Magnum Revolvers: 6-, 7-, and 8-Shooters from Taurus, S&W

We test three 357 Magnum revolvers with different capacities for personal defense. We liked the Taurus revolvers the best, with the Model 66 and Model 608 hitting like heavyweights. So which won?

Which Cowboy Revolver? We Test Three 357 Magnum Guns

We recently tested three single-action traditional-style revolvers in the popular 38 Special/357 Magnum chambering to find which revolver would be best for Cowboy Action Shooting. We also considered the merits of each as a trail gun. While some may scoff, there are many single-action revolvers in use for home protection, including protecting the homestead against predators, so we had to consider this role as well. The three revolvers were from Traditions Performance Firearms: the Sheriff's Model, the Liberty Model, and the Frontier Model. The qualifying difference between the three revolvers are their barrel lengths, though in this test, they are vastly different overall. The longer the barrel, the greater the weight of the revolver as well. The barrels were 3.5, 4.75, and 5.5 inches long. While we liked the 5.5-inch barrel the best based on balance, point, and fast-paced accuracy, the gun itself was the roughest revolver tested as far as the trigger action went and the only one that gave trouble. It wasn't difficult to get it up and running, but this just isn't welcome in a new revolver. On the other hand, the Sheriff's Model was a fun gun to shoot, but not the most practical. We cannot recommend it for CAS competition, but it makes a good recreational handgun and perhaps even a personal-defense revolver for those skilled with the single action. The 4.75-inch-barrel Liberty revolver was the most accurate revolver and was well finished with beautiful laser engraving. It was more accurate than the longer-barrel revolver from the benchrest but not as easy to get a fast hit with on the action course.

When you choose a single-action revolver for Cowboy Action Shooting, a sense of style and history are important. Reliability and good value are also important. When considering the single-action revolver, the 7.5-inch barrel length is regarded as too large and heavy by most shooters. A shorter-statured shooter may find the muzzle in his boot tops in a conventional holster. The fit, finish, and barrel length and balance, then, are important. For recreational use, one may be as good as the other. The greatest accuracy, velocity and handling advantages are more important in a handgun to be used in CAS competition. Considerations other than accuracy, such as heft and fast handling, are important. The speed of the draw is important. The so-called Tall Draw with a long-barrel revolver isn't as fast as with the shorter handguns. This fact gave birth to the original SAA that came to be known as the Gunfighter's barrel length. The barrel was cut right to the ejector rod, and this resulted in a 4.75-inch-barrel revolver. The compromise 5.5-inch barrel length was often called the Artillery revolver and issued to cannoneers. The short 3-inch-barrel revolver was called the shopkeep's or, more popularly, the Sheriff's Model. We tested all three to determine which has an advantage.

The caliber wasn't difficult to choose. While the 45 Colt, 44-40 and 38-40 may be more authentic to the time period, the 38 Special is the superior cartridge for competition today, we believe. The larger calibers are sometimes smoky when downloaded. The 38 Special responds well with Cowboy Action loads. If you desire, the 357 Magnum cartridge may be loaded for use as a trail gun or as a defensive handgun. Anyone who uses the SAA revolver well in CAS competition would be a formidable opponent in a home-defense situation.

For ammunition, we chose three loads, one in 38 Special and two in 357 Magnum. We used a handload consisting of the Magnus cast bullets 200-grain RNL ($49.10 for 500 bullets from MagnusBullets.com) and enough Titegroup powder for 720 fps. This is an outstanding load with plenty of bearing surface for accuracy. It hits the steel plates hard. Next, we used the Black Hills Ammunition 357 Magnum 158-grain cowboy load ($30.30/50 rounds from AmmunitionToGo.com). Loaded to 805 fps on average, this load offers the ease of loading of the full-length Magnum case but is loaded to 38 Special velocity. Finally, we used the Federal 125-grain JHP as a general-purpose 357 Magnum load to determine how the pistols perform with Magnum loads. It costs $21.30/20 rounds. While Cowboy Action guns are seldom fired with full-power ammunition, for Gun Tests, Magnum loads were an important part of the evaluation equation.

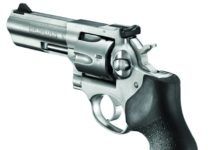

Double-Action 357 Magnums: Ruger & S&W Revolvers Tested

Among the most popular revolvers is the double-action 357 Magnum, and shooters can confirm this because Smith & Wesson recently reintroduced the Combat Magnum and Ruger has introduced a seven-shot GP100 357 Magnum. Those companies wouldn't (purposefully) add a couple of dogs to their inventories. Shooters like the 4-inch 357 configuration because these revolvers make for excellent all-round hunting, personal defense, and target guns. Some revolver fans also favor them for concealed carry. Also, they will stand up to long-term storage and come up shooting. It is interesting that a number of special teams in Europe and the U.S. Military keep the 357 Magnum in inventory for this reason.

Readers have asked us to revisit the category with an eye toward picking a used wheelgun that could save them a couple hundred bucks — that is, they wanted us to go bargain hunting. So we purchased a quartet of used revolvers from major brands that included adjustable sights with 4-inch barrels capable of serving for some types of hunting and for home and auto defense. In other words, we wanted the best go-anywhere do-anything revolver, not a specialized concealed-carry type, such as the Ruger SP101. The 357 Magnum is a great defense cartridge and also a fine pest and varmint round in accurate handguns. With the proper loads, the cartridge is versatile and will take deer-sized game at modest distances. Also, a major advantage of the 357 Magnum is the ability of the revolver to chamber 38 Special +P or stouter cartridges, but as important, softer-shooting loads as well. A practice regimen of twenty 38 Specials for every Magnum is recommended by most trainers. We elected to test the revolvers with both 38 Special and 357 Magnum loads and also to include handloads that have proven themselves. Interestingly, the two Ruger GP100 revolvers, one in stainless steel and one in blued finish, showed practically the same firing line and absolute accuracy performance. However, the two Smith & Wesson revolvers, also one blued and one stainless, had considerably different characteristics.

The test firearms started with the Smith & Wesson Model 19 Combat Magnum, $800 used. This particular Combat Magnum came with a display case and a knife with matching serial number — pretty neat, but also pricey. The Combat Magnum name gave way to the Model 19 designation in 1957, the year when Smith & Wesson changed from names to model numbers. It has always sold well with a 4-inch barrel, in either bright blue or nickel finishes. Other barrel lengths have appeared as well, with 6-inch (1963) and 2.5-inch (1966) barrels showing up as mainline production guns. There is also a rare variation of the Model 19 with a 3-inch barrel. The Model 19 was dropped from the line in 1999 as police agencies migrated to semi-autos, but Smith & Wesson reintroduced the Model 19 Classic (4.25-inch barrel) at the 2018 NRA Annual Meetings & Exhibits (Model No. 12040, MSRP $826). There's also a Performance Center Model 19 Carry Comp No. 12039 (MSRP $1092) with a tritium front night sight, custom wood and synthetic boot grips, and a 3-inch PowerPort vented barrel for recoil management. The revolver features a trigger overtravel stop and Performance Center tuned action. We previously tested a less-expensive Model 19-4 nickel-finish variant in the March 2015 issue, giving it an A grade.

Next up was a silver-skinned copy of Model 19, the stainless-steel Smith & Wesson Model 66 Combat Magnum 38 Special +P/357 Magnum, $420. In July 1971 Smith & Wesson announced its first stainless-steel 357 Magnum, the Model 66. Like the blued Model 19, the Model 66 was a favorite of everyday cops who wanted a Model 19 that was rust resistant. The 4-inch-version, like the one we tested, was the most popular. It stayed in continuous production until 2005, when Smith & Wesson dropped the Model 66 at its 66-7 iteration. Then production on the handgun was restarted in 2014, with the 66-8 unit, which is still in the catalog as Model No. 162662, with a suggested retail of $849. In the June 2001 issue, we tested a 2.5-inch-barrel M66, saying of it: "Even with the small problems we encountered, this is a superior weapon, and few revolvers can match this incarnation of the snubnosed K-frame." In the April 2002 issue, we tested a 4-inch Smith & Wesson M66-2, $219. That Smith & Wesson Model 66 was gauged to be in 95 percent condition, which would bring a Blue Book price of $300 at the time. It earned a "Buy It" recommendation.

Taurus Model 66 38 Sp. +P/357 Magnum, $325

When we began testing the 4-inch 357s, we wondered if a longer barrel, such as the 6-inch Taurus 66 357 Magnum, might give us the best of both worlds. It is a K-frame revolver like the Combat Magnum, but a 6-inch barrel might give us good velocity and accuracy. We were disappointed in its performance. Still, we would have got our money's worth for a modestly priced recreational and home-defense revolver.

New Revolvers from Kimber, Charter Arms, Ruger, and Colt

Why are there so many snubnose revolvers being manufactured? There is no sign that big-bore snubnose revolvers are going away any time soon, especially with manufacturers introducing new snubnoses. Snubnose wheelguns have been and are still excellent choices for self-defense sidearms. Easy to use, no magazine to lose, and chambered in powerful calibers, revolvers are here to stay. So we took a look at four new snubnose revolvers: the Charter Arms Boomer, Ruger's LCRx, the Kimber K6s CDP, and the Colt Cobra. These snubnose revolvers all proved to be reliable, safe, consistent, and accurate for self defense. What we experienced with these revolvers was a variety of grip sizes, some of which our testers said were too small for comfortable shooting or they were too big for ideal concealed carry.

The sights on three guns were very serviceable, while one didn't have sights at all. The triggers separated the pack, as did the chamberings. Two used a double-action-to-single-action trigger and two featured a double-action-only (DAO) trigger. A revolver chambered in 357 Magnum offers convenience because it can shoot 38 Special ammo, too. After tallying the scores, in our opinion the Ruger LCRx is a good choice for concealed carry, though we would tweak it. The Charter Arms Boomer, Kimber K6s, and Colt Cobra are all pretty good choices, but as you will see, the devil is in the details on those three.

We tested at 10 yards because these snubnose revolvers are made for concealed carry and short-range encounters. But we learned 10 yards was too far if you don't have sights, so we accuracy tested the Charter Arms Boomer at 7 yards. Not having sights is a liability as the distance between you and a bad actor increases. Though we typically test at 25 yards, FBI data shows that most gunfights between an officer and an attacker occur from a distance of 0 to 5 feet apart. We concealed-carry citizens can expect the same. The reality is these revolvers are made for up-close work. Short sight radii, smallish grips, and DA triggers do not make for tack-driving accuracy.

We also carried these revolvers in inside-the-waistband (IWB) and appendix-carry-style holsters. We took the time to practice our draw and dry-fire these revolvers at an imagined bad actor a few steps away. On the range, we tested for accuracy using a rest. The DA/SA trigger mode on the LCRx and Colt provided an edge over the DAO models. We also tested a variety of ammunition, and the K6s and LCRx proved to be more practical and versatile because they can fire both 38 Special and 357 Magnum cartridges. Here's what we thought about each handgun in more detail.

Good Buys, or Goodbyes? We Test Experienced Wheelguns

Before law enforcement changed over to semi-automatic pistols, most officers carried a 357 Magnum revolver. Though some write off revolvers as the firearms equivalent of rotary phones, many of our staff consider the revolver to be a simple-to-operate self-defense firearm with built-in safeties and no magazine to lose. We also like the 357 Magnum cartridge. In addition to self-defense use, some team members have used the round to hunt medium-size game, so power isn't an issue.

Because a good revolver stands the test of time and usage well, but also depreciates enough to become affordable for more folks, we assembled three used revolvers from what was once the big three of U.S. revolver manufacturers—Colt, Smith & Wesson and Ruger. In general, we would rate the condition of these revolvers from 80 to 90 percent by NRA standards—we could tell they have been used, but we could not see where they had been abused. All samples were chambered in 357 Magnum, and all were designed for self-defense with barrel lengths that ranged from 2.15 inches to 4 inches and double-action/single-action trigger modes. Safeties are built into these three revolvers. The S&W uses a hammer stop, while the Ruger and Colt use hammer transfer bars.

From that starting point, this pack then diverged, with each offering characteristics that ranged from thumbs-down to thumbs-up for our shooters. Some incorporated an excellent grip that helped tame the felt recoil of the 357 Magnum; some were slim and more easily carried concealed, and some were equipped with large, easy-to-align sights.

With any used revolvers, we have a process of testing the chamber-barrel alignment with a range rod, and we found all were aligned. We also check the timing to see how the cylinder rotates in DA mode and SA mode to ensure the chamber is aligned with the bore of the barrel. They were. We also look at the gap between the front of the cylinder and the forcing cone or rear of the barrel. We use a feeler gauge and expect to have .006 clearance. Any less and there is a chance the cylinder may bind after shooting as fouling builds up. Any more and the user might experience splatter from burning gases escaping from the gap. We also look for forward and rearward play in the cylinder when locked in the frame. These revolvers were tight and stood as good examples of the revolver manufacturers' art and science.

We tested accuracy at 25 yards, which pushed the envelope of these revolvers' capabilities, depending on the user. We also found these revolvers had good accuracy. In close-range testing, some of these revolvers could get lead downrange fast and in good groups. Test ammunition consisted of Winchester PDX1 Defender 357 Magnum with a 125-grain bonded jacket hollowpoint, Aguila 357 Magnum with a 158-grain semi-jacketed hollowpoint, and SIG Sauer 38 Special +P, loaded with a 125-grain jacketed hollowpoint.

We had no issues with any of the revolvers. They all performed in DA and SA mode and loaded and ejected empties if we did our part and used gravity to our advantage. We did find that the S&W had the advantage as a concealed-carry revolver, but the Ruger and Colt were quite capable. Here's what we found out about these handguns after the brass cooled.

2016 Guns & Gear Top Picks

Toward the end of each year, I survey the work R.K. Campbell, Roger Eckstine, Austin Miller, Robert Sadowski, David Tannahill, Tracey Taylor, John Taylor, Rafael Urista, and Ralph Winingham have done in Gun Tests, with an eye toward selecting guns, accessories, and ammunition the magazine's testers have endorsed. From these evaluations I pick the best from a full year's worth of tests and distill recommendations for readers, who often use them as shopping guides. These choices are a mixture of our original tests and other information I've compiled during the year. After we roll high-rated test products into long-term testing, I keep tabs on how those guns do, and if the firearms and accessories continue performing well, then I have confidence including them in this wrap-up.

Bisley Revolvers Revisited

In 1894 Colt debuted a target variation of its Single Action Army pistol (SAA) called the Bisley. This new revolver was named after the famous British shooting range in Surry, England. Colt manufactured more than 44,000 Bilsey revolvers in 18 different chamberings, with barrel lengths of 4.75, 5.5, and 7.5 inches, until 1915, when the company discontinued the line. A very small number had adjustable sights, but most had fixed sights like the SAA. The Bisley used the same frame, barrel, ejector-rod system, and cylinder, as well as the basic mechanism of the SAA, but the new gun also offered some distinct differences — namely the hammer, trigger, and grip, which were designed for the late-19th-century target shooter. Some internal parts like the mainspring, hand, racket, and others were also different.

The shape of the Bisley grip is swept under and appears more vertical than the traditional SAA, and that's for a reason: To accommodate a bent-arm single-hand hold, which for today's shooter looks and feels archaic. Obviously, one can shoot a Bisley like any modern pistol by keeping the wrist locked with a one-hand or two-hand grip, like with modern semi-automatic pistols such as the 1911, Glock, and the ilk. But the Bisley's grip doesn't lend itself to this modern hold.

Also, the Bisley's trigger is wider than the traditional SAA, the trigger guard is shaped differently, and the hammer spur was lowered to make it easier to cock without a shooter needing to loosen his grip.

The shape of the Bisley grip is swept under and appears more vertical than the traditional SAA, and that's for a reason: To accommodate a bent-arm single-hand hold, which for today's shooter looks and feels archaic. Obviously, one can shoot a Bisley like any modern pistol by keeping the wrist locked with a one-hand or two-hand grip, like with modern semi-automatic pistols such as the 1911, Glock, and the ilk. But the Bisley's grip doesn't lend itself to this modern hold.

Also, the Bisley's trigger is wider than the traditional SAA, the trigger guard is shaped differently, and the hammer spur was lowered to make it easier to cock without a shooter needing to loosen his grip.

Ruger refreshed the Bisley in 1984, introducing the Ruger Blackhawk Bisley with a similar unique grip, but not as tucked as the original Colt, and with target sights and an engraved unfluted cylinder. The Ruger Bisley grip design allows for less movement of the grip in hand when firing hot loads. Unlike a SAA grip style, which curls up in your hand when firing hot loads, the Bisley transfers the recoil into the palm of the hand, a more comfortable experience when shooting hot loads. A Bisley of one type or another has been in Ruger's catalog ever since.

We wanted to take a look at an old-school Bisley and a modern Bisley to compare them side by side, so we acquired an Uberti Cattleman Bisley, which is a spitting image of an original Colt, and the more modern variant in a Ruger Bisley Vaquero, built on the New Vaquero frame. Our first task was to use a revolver range rod and rod-head combo from Brownells in 38 Special/357 Magnum (080-617-038WB, $40) to check each chamber for alignment with the bore, and we found everything to be in spec. Some older replica revolvers might have had the throat of a chamber opened up to accept a range rod during factory inspection, which means that particular chamber will shave and spit lead and be less accurate than other chambers. The range rod won't pick up this issue.

Handgun Stats: Uberti Cattleman Bisley 346040

If holding to tradition is important to you, then the Uberti Cattleman Bisley has a place in your gun safe. This is a well-made, beautiful revolver that offers good performance at $200 less than the Ruger. The barrel, cylinder, and grip frame are all deeply blued with a rich case-hardened frame color. The smooth walnut grips had nice figuring and were well fitted to the metal.

The blue-blood Colt collectors winced at the Uberti because it was not truly a clone of a Colt, but it was a darned good replica. Small touches, such as the checkered hammer spur, help redeem it in their eyes, though the firing pin was obviously not the cone-shaped firing pin of an original. The Uberti made the same music when cocking as does a traditional SAA. It uses the same type of mechanism, with a half cock notch for loading and unloading. As a result, the Uberti needs to have the hammer rest on an empty chamber when carried.

What was modernized on the Uberti was the elongated cylinder base pin, which has two notches in lieu of one. The shooter can press the base pin screw and push in the cylinder base pin to the first notch to block the hammer from fully moving forward and firing a round. This is not a solution for carrying the Uberti fully loaded, we believe. Instead, we recommend using the "load one, skip one" method like a shooter does with a traditional SAA.

Handgun Stats: Ruger Bisley Vaquero, Model No. 5130 38 Special/357 Magnum, $835

The Ruger Bisley New Model Vaquero offers the unique Bisley look plus many modern refinements that make shooting these revolvers safer and more user friendly. Our Ruger Bisley featured a 5.5-inch barrel, simulated ivory grip, and a polished stainless-steel finish that resembled nickel plating, but with none of the wear and maintenance requirements that finish requires. If the glossy, bright finish has a drawback, it is sun glare when shooting under a clear sky. On the other hand, the stainless finish made it easy to clean the revolver after extended shooting sessions. Testers agreed they would darken the shooter-facing position of the front blade and the semi-circular cutout just to the rear of the groove on the top strap.

The grip is reminiscent of the original Bisley, but it felt more friendly to the modern shooter, in our view. It is not as swept under as it is on an original Colt, so in hand, the Ruger Bisley felt much like a modern semi-automatic pistol. Shot one- or two-handed, the Ruger felt comfortable. We found it delightfully addictive to shoot with mild 38 Special loads, and quite comfortable and easy to manage with hot 357 Magnum loads.

The grip panels were an off-white polymer that looked like ivory. The Ruger medallion was inset in each grip panel. The panels were not flush with the frame like on the Uberti, but the edges were smooth, so no chafing occurred during live-fire testing. In hand, the Ruger had a bit of heft to it — 45 ounces — compared to the 7.5-inch barrel Uberti that weighed 47.7 ounces. The Ruger was a natural pointer that we found comfortable to hold, grip, and cock, due to the Bisley's lowered hammer. Testers did not have to break their grips to cock the piece like with a traditional SAA.

Range Data

To test for function, feel, and accuracy, we tried a variety of standard 38 Special and 38 Special +P loads as well as a 357 Magnum set. What we found was that these old-style revolvers shot well. Across all ammo brands and types, we averaged about 1.5-inch 5-shot groups at 25 yards using a rest. Those older-style sights may not be as easy to use as more modern sights, but with some practice by the shooter, they sure can get the job done.

Depending on what you prefer, you will either like the more traditionally styled revolver or the modern update, but for most of our shooters, the Ruger Bisley came out on top, and you will see why shortly. Here's more on the Bisley match up.

We Test Two Light Snubbies in 45 ACP; One Cracks Up, Fails

Chambering 45 ACP in revolvers goes way back to the early 20th century and WWI. The U.S. military had plenty of 45 ACP ammo, but few of the then-new 1911 pistols, so the solution was to chamber Colt's and S&W's large-frame revolvers in the 45 ACP cartridge. Since then, numerous S&W revolvers, as well as revolvers from other manufacturers, have been chambered in 45 ACP. S&W used its large N-frame to build the Model 25, similar to a Model 29 except chambered in 45 ACP or 45 Colt, often called Long Colt to ensure it's not confused with Automatic Colt Pistol. In fact, the Model 625 is one of the more popular action-competition revolvers. The Governor is another Smith & Wesson revolver that shoots 45 ACP. But neither of these wheelguns are compact enough for easy carry.

Compact is a relative term when describing a S&W N-frame. The N-frame is used for the S&W Model 29 chambered in 44 Magnum and high capacity 8-shot 357 Magnum revolvers like the Model 327, 627, and others. The S&W Model 325PD and the S&W Performance Center Model 625-10 tested here both feature scandium-alloy N-frames, alloy barrel shrouds, steel barrels, and titanium cylinders to cut weight, making their heft suitable for conceal carry. As a result, we found toting these wheelguns in a holster on our hip was comfortable to do, and if they performed as shooters, we would assess them as good choices for defense. Availability is something of an issue, of course, because the S&W Model 325PD is no longer produced by S&W, and the S&W Performance Center Model 625-10 was a Lew Horton Special Edition revolver offered in 2003 and 2004. But we found two that were in LNIB (Like New In Box) condition, and we saw others for sale at various retailers and auction houses in case you're interested.

Moon clips are required to make these N-frames run fast. Clips for 45 ACP revolvers come in two-, three- and six-round clip configurations. We tested these N-frames with three- and six-round clips acquired from Numrich Gunparts Corp. (GunpartsCorp.com). Six-round moon clips (252510B) cost $1.40 each and three-round half-moon clips (252670B) cost $2.25 a pair. We also used a case-removal tool (958390B) that cost $10.65, which is a notched tube that fits over the fired case and is used to twist the empty case out of the clip.

We ran these revolvers using a mix of factory 230-grain ball ammo from Hornady and Winchester, reloads with 185-grain SWC bullets, and a load from a custom ammo reloader in 45 Auto Rim. The custom 45 Auto Rim ammo manufactured by American Custom Ammo (AmericanCustom.tripod.com, acrammo@sum.net, [850] 689-4553) was loaded with a Rainier 200-grain TMP/FN/FB bullet. The 45 Auto Rim cartridge was developed in 1920 as a substitute for 45 ACP and moon clips in M1917 revolvers. These cartridges have a thick rim and headspace on the rim.

Though both of these revolvers shared the same material in their frame construction, they were set up with different grips, barrel length, sights and lock up. Spoiler alert: The 625-10 was a real contender for conceal carry, but a defect caused it to be eliminated from consideration. Here's more about what we found with these 45 ACP snubnose revolvers.