Gun Owners of America issues statement on Arizona shooting

Crimson Trace Announces Laser Sight for Ruger’s LC9

Stealth Cam introduces the new Scouting Camera, $169

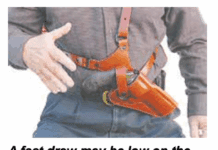

DeSantis Gunhide Introduces New Intruder and Mini Slide Holsters

Bushmaster Thinks It Will Clean Up with Bore Squeeg-E Cleaning System

Videos on GunReports.com!

Rimfire Riflescopes Under $50: Bubbles Sink TruGlo and BSA

Rimfire Riflescopes Under $50: Bubbles Sink TruGlo and BSA

Videos on GunReports.com!

Sabatti 450/400: Affordable Double Rifle, Perfect Caliber

A double rifle for $5500? It can't be very good, we thought, when our neighbor phoned us to tell us he had just bought an Italian Sabatti Model 92 Deluxe rifle, new from Cabela's for that price, in caliber 450/400.

The cartridge is an excellent one for double rifles. It's known as the 450/400 3-inch or the 400 Jeffery. There is also a 3.25-inch version that was originally a blackpowder cartridge, but the 3-inch version was never factory loaded with black powder. It is one of the lower-pressure British cartridges, along with the 470 and 360 No. 2, and thus is an excellent choice for a double rifle, especially if it's to be used in extreme heat. The cartridge was one of the more popular all-around cartridges for hunting use when it was introduced in 1902. Its popularity suffered when the 375 H&H Magnum came along a few years later, but the 400 Jeff throws a heavier bullet, 400 grains versus 300, and some hunters prefer that.

We went to look at our neighbor's rifle, and then arranged to shoot it. What follows are our impressions and observations of what we now consider to be a bargain.

Laser Lightshow: Crimson Trace, LaserMax, LaserLyte Compete

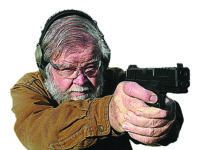

Proponents of laser sights say the electronic devices make it easier and faster to hit a target—on average, a half second to 1 second faster, depending on the shooter. Mainly, the reason is optical: Shooting with iron sights takes effort, since three focal planes need to be aligned: rear sight, front sight, and target. By projecting an aiming point onto the target plan, the laser folds all three sight plans into one target plane. Place the dot on a target at the zeroed in range, and that is where the bullets will hit. Another advantage laserphiles claim is that lasers allow the shooter to hit targets from unconventional or inconvenient shooting positions with ease. And, importantly, laser sights also make good training devices. Dry-firing exercises with the red dots show shooters if they are correctly pressing back on the trigger and not exerting side pressure, or have some other flaw that the jiggling red dot exposes.

Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation, or, laser for short, is a way to emit electromagnetic radiation in the form of visible light. Physics aside, a laser sight is actually a laser pointer on steroids. The FDA regulates laser sights as Class IIIa devices that operate at 1 to 5 mW (milliwatts). Early generations of laser sights were conspicuous bolt-ons. More gadget than gear. Current laser sights are more integrated with firearms. We wanted to test current laser sights to see how they would perform, including ease of installation and use, durability and concealability, so we chose the Crimson Trace LG-401, $329; LaserLyte's RL-19N, $200; and the LaserMax LMS-1911M, $400, as three examples of lasers that operate slightly differently because of how they're fitted to the gun.

Several cautionary notes, however. Lasers can be hazardous. In fact, Crimson Trace instructs buyers to attach a tiny warning label on their firearms before the sight is installed, and it warns about shining lasers in your or other people's eyes, as the rays may damage the recipients' retinas. Also, it's useful to note that a laser can reflect off hard, smooth surfaces. When you hear a bump in the night and activate a laser, be aware of your surroundings. Mirrors, glass, TV screens, and other surfaces will reflect a laser's dot. The reflected light could temporarily disorient you or deflect, looking like multiple lasers. Save the light shows for the concert arenas. Have a plan in mind to illuminate your targets, but not the wife's glass-fronted cabinets. Also, firearms with lasers require additional maintenance. Oil, dust, and other debris on the glass window of the laser's projection port can diffuse the beam. Clean the glass window, and the laser's dot will be sharp and clear. Crimson Trace recommends removing the grips prior to cleaning. Excessive oil can also affect circuitry. Replace the batteries, just as you would with a flashlight. If you use the [IMGCAP(3)]laser sights often, replace them more frequently. And there's the signature debate: the laser may be a deterrent or it may not. A bad guy can see the laser and back off knowing his position is compromised, or if he is determined to do harm, the laser indicates your location.