When it comes to concealing a handgun, there is only so much space available on the hip, inside a handbag, or somewhere else on the body or in clothing. That’s why there are snubnosed revolvers and subcompact pistols. Choosing a handgun, then, becomes a balance of firepower versus weight and overall structural dimensions. In this test, we will limit the size of our test guns to three guns that will fit into a box approximately 5-by-7 inches in size — which represents a handgun that can be carried easily in just about any manner of traditional concealment.

However, we are purposefully mixing apples and oranges, that is, pistols and revolvers, because either design can do the job of self-protection at close range. Our three test guns were the $747 9mm Kimber Solo Carry, the $299 9mm SCCY Industries CPX-2, and the $523 Taurus 40 S&W M405 stainless-steel revolver. Each gun offered at least one advantage not shared by the other two. The Kimber Solo was the most concealable. The SCCY pistol offered the highest capacity, and the Taurus revolver fired the biggest bullet.

The cartridge versus cartridge debate rages on, largely based on the stopping power of one single shot. But let us offer an alternative viewpoint suggested by TacPro Shooting Center’s Bill Davison. Davison, a former Royal Marine and one of the most complete training consultants in the United States, offers that when rating the firepower of a handgun, the amount of energy it can deliver should be the sum of its entire capacity rather than the energy of one lone shot. For example, a 9+1 capacity pistol, wherein each bullet registers about 330 foot-pounds of energy at the muzzle, should ultimately be considered more powerful than a six-shot pistol that fires ammunition capable of delivering 500 foot-pounds with each round of fire. Food for thought.

For our tests, we began by shooting five-shot groups (the capacity of the Taurus) from the 15-yard bench. Then, we applied what we think was a more realistic test. Each gun was fired from a distance of 5 yards at a humanoid paper target. Start position was with the gun lowered to rest on a oil-barrel top about waist high. We used a CED8000 shot-activated timer to provide a start signal and record elapsed time of each shot. We took note of the first shot to see how fast we could get the gun into action and the last shot to see how long it took to deliver two shots to center mass and one shot to the head area. Altogether we recorded five separate strings of fire. We scored the hits A, B, C, or D, looking for ten hits to the preferred 5.9-inch by 11.2-inch A-zone at center mass and five hits to the A-zone in the head, which measured 4 inches long by 2 inches high. The catch was that the test was performed strong hand only. (By a right-handed shooter holding the gun with only his right hand). We weren’t trying to be cowboys or go Hollywood. It’s just that in close-range fighting where guns such as these would most likely be used, applying a support hand may not be possible. On the semiautos, there wasn’t much room for a support hand in the first place.

For testing the Taurus revolver, we chose Winchester 165-grain FMJ ammunition sold in a value pack, Federal Premium 135-grain Hydra Shok JHP ammunition, and Hornady Custom 180-grain XTP jacketed hollowpoint rounds. The 165-grain rounds were also used in our action shooting test. For testing the semi-automatics, we ended up using four test rounds. After testing with 115-grain FMJ, 115-grain JHP EXP hollowpoints, and 124-grain JHP rounds from Black Hills Ammunition, we learned that Kimber had declared that the Solo should only be used with 124-grain and 147-grain bullets. So, we went back to the test range with a supply of Federal 147-grain Federal Hydra Shok ammunition and resumed our bench session. Naturally, we retested the SCCY pistol with the 147-grain ammunition as well. All test rounds were standard pressure, including the Black Hills EXP ammunition, which was designed for maximum performance in firearms not recommended for +P ammunition. Here is what we learned.

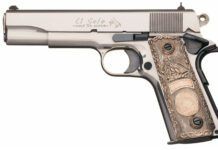

Kimber Solo Carry No. 3900001 9mm, $747

The Kimber Solo Pistol is an alloy-framed single-action striker-fired pistol feeding a 2.7-inch barrel from a six-shot single-column magazine. An eight-round magazine with finger extension ($40) is also available from the www.KimberAmerica.com online shop. Movement of the slide loads the striker spring and resets the trigger. The single-action trigger was hinged from above, and the action, though well defined, could be mistaken for a double-action mechanism. But the intent of the Solo’s design is to afford the ergonomics of the 1911 pistol in a miniaturized product. Another key 1911 feature was the ambidextrous thumb safeties that were held close to the frame and out of the way. Despite their low profile, they were easily operated by the inside knuckle and effectively provided an on/off switch for the pistol. However, the longer swing and aforementioned appearance of being a double-action-only pistol may lead some users to ignore the thumb safeties. Whatever insulation from unintentional discharge there may be, we recommend training to use the thumb safeties.

The visual impact of the Solo was magnetic. Some say it is a reworking of the Colt Mustang, but it could also be considered reminiscent of the Colt Pocket Hammerless pistols. The key is that the Solo was sleek and snag free at every corner and edge. The grip panels were flat and frankly unnoticeable once in the hand. We think the dark KimPro II-treated frame was stealthier than the icy finish of the all-stainless model tested in our May 2011 issue. Indeed, the Solo reportedly has been refined since its initial run.

The stainless-steel slide was topped with a robust set of three dot sights that we found surprisingly visible. The slide offered rear cocking serrations only and an externally mounted extractor. The ejection port was not just generously flared and lowered, but scalloped front and rear along the right side.

Field stripping was simple. Pull back the slide to match the slide-stop lugs with the takedown notch and pull the stop pin free. But unlike on a 1911, the slide was still locked on the frame until we pressed the trigger. With the top end removed, we saw a plunger-style guide rod with the larger forward spring free to butt against the front or yoke of the slide. Kimber probably chose not to capture the front spring so it could be changed regularly without special tools to ensure reliability. Barrel lockup was at the front of the slide, (bushingless) and by a single lug just ahead of the barrel hood. The barrel link was a fixed loop such as found in the CZ design. Once out of battery, the barrel was free to move around quite a bit. The barrel was contoured to save weight. Its low mass helped reliability by requiring less energy to move the barrel in and out of battery.

The bottom side of the slide also revealed a stop lug at the base of the breech face and a heavily made striker stop capping the rear of the slide. We could also see the striker and surrounding spring plus a striker block. Kimber refers to this component, in a mix and match of words, as the firing-pin stop.

We couldn’t help but notice the liberal use of hollow roll pins throughout, including utilization at the ambidextrous magazine release buttons and the trigger hinge. After our first round of tests consisting of about 200 rounds of mostly 115-grain ammunition, we noticed the roll pin above the trigger traveling off center and protruding through the right side of the frame. There was still plenty of pin left in place, and no malfunction occurred. Perhaps this is why Kimber, after initially warning to use only “high quality, factory-fresh, premium personal defense ammunition in the Solo” added a letter of congratulations. This extra page inserted into the shipping box, along with a very nice Kimber logo-emblazed pistol rug and an extra six-round magazine, strongly recommends the use of 124-grain and 147-grain ammunition. The 115-grain rounds rattled the gun pretty good, and the extra vibration may threaten the ability of the pins to stay in place. The letter also states that the Solo was designed to operate with “minimal lubrication.” For our tests, we used a liberal dose of Wilson Combat Ultima-Lube II oil to protect the gun. Based on the amount that ran off and how little wear was detected, we would be comfortable using much less when not involved in long sessions at the range.

The magazines were well made with “feet” that made contact with both the front and rear walls of the magazine. Initially, the magazine release was difficult to operate from either side, but became easier with use. The buttons are big, and you wouldn’t want them to work too easily and suddenly drop the magazine. Empty magazines with the slide locked back dropped freer than loaded ones with the slide closed. We noticed that once a mag was inserted, we were not able to load the chamber unless the slide was already locked back. But from lock back, we were able to use the pinch-pull method or press the slide stop with equal success. Due to the heavy recoil unit and short stroke, it was also difficult to eject a round from the chamber with enough gusto to flip it out of the ejection port. With the magazine removed, most of our rounds fell through the magazine well. Ejecting a round in the event of a malfunction might be a problem. For this reason alone we might shy away from using the 147-grain JHP rounds, as they tend to be longer overall than 124-grain hollow point ammunition. (By about 0.020 inches, according to the Hodgdon Powder No. 27 Data Manual.)

From the bench the Solo did transfer a fair amount of shock but not a lot of muzzle flip. The Solo’s trigger made shooting easier, and we found that our best groups were shot when we used a neutral rather than a vise-like grip. Another trick was to not put too much finger on the trigger. The pad rather than first joint of the index finger was the best point of contact. The Solo displayed equal performance with each test round. Average group size measured about 1.7 inches across with every one of our test rounds, save the 147-grain ammunition. Firing the Federal 147s, average size group was 2.1 inches across, but they were arguably the most comfortable to shoot.

Compared to our best shots with the SCCY pistol, we didn’t necessarily find that the Solo was vastly superior in terms of accuracy. But optimum accuracy was easier to achieve with the Solo. In fact, we thought shooting good groups was hard to avoid. In our action test, we would rate the Solo number one. First shots were gone at little more than 0.80 seconds. Our first total elapsed time was 2.03 seconds, but our last two were 1.95 seconds and 1.90 seconds, respectively. Shots to the midsection scored nine A’s and 1 C (the zone immediately surrounding the lower A-zone). The head showed two A’s and three B’s, with the B-zone being the secondary zone in the head area of the target.

Our Team Said: Other than excess vibration that could loosen roll pins, we’re not sure what all the fuss is regarding bullet weight. It had just about everything you could ask for in a hide-out gun. The Solo indexed quickly into the hand and onto the target. A natural point, sights that you could use when you need them, and a trigger that didn‘t demand a perfect grip for effective control made it easy for us to excel in our close quarters test.

SCCY Industries CPX 2 (Gen 2) 9mm, $299

Very few guns retail for less than $300, so we first had to wonder if this was really a cheaply made gun or if the price was the result of proven methods and materials, unencumbered by expensive research and development. We think the latter.

Some may refer to this pistol as a variation on the Kel-Tec design, and like the Kel-Tec pistols, the CPX-2 is made in Florida. But the SCCY Industries CPX-2 is a second-generation pistol intended to be an improvement over an earlier version (the CP-2). The CPX-2 varies from the CPX-1 in that the former does not have a thumb safety. Instead, this polymer-framed hammer-ignition pistol relies on a long stroke with moderately heavy trigger pull to defend against accidental discharge.

The CPX-2 seemed to deliver more than advertised. We were able to fit and fire 11 rounds from each of the 10-round magazines, which offered a finger-groove basepad to finish the grip profile. Two flat basepads that enhanced concealability without reducing capacity were also supplied. We found the grip comfortable not only because of the “recoil cushion” of the ventilated backstrap but because the grip was reasonably slender and square. The front strap offered finger grooves, and the remaining sides were covered with a knurled pattern. The magazine release was big and square. The slide release was oversized, consisting of a metal tab with polymer overlay. The slide had stylish rear cocking serrations and three-dot sights. The rear unit was windage-adjustable by drift, and there was a locking screw to secure its position.

Removing the top end began with clearing the magazine and the chamber. With the slide locked back, the disassembly pin was aligned with the takedown notch. The owner’s manual recommends prying it loose with a flathead screwdriver. Our first concern was not to mar the slide’s finish, but we found we could pry it out with a thumbnail. The disassembly pin also served to anchor the loop-style barrel link very similar to the one found in the Kimber Solo. We weren’t sure how comfortable we were with the disassembly pin/barrel link pin being so easily removed. But since the pin sat flush with the frame, it wasn’t likely to be accidentally bumped out of place. We did not experience any malfunction that could attributed to this component. The only tricky part of reassembling either of our pistols was making sure the slidestop/disassembly pin was properly threaded through the barrel link.

Recoil was controlled by a steel guide rod with two coil springs captured over its length. The top end was connected with the polymer grip frame by a 7075-T6 aircraft-grade heat-treated aluminum-alloy receiver topped with continuous-length rails measuring about 3.3 inches long beneath the 5.3-inch long slide. The firing pin was deeply recessed from the rear of the slide. The hammer was inboard so it could not snag clothing or otherwise be interfered with. But we could deliver blow after blow without reset by movement of the slide.

At the range we found that trigger finger fatigue was the main problem when shooting groups. The trigger press weighed in at about 8 pounds versus the advertised 9 pounds of resistance. Since the trigger stroke was so long, we thought taking a couple of pounds off the press would probably not make the gun less safe. But we wondered if that would adversely effect ignition.

By taking our time between shots, we were able to produce five-shot groups measuring less than 2.0 inches across with each one of our hollowpoint rounds The SCCY narrowly topped the Solo firing the Black Hills EXP ammunition and produced five-shot groups that averaged about 2.3 inches across firing the Federal 147-grain ammunition. The 147-grain rounds matched up well with the sights of the SCCY pistol, producing groups closest to point of aim.

In our action test, we fired the drill one handed and learned that it took more concentration to stabilize the gun over the course of the trigger press. First shots elapsed time ranged between 0.98 seconds to 1.02 seconds. Total elapsed time also registered inside a narrow range of 2.34 seconds to 2.46 seconds. The score on the lower portion of the target read eight A’s and two C’s. The head area registered one A, three B’s, and one miss. There were no malfunctions.

We decided to try the action test again, this time holding the CPX-2 in two hands. First shots immediately dropped to about 0.90 seconds. Overall times dropped to an average of about 2.09 seconds, but we suspended the two-handed testing when the gun began to lock back prematurely. We tried alternate holds and found two-handed shooting was less reliable unless we made an effort to hold our support far away from the slide latch.

We ultimately determined that the slide latch was vulnerable to being activated by incidental contact for two reasons. First, the detent spring that kept the latch in its down position was very light. Second, the latch was just too bulky and easily hit. We’d recommend a heavier detent spring. But it might be enough to simply remove the polymer overlay on the slide stop and leave just the bare metal tab underneath.

Our Team Said: The CPX-2 may still be a work in progress, but with two or three simple modifications, it could easily be the bargain of the year. Ten, or rather 11, plus one firepower in a small, lightweight package that retails for less than $300 sounds good to us.

Taurus M405SS2 Revolver 40 S&W, $523

The configuration of the Taurus M405 SS2 can be read from its name. It’s a 40 S&W 5-shot stainless-steel revolver with a 2-inch barrel. The pistol round demands the use of moon clips to provide the proper position or headspace in relation to the breech face and firing pin. Does this make it a modern firearm? No, not really. Moon clips holding six rounds and half-moon clips holding three rounds apiece inside a thin spring-grade steel bracket is an invention almost as old as the hand-eject revolver itself. Then again, semi-automatic pistols are more than one hundred years old, too.

The appeal of a revolver over a semi-automatic handgun may be limited due to lesser capacity, but here is a list of wheelgun advantages. First, statistics show that civilian confrontations do not require a high round count. When was the last time a confrontation listed in “The Armed Citizen” column of an NRA publication reported that either party had to reload their weapons?

Next, consider that leaving a revolver loaded for a long period of time has no affect whatsoever on its ability to function. Also, a revolver will fire any type of ammunition of any velocity ranging from a plastic domed load of snake shot to solid lead bullets or any type of frangible you can name without worry of malfunction.

The Taurus M405 revolver is available with either a blued-steel or stainless-steel frame. Features include a ribbed-rubber one-piece grip that attaches from the bottom of the butt frame. There was a wide spur hammer with integral locking system that cannot interfere with hammer movement unless activated with the supplied key. The rear sights consisted of a frame notch with diffuser gap. The ramped front sight was integral with the barrel shroud. It was grooved perpendicular to the bore to prevent glare. We found this rugged design was easy to see even in bright light. The cylinder latch was reshaped to let spent rounds pass easily from the cylinder, and its contact surface was checkered. The cylinder was fluted and the ejector rod was full length ensuring the ejection of spent cartridges. With cylinder closed, the ejector rod was protected inside a long notch that ran the length of the full underlug barrel. There was a spring-loaded detent on the crane that locked into the frame to increase strength of lockup. The tip of the ejector rod did not take part in locking up the cylinder. But it was capped with a finely checkered knob to ensure comfortable, positive operation. The trigger was wide and smooth, and the gun could be fired continuously double action or single action only by manually pulling back the hammer.

Taurus calls the moon-clip system Stellar Clips. That’s okay with us. Lunar Clips makes more sense, but whatever. To load the M405, you had to first load the clips by pressing each round into place. Here’s where you become aware of the difference in case dimensions specifically at the rim. The Winchester cases were hard to get on and off, but the Federals were almost loose enough to fall off on their own. The Hornady cases were somewhere in between. Once the clips were loaded, you had to push all five rounds into place and make sure the center of the clip was all the way down against the cylinder. Once the rounds were fired, the empty cases were ejected together along with the clip. Removing the spent shells from the clip can be accomplished by hand or by using a special tool. Where necessary, we just stuck a piece of brass tubing of slightly less diameter into the mouth of the empty shell and pried them off the clips.

If you have ever seen revolver shooters on the Practical Shooting circuit, you’ve seen moon clips. Tuned competition guns accept and release moon clips holding up to eight rounds almost like magic. The Taurus clips weren’t nearly as fluid, but a little polishing of the clips around the center where they touch the ejector rod would make them a lot faster and more efficient. It would also help to chamfer the chamber mouths. Chamfering changes the angle of the chamber mouth from 90 degrees to as much as 45 degrees, creating a funneling effect. This is not an expensive modification, about $40 on average, and we’d like to see revolvers with chamfered cylinders as standard equipment.

After a few shots single action only from the bench, we thought maybe we were cheating. But if you have the time to take a careful shot, pulling back the hammer manually is a viable option. In fact, we have found that even standard-production revolvers offer a single-action press superior to most semi-automatic pistols. The results showed a 0.8-inch group firing the Winchester 165-grain FMJ rounds leading the way to a 1.0-inch average size group. The 135-grain Federal Hydra Shok rounds were less accurate but produced almost 400 foot-pounds of muzzle energy. Our favorite load was the Hornady 180-grain XTP hollowpoints because the Taurus was dead on in terms of point of aim/point of impact. Resulting groups ranged in size from 1.1 inches to 1.5 inches across. To compare the effects of single-action versus double-action fire, we tried repeating our benchrest session shooting the Hornady ammunition double action only. The Taurus double-action trigger was smooth, but once we began our stroke, the trigger seemed to multiply the action and take us through the shot. When we fired the 405SS2 double-action only from a rest, our groups ranged in size from 1.2 inches to 1.8 inches across. Calculating our Hornady groups, the actual average was 1.35 inches single action versus 1.375 inches double-action only — effectively no difference.

Firing a revolver in our action test was very different than firing either of our pistols. As we moved to our first target we were able to roll the cylinder and prep the trigger with more vivid control than we could with either the single-action Solo or the SCCY pistol. First shots ranged from 0.73 seconds to 1.01 seconds. But our overall elapsed times for each run suffered due to the greater recoil of the heavier 165-grain bullets. Average total elapsed time was about 2.50 seconds. We think we could have done better with one easy fix. The ribbed rubber grips were great from the shaded bench. But downrange in the afternoon sun, our hands were sweaty and the ribbed rubber grips caused the gun to swim in the shooter’s hands. A proper wooden grip (of which there are several available) would have helped us tame recoil, reduce elapsed time, and improve our score. Target points were five B-zone hits to the head with five A’s, three C’s and two D-zone shots below.

Our Team Said: With a change of grip and minor refinement, the M405 would be a fine tactical weapon. We could have chosen more radical ammunition without worry of malfunction. The larger-diameter projectile makes this gun a formidable choice.

0712-CONCEALED-ACC-CHRONO-PART-2.pdf