SASS (Single Action Shooting Society) rules allow only original or replica centerfire lever- or slide-action rifles that reflect the period between 1860 and 1899. Caliber can be the minimum, 32, to the largest, 45. Rifles must have exposed hammers, tubular magazines, and barrel lengths longer than 16 inches to qualify for matches. That means clones of the Winchester Model 1866, Models 1873, and Model 1892, are contenders, as well as the Marlin 1894 and reproductions of the Colt Lightning. Many competitors run reloaded 38 Special to the minimum velocity. SASS rules require rifle ammunition to have a maximum muzzle velocity of 1,400 fps or less. The 38 Special has other attributes that make it popular, such as mild recoil, less cost, and ease of reloading.

Ruger Introduces New 10/22 with Modular Stock System

Gun Tests Editor Todd Woodard said, "The Modular Stock System allows for length-of-pull adjustment to accommodate shooters of various sizes as well as variations in thickness of outerwear. With a low comb height and 12.5-inch length of pull, this 10/22 model is ideal for training younger shooters."

300 Win. Mag. Bolt Rifle Test: Savage, Steyr, Barrett Shoot Out

Rifles set up for long-range precision shooting are specialized instruments with features that allow the user to consistency wring out accuracy at or beyond 1000 yards. We recently looked at three precision rifles in the big-boy cartridge of 300 Winchester Magnum to see what hit our wallets had to take to get in on the fun of precision rifle shooting. At the low end of the price range, we tested a Savage 110 BA Stealth and two that were nearly four times the cost, a Steyr SSG 08 and Barrett MRAD. After the dust had settled, we determined the cost of the rifle did not make much difference in its accuracy performance. All rifles grouped sub minute of angle, requiring us to measure to two decimal places, or hundredths of an inch, to determine the top gun in accuracy. Spoiler: We shot the smallest group with the Savage. What separated the low-cost 110 BA Stealth from the premium-priced Barrett and Steyr were features that made the premium rifles easier to shoot or were more adaptive to the user's needs.

We went to MidwayUSA.com to fit the rifles with two affordable variable-power scopes and mounts. The first was a Bushnell Engage 4-16x44mm with Weaver Tactical Skeleton rings. The second was a Leapers UTG Accushot 4-16x56mm scope with a Bobro 1-Piece QD mount. The Engage scope uses what Bushnell calls a Deploy MOA reticle. We felt this scope offered clarity and sharpness. The locking turrets were easy to use and require no tools to adjust windage and elevation. We also liked the parallax adjustment, which we feel is a requirement for long-range shooting. The eyepiece was also easy to adjust and allowed different testers to dial in sharpness for their individual eyes. The magnification had just the right resistance so we could be on target and adjust magnification by feel, but not have to move out of position to make the optical changes we wanted. The Weaver rings are also a low-cost option that easily dealt with the recoil of the 300 Win. Mag. Since the Weaver set up used separate rings, we were able to ensure the Bushnell was well attached to the Picatinny rail of the Savage. The Leapers UTG Accushot 4-16x56mm performed similarly to the Bushnell but offered an illuminated reticle in either red or green, which some testers liked. A black reticle can be more difficult to aim on a black target. It featured a mil-dot reticle with a bubble leveler, letting the user know if the rifle is canted, which could affect the shot. Both scopes featured a second-focal-plane reticle, so the magnification needs to be set on a specific magnification for the reticle to be used in range estimation. The Bushnell needs to be dial to 16x, the highest magnification, and the Leapers needs to be dialed to 10x. In our opinion, the reticles and magnification ranges were suitable for long-range work, well over the yardage found at most public shooting ranges. We were pleased at the performance of both scopes.

September 2018 Short Shots: Rifles and Rifle Accessories

The Smith & Wesson Performance Center and Thompson/Center Arms announced the launch of a new bolt-action chassis-style rifle — the Performance Center T/C Long Range Rifle (LRR). Co-developed for extreme long-range shooting, the Performance Center T/C Long Range Rifle is built on an aluminum chassis stock and is available in 243 Winchester, 308 Winchester, and 6.5 Creedmoor. Tony Miele, general manager of the Performance Center, said, "With the growing popularity of long-range precision shooting, we wanted to ensure our customers had an option available from the Performance Center. The new Performance Center T/C Long Range Rifle also includes a 20-MOA Picatinny-style rail and a 5R rifled, fluted barrel.

VALUE GUIDE: Centerfire Bolt-Action Rifles (Multiple Chamberings)

Log on to Gun-Tests.com to read complete reviews of these products in the designated months. Highly-ranked products from older reviews are often available used at substantial discounts.

Rifles Not Ready for 50 States

Please consider the following. The issue of gun control, regardless of degree, is a cultural issue — not a national safety issue. When the Constitution was written, less than 15% of our population lived in urban areas. Today, approximately 80% of our population is urban. However, cities account for only about 5% of the geographical landmass of this country. We now have two opposing gun cultures in this country — with urbans believing guns are only for killing people and rurals viewing them as tools, much as a rod and reel are for fishing.

Threaded-Barrel Rimfire Rifles: Savage, CZ, and Ruger Compete

As we noted a couple of issues ago, the shooting community is seeing more and more factory-supplied threaded barrels on rifles to allow application of muzzle devices, including sound suppressors. In that previous test of 308 Winchester and 300 Blackout bolt rifles, we noted generally better accuracy with the rifles when fitted the cans, but we didn't cover how much more pleasant the centerfire rifles were to shoot. Our shooters noted a marked difference in recoil at the shoulder, and, perhaps more profound, the lack of muzzle blast and report created better shooter conditions behind the gun. A lot of things can contribute to flinching and missing, and noise and a sharp push into the shoulder are two of them.

This time, we cut way down on the noise — to practically nothing, which has its own appeal — by shooting three rimfire bolt-actions side by side with a suppressor. We realize one of the drawbacks of shooting quieter is the initial cost of the cans as well as the red tape. We can't do much about the red tape other than to say get yourself an NFA trust, depending on where you live. But we can offer a strategy for making the can work across many firearms, so you can amortize its cost per shot. But first, the rifles.

We ordered all three rimfires online. The rifles, a Ruger American Rimfire, a CZ-USA 455, and a Savage MKII FV-SR, were delivered in less than a week to 2nd Amendment Arms and Ammo in Katy, Texas, a preferred Bud's FFL who charges only a $10 transfer fee per gun with a Texas License to Carry and $20 per gun without the TLC.)

Our first test rifle was a Ruger American Rimfire Standard 8305 22 LR, $309. Ruger's American Rimfire line is already extensive, and new models will build it out further. The 8301 is similar to our test 8305 model, with the former having a barrel length of 22 inches rather than the 18-incher on our rifle. Other 22 LR chamberings in the line include the 8351, which has an 18-inch stainless tube; the Talo Distributor Exclusive 8331, which comes with a Muddy Girl Camo Synthetic stock; and The Shooting Store Distributor Exclusive Model 8334, which has an OD green synthetic stock that contrasts with the black comb modules. Other chamberings include 17 HMR (Model 8311 with a 22-inch barrel; Model 8312 with an 18-inch barrel) and 22 WMR (Models 8321 and 8322, with 22- and 18-inch barrel lengths, respectively).

Our second rifle was the CZ-USA 455 American Synthetic Suppressor-Ready 02114 22 LR, $373. Like the Ruger, the CZ 455 02114 is part of a sizable line of rimfires offered by the Kansas City, Kansas-based importer. Among the other offerings in the 455 line are the CZ 455 American Combo Package, which comes in 22 LR and also ships with a 17 HMR barrel, along with everything you need to make the caliber change. Other interesting models include the 455 American Stainless, which comes with a swappable 20.5-inch barrel finished in a matte bead blast. For those of you who don't foresee ever buying a suppressor, the American Synthetic is similar to our test gun but is not suppressor-ready. The price difference is so small, $421 for the threaded rifle and $385 for the non-threaded barrel, we don't see the value in the threadless version.

The third rifle was the Savage Arms MKII FV-SR Threaded Barrel 28702 22 LR, $248. The shooter may wonder if the $248 price suggests that this rifle is cheap. It is inexpensive, but not cheap. One example of value was the receiver-mounted Picatinny top rail, which allowed us to pop on a Nikon scope with ease and bore-sight the rifle in minutes. Very handy. Also, there's the adjustable AccuTrigger, which came out of the box at 2.4 pounds.

July 2018 Short Shots: Rifles and Rifle Accessories

Brownells recently rolled out the BRN-22 Receiver for custom rimfire rifle builds. The BRN-22 is fully compatible with the popular Ruger 10/22, so you can choose from the many barrels, stocks, triggers, and other custom components for the 10/22 platform. According to the Brownells website, the BRN-22 receivers are machined from 6061 aluminum billet "to exacting tolerances." Brownells touts the machined receivers as better than forged, and points to the smooth, clean interior "to realize that a machined receiver can be held to much tighter tolerances for a precise fit with other parts." After machining, BRN-22 receivers get a matte-black Type 2 hardcoat anodized finish.

Rifles Ready for All 50 States: Springfield, Troy, and Uintah

Innovation in firearms design has always meant finding a way to make guns more accurate, more reliable, less expensive to produce, and for the end user, easier to operate and maintain. And when it comes to trying to satisfy the restrictive demands of different state laws, the word innovation can once again be applied. Naturally, we'd like to see talented people work toward solutions without so much regulation, but we also wondered if makers seeking ways to satisfy the legalities of certain policies, a better firearm, or at least a promising new design, would emerge.

For insight into the world of regulated firearms manufacture and sale, we visited Todd and Amy Arms & Ammo in Petaluma, California. A family-owned full-service gun store run by retired Marine Todd and his wife Amy, their bustling shop serves as the epicenter of gun goodies in the more-gun-friendly area of Northern California. At Todd and Amy's, we learned that several inventors have been tackling the problem of providing workable solutions to producing 50-state-legal long guns for some time, including fixed magazines, variations on the pistol-grip stock, and even pump-action designs. In this test, we will look at three production rifles that incorporate elements of AR-type-restricted design found in states such as California, New York, Maryland, New Jersey, Illinois, and others. Because of constantly changing laws in these states, you must know your local regulations to see if a particular rifle conforms to your state's regulations. We do not guarantee these firearms will remain legal to own in any state, so check before you buy.

Our first choice was the $1135 CA Compliant "AR-15" Saint from Springfield Armory chambered in 5.56mm/223 Remington and featuring a full-float barrel.

Next was a pump-actuated "AR-10" from WorldofTroy.com chambered in 243 Winchester. List price of the Troy Pump Action Hunting Rifle was $899.

Our third test gun was a full-length bolt-action rifle from Uintah Precision chambered for 6.5 Creedmoor. Why is a bolt-action rifle in this review? Because the threaded barrel, upper, and handguard are configured as an AR platform that was designed to fit an AR-10 lower. Uintah sells the upper alone for $1295, but they were able to supply a matching lower so we had a complete rifle for our tests. Therefore, in the Uintah's specifications chart, the term "as tested" denotes measurements taken for the upper receiver only, as your lower may vary.

For ammunition supply we relied heavily on new selections from Black Hills Ammunition. Black Hills is a family-owned business that came to prominence by developing a 223 Rem. load topped with Sierra's 77-grain bullets for the U.S. military, therefore vastly improving the stopping power of the select-fire M16 rifle and its semi-auto civilian-version AR-15. Our Springfield Cal-legal Saint was stoked with four different rounds manufactured by Black Hills ammunition, ranging in bullet weight from 60 grains to 77 grains. Much of Black Hills production still relies heavily on military contracts, and this stamp of approval is why we so often favor their ammunition.

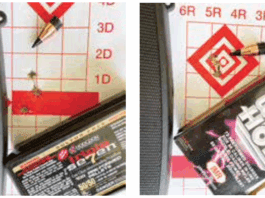

Black Hills has lagged noticeably behind other makers in offering 6.5 Creedmoor (or 6.5 CM) commercially, and now we think we know why. As of this writing, it has been announced that SOCOM, i.e. USSOCOM (Special Operations Command), is evaluating chambering 6.5 Creedmoor and phasing out the use of 7.62x51 (308 Winchester) ammunition in AR-10-type rifles. The Uintah rifle was fed Black Hills 143-grain and 147-grain ammunition, plus 140-grain rounds loaded by Hornady. Our pump-action Troy rifle was treated to three rounds from Black Hills Ammunition, each topped with Hornady bullets. The 243 Winchester ammunition featured Hornady's 95-grain Hornady SST, 80-grain GMX, and 58-grain A-Max bullets.

To ensure that our rifles had the benefit of high-grade optics, we relied upon the Nightforce ATACR 5-25x56mm SFP Enhanced riflescope (No. C554), featuring 0.10 Milradian click adjustments and extraordinarily clear glass. The reticle was illuminated by pressing the button at the center of the parallax adjustment turret, but "Enhanced' might very well refer to the interaction of the big, bold reticle constructed with fine lines, maximizing the capabilities of second-focal-plane design. Overall construction was robust, but relatively compact. We also tried out the Nightforce SR 4.5x24 Competition riflescope designed for the High Power Service Rifle division when it occurred to us that the California Legal Saint AR-15 may be the gun of the future for competitors in California.

Threaded-Barrel Bolt Guns In 300 Blackout and 308 Win.

A few years ago, the incidence of factory-supplied threaded barrels on rifles was negligible, because most people didn't have a lot of interest in changing their muzzle devices, including flash suppressors and sound suppressors. Sound suppressors, also incorrectly known as silencers, and more accurately called "mufflers" or "moderators," just weren't that common because the devices were regulated by the National Firearms Act (NFA) of 1934. In that law, Congress used its tax power to set up a tax-and-registration system for machine guns, short-barreled shotguns and rifles, grenades, mortars and various other devices, including sound suppressors.

Under the NFA today, a prospective owner must go through a months-long registration process with the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (BATFE) and pay a $200 tax, in advance, before he or she can purchase a suppressor. Despite the difficulties posed by the regulatory system, suppressor sales have continued to grow over the last decade, and especially the last five years. Suppressor ownership is legal in most states. The exceptions are Hawaii, California, Illinois, New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts. In the 42 states where suppressors are legal, they are allowed for hunting in all but Connecticut and Vermont, and states are de-regulating suppressor use every day, so this list may be outdated by the time you read this.

Concurrent with the sales growth of suppressors, manufacturers have responded by making the muzzles of some of their rifles and pistols easier to receive the devices. Thus, the growth of factory-threaded barrels, three models of which we recently tested, with and without a suppressor.