There has always been a need for a device which will allow easy access to a firearm yet keep it safe from youngsters. The problem can be easily solved by throwing money at it—or by sacrificing quick and easy access to the gun by adults.

In spite of its overprotective and restrictive ways, California passed a gun law that makes sense. How they handle it remains to be seen. The law provides for felony charges against the owner of a firearm who leaves that gun within easy access of a child if that child has an accident with it. (Florida and other states have similar measures on the books.) I think that the law, taken at face value, is a good one, because we all have a moral obligation to see that something of ours isn’t harmful to others.

It has been shown that within a very few minutes of picking up a handgun, a toddler will have it aimed straight at his face with his thumb on the trigger. There’s apparently a natural tendency to look down the barrel; this is just a baby’s way.

The problems with the design of existing handgun locks are the cost of the better systems, the poor looks on collectible firearms, and systems which are relatively easy for 6-year-olds (and teenagers) to defeat. Some of the designs are also awkward, and tend to damage the finishes of high-priced guns. Any one of these reasons is enough to eliminate them from faithful use.

To be effective, the safety lock must reach all the way to the breech; it shouldn’t be easily removed with common tools found around the house; and it must be quickly removable in time of need.

One approach manufacturers have used is making the lock require a manual dexterity that youngsters don’t yet possess. This might work with toddlers, but its not an effective approach with teenagers, who have as much dexterity as most adults.

In my opinion, a unique “key” is the solution to the problem—one which can’t be readily made by a teenager. To prevent a round from being chambered and the gun exploding by accident, the lock cannot block the barrel without also blocking the chamber. Now, if the firearm were to be safe from damage to its finish and could be left loaded and still be safe, we would have all the bases covered.

How to Construct and Install a Gun Lock

Bruce Farmer and I have designed a gun lock that satisfies all these requirements. Plus, it can be made by the average handyman or apprentice gunsmith with very few tools. The easier of the two models put forth here could be made with a drill press, or even just a hand drill and file. The “deluxe” model would be better made on a lathe. A third one, which I have drawn, is better than either of the others, but takes a slitting saw which most people don’t have available. I will explain the two easier locks so that you can make your own decision should you choose to make one. (Actually, there are really more than three models, as semiautomatic pistols, rifles and shotguns would use a chamber-only type, while revolvers would be able to use the through-the-chamber-and-bore type.)

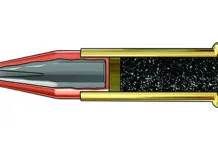

The accompanying drawings really tell the story of the gun lock’s construction, so I’ll simply add some additional instructions that may prove helpful. I used brass for my prototype locks because, being softer than steel, it can’t damage the bore. Brass is also cheaper than stainless steel and more readily available in the sizes needed to approximate the diameter of popular bores. You could probably use a plated metal, but I can’t see going to the trouble when brass will do just as well without that expense.

The size I chose to use for .357 and 9mm bores is .344 or 11/32 inch. This was determined by snugging the minor diameter of a .357 bore with a small hole gauge and measuring the results with a dial caliper. I then subtracted .005 inch so that the same rod stock would be useful for 9mm handguns as well. I would use the same .005-inch clearance for other calibers, since that’s enough to allow easy insertion and the O-ring can easily expand that much under the compression of a 32-pitch thread. An easier calculation would be to try to find some round stock between .008 and .013 inch less than the nominal bullet size for the caliber.

The inside diameter of the O-ring should be from .020 inch under the diameter of the screw used to .020 over. The cross-section of the O-ring should be about 1/8 inch diameter, so that it can be ground to leave a flat surface at the diameter of the gunlock rod.

Tools Needed

You will need most of the equipment listed below, although, with a bit of ingenuity, you might do without a couple of items listed:

●Drill motor or drill press

●Drill bit(s)

●File

●Sandpaper or Scotchbrite pad

●Allen wrench

●Contact cement or “crazy” glue

●Dremel grinder (not absolutely necessary)

I choose the soft stock, either neoprene or other oil-resistant material, with a high coefficient of friction before I do any cutting of the metal. This allows me to know how much to subtract from the length from the muzzle to the breechface. I measure the distance from the muzzle to the breechface, subtract the thickness of the friction disk plus another inch for the section nearest the muzzle. Both ends of this rod must be fairly smooth and perpendicular to the length of the rod. A hacksaw or cutoff tool (in the lathe) are sufficient for cutting the stock, and a file and drill press or lathe tool do well in squaring the ends.

Drill first with a starting drill like a center drill and follow that with a drill of the proper size for the tap you are to use. In a drill press, centering the drill can be a challenge for a beginning gunsmith. This is fairly easy when you know the trick. Chuck up the end of the rod you want to drill, and lower the rod through the drill press vise. Clamp the rod in the vise with the vise free to move on its own, and then secure the vise in the position it finds. Loosening the drill chuck, install a center drill and drill the center of the rod in the vise. The drilled hole should be in the center of the rod.

Drill the tap drill size about 1/2-inch deep and tap the threads in it. I used an 8-32 thread, but a 6-32 socket-head cap screw will suffice for even a .22 caliber, as the head can be thinned down to .177 inch diameter without any trouble. Smaller screw heads have hex sockets too small on which to reliably put security posts. I would really hate to try to drill a hole in a 1/16-inch hex socket and install such a security post, much less try to drill the Allen wrench for the post.

The method of using a washer and not a counterbored section of rod is much easier to do and is just as good. It doesn’t have the professional looks when out of the firearm, but is just as secure as the other. The washer’s outside diameter can be reduced by installing it on a screw with a nut, and then spinning it in a drill press with a file against it. The washer should be filed down to the diameter of the gunlock rod.

Install the O-ring onto the gunlock with the washer or clamping sleeve, and tighten the screw about one-half turn after it starts clamping the O-ring. Reinstall the unit in the drill press or lathe with the breech end in the chuck. While spinning the unit in the lathe or drill press, hold a Dremel tool with drum sander or drum-shaped grinding stone against the O-ring, thereby reducing the outside diameter of the O-ring to the diameter of the main rod. This will, of course, shape the outside to a flatness which will just be what we want. Tighten the screw more tightly and measure the O-ring’s diameter to ascertain that it will put pressure on the inside of the bore. The ones I do easily expand over .025 in diameter with only minimal tightening. This is more than enough to lock the rod into the bore.

The friction pad can now be cemented onto the breech end of the rod and the rod reinstalled in the drill press or lathe. Repeating what we did with the O-ring, we can shape the friction pad to a shape which has the end slightly smaller than the rod end. Now we should be ready to try it for size. Push the rod against the breech with the Allen wrench, and tighten the screw slightly until the rod cannot be pulled out of the barrel by slanting the wrench and pulling. Overtightening could cut the O-ring in such a way that it would prove difficult to remove.

A good variation on this design would be to have the main rod of the gun lock be countersunk on the end and split into several fingers by slitting with a slitting saw back about 1/2 inch. The clamping sleeve would then need a cone-shaped end to force the split fingers out to clamp the bore.

Clean up the gun lock in a suitable solvent which won’t dissolve the cement used for the friction pad. I usually clean the brass rod with either fine steel wool or Scotchbrite pads before cleaning with the solvent.

I have been very careful to avoid using terms which imply absolute security when talking to gun owners, as there nothing completely foolproof in any field of which I am aware. The liberal courts and juries are very quick to award judgments against gun manufacturers and gunsmiths when firearms are involved in accidents. I always point out that there are no absolutes in the real world so each gun owner is ultimately responsible for the decision of whether or not, and how, to use the gun lock.