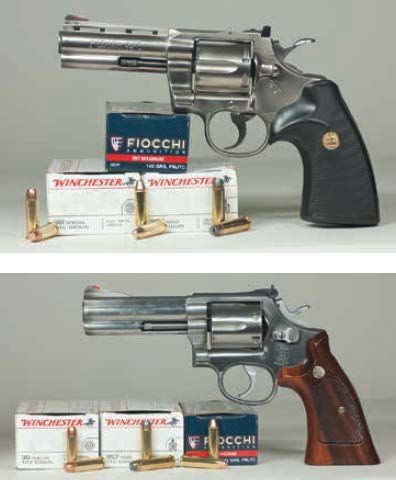

Revolvers changed the firearms world when Samuel Colt introduced the first true production model revolver available to the general public. Since then they have been surpassed by semiautomatics in capacity and overall use, but when it comes to reliability and staying power, can you really beat a classic wheelgun? In this test we look at two revolvers head to head that are considered by some to be the best available: the Colt Python and the Smith & Wesson Model 686-2.

We chose these two for a range of reasons, but the overriding motivation was fun. We believe most people who are purchasing these kind of revolvers are doing so for collecting and shooting entertainment, especially the Pythons, but there is the issue of availability as well. Our FFLs tell us that distributors are sold out of nearly everything but bolt-action rifles. Even single-action cowboy-style revolvers are sold out. People are buying whatever guns they can find, so with supplies tight and prices high, many are using their dollars to invest in iconic wheelguns, just like collectible Fords or Chevys.

We also wanted to look at these pistols on a value basis. The Python is widely regarded as one of the finest production revolvers ever made, and our testing here reconfirmed that. But that quality comes at a price, as Python sales figures continue to climb. When we tested this gun in 2000, a year after its termination, we priced it at $595. A recent check of concluded sales at GunAuction.com showed a pristine blued 1981 Colt Python 357 Magnum 4-inch barrel at a high of $2005 and a low of $995 for a blued gun in Very Good condition. Another blued gun in Very Good condition went for $1212, and an Excellent blued sample went $1799. A factory nickel finish sold for $1507. One gun like our test Python in matte stainless steel sold for $1299 on GunAuction. We found a GunBroker.com auction for one in near-mint condition that sold for $3025 (#327961477). Current “buy it now” prices on GunBroker range from $2000 to $3000. We’d rate the buttery action and low wear on our test gun as at least Excellent. FFL Kevin Winkle has our test gun up for sale and says the first $2500 or best offer will take it. It comes with the factory letter. A factory letter from Colt ($75) tells what the year of manufacture was, dealer it was sold to, and finish, barrel length, etc., so authenticity can be verified.

The 686 (no dash) was introduced in 1980 as the S&W Model 686 Distinguished Combat Magnum Stainless. It featured a flash-chromed forged hammer and trigger and had a six-shot cylinder. The -1 (1986) introduced the floating hand, then an “M” recall (1987) for the no-dash and -1 guns fitted a new hammer nose and firing pin bushing to deal with some ammo causing cylinder binding when fired. The -2 (1987) incorporated the “M” recall features as standard production. Like other 686-2s, our stainless six-shooter is built on S&W’s excellent L-frame with a full-lug barrel. It has a hammer-mounted firing pin, which means it’s a pre-lock design, has no MIM parts, and has its original Goncalo Alves flared wood grips. Those grips have minor chipping along the edges, and there are faint turning marks on the cylinder and not much else wrong. Winkle said he would want $900 for it if he were selling it, which he is not. That’s in line with Gunbroker buy-it-nows ranging from $700 to $900.

Also, these guns are no slouches when it comes to personal self-defense. The revolver offers an on-demand choice of single or double action, it will run reliably on any load strength, and the 357 Magnum guns will also shoot cheaper 38 Special rounds to boot, mixing power and affordability, given normal ammunition pricing. Also, hung with a 4-inch barrel, they offer good sight radius and plenty of power. In sum, for many Gun Tests readers, they’re just right for car or home defense.

So we’ll give away the ending and say that if money were no object, we’d buy the Python. But for most of us, money does matter, and the 3:1 dollar ratio between a Python and a Smith is a lot. Essentially, the question that has to be answered is, Would we be willing to settle for the Smith & Wesson? Read on to find out.

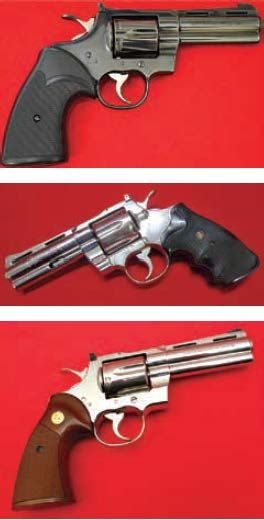

Colt Python 357 Magnum (1988), $2500

The Colt Python is a 357 Magnum caliber revolver formerly manufactured by Colt’s Manufacturing Company of Hartford, Connecticut. It is sometimes referred to as a Combat Magnum. Introduced in 1955 and discontinued in 1999, the Python was available in 2.5-, 3-, 4-, 6-, and 8-inch barrels with blued, stainless, or nickel finishes. The 6- and 8-inch barrels were marketed as target pistols, and one model even came with a 2x scope. As Colt’s top-of-the-line model, it was originally intended to be a large-frame 38 Special target revolver — thus its precision adjustable sights, smooth trigger, full barrel underlug to dampen recoil, and a ventilated rib to disperse heat.

For this test we had a 4-inch stainless Python with black rubber grips. This gun had a tight lockup and lacked endshake. Pythons are always tight because of their hand-to-ratchet construction. On most revolvers, the hand turns the cylinder until it indexes into the timing slot. Pythons have an extra mechanism, a second hand, that catches and holds the cylinder in place. When the revolver is at full cock, just as the trigger is pressed, the cylinder locks up for the duration of the hammer strike. Other revolvers have a hint of looseness even at full-cock. The gap between the cylinder and forcing cone was very tight, further aiding accuracy and velocity.

When trying a used revolver, we check bore-to-chamber alignment with a range rod. Range rods come in two varieties, service and match grade, and both are available from Brownells catalog. We chose the match-grade rod combo ($40, #080-618-138) for our test, and over 12 insertions, we never once found the cylinder and bore out of line. We also noted tolerances that connect the yoke to the frame were very close, yet worked without binding. While there is no detent lock up at the yoke or frame, the width of contact area between these two parts is substantial.

The Colt Python featured a full lug barrel with shrouded ejector rod and vented rib. Unlike most revolvers, the cylinder of the Python rotates clockwise, and down the barrel, we saw a six-groove left-hand 1:14 rifling twist. This varies from the Smith, which we measured to have five grooves with a right-hand twist in 18.75 inches. The barrel was polished to a mirrored smoothness. Reportedly, the bore diameter tapers by 1/1000 inch toward the muzzle, forcing the bullet deeper into the rifling.

To release the cylinder, the shooter slides the latch toward the rear, not forward. Even when the cylinder is swung away from the frame, we noticed no play. The trigger face is narrow with a deep arc and three serrations. The target-style hammer presents a wide checkered surface from which to cock the action. Hard-rubber Pachmayr Presentation grips, which feature checkering but lack finger grooves, finishes the gun in stark contrast to its matte-stainless appearance.

The gun’s 2.9-pound heft along with this simple but effective grip make this gun comfortable to shoot, our testers said. In terms of combat use, we think other guns can learn a few things from the Colt Python. The hard-rubber grip isn’t tacky and it lacks finger grooves, which can actually inhibit a good grip. Finger grooves can make it harder to correct a wrong grip. We have felt lighter actions on Pythons before, but even with minor trigger stacking, we found we could fire this gun rapidly.

The Colt’s front sight blade (a serrated ramp) is double pinned into place. The rear sight is adjustable for windage and elevation, and the delicate blade that contains the notch is housed within a sturdy frame to protect it — a plenty strong and durable combat-ready two-way adjustable sight. The Smith & Wesson sight was somewhat exposed, but to our eyes it seemed well shielded and well anchored.

The Python shot more consistent groups at 15 yards than the 686, averaging 3.9 inches with a 2.9-inch smallest group and a 4.5-inch largest group, both of which came with the Fiocchi 142-grain FMJTC 357 rounds. The Python bested the 686 for average, but not the smallest group, so our testers decided it was pretty much even going into the double-action test.

For this test we started with a standard silhouette target at 5 yards, loaded the revolver with three rounds, then from low ready, we fired two rounds at center mass and one round at the head as quickly and accurately as we could.

This test is where the Python won, mainly because the slightly smaller rubber grip was easier for our testers to control when quickly firing three 357 Mag. rounds. The white U-shaped highlight on the rear sight made reacquiring the sights fast and easy, and the grooved trigger with a defined edge was smooth and easy to pull. We were slightly slower with reloads at first, having to get used to the release being a pull not a push mechanism, though by the end of the test it was no issue. The casings ejected cleanly, we had no malfunctions switching from the 357s to 38s regularly.

Our Team Said: Overall, the Python is an excellent revolver, and although prices for them are steep, true revolver aficionados should start saving up to buy one of these classics.

Smith & Wesson Model 686-2 357 Magnum, $900 (1988)

We chose a 686 of comparable age to the Python, although Smith & Wesson offers newer models of the 686 that addressed some of the faults we found with our handgun. Overall, the Model 686-2 is a great revolver.

The L-framed model had a heavy, full-lug barrel, shrouded ejector rod, relieved cylinder latch, and original Smith & Wesson wood grips with exposed backstrap. The finish was a natural-buff stainless steel.

The stainless-steel frame and barrel and checkered wood grips came together for a classic look. The 4.1-inch barrel was slightly longer than the Python’s, and the wood grips were considerably larger, with a lot of flare at the bottom. Our 686 was slightly lighter than the Python, but it too weighed well over 2 pounds, so an ounce difference didn’t really matter.

Sights were a stainless front ramp and stanchion machined into the barrel top with an orange serrated insert. The rear sight was fully adjustable, but it lacked a white-outline notch like we saw on the Python. Almost the entire top of the barrel was serrated along its length, providing a glare-free surface. The hammer spur was smaller in both in height and width than the Colt’s, and the trigger was moderately wide, rounded, and smooth.

The Smith & Wesson double-action trigger presented the shooter with excellent feedback by way of two distinct clicks. The first click occurred with about a quarter-inch of rearward movement, then we could hear another click when the hammer was drawn fully back. That corresponded with the trigger being positioned almost all the way to the back of guard. This made firing predictable every time. There was clean, motion-free movement of the trigger when fired single-action. Checking bore-to-cylinder alignment with the Brownells match-grade range rod showed no chambers out of time. Smith collectors praise the earlier 686 models because there are no MIM parts and the hammer-mounted firing pin makes direct contact with the primer, rather than the hammer striking a frame-mounted pin like the Python’s. There’s also no transfer bar safety.

During bench tests, our testers said the 686’s larger grips were a little unwieldy when shooting the 357 rounds, shooting as large as a 6-inch group with the Fiocchi cartridges, but we tightened things up with the 38’s and shot as small as a 2.2-inch group. Once averaged, the groups came out at 4.1 inches, which is just a two-tenths inch difference from the Python. Also, the Smith shot the smallest group all day, so we call the accuracy trial a tie.

The flaws we found with the 686 came during our double-action test. We found the larger grips were just too big and slick when we were trying to fire the 357 rounds quickly. The plain black rear sight made acquiring the sight picture quickly more difficult than with the Python’s highlighted sights, we thought. Our testers were slower and less accurate during the double-action test with the 686, and speed and accuracy are all that matters in a situation that requires you to draw your weapon. We also noticed during this timed test that the trigger on the 686 was smooth and had a slightly beveled edge.

This caused our trigger finger to slip around a bit on the trigger, a noticeable difference from the defined ribs on the Python. The final issue that pushed the 686 down a notch was the grips getting in the way of ejecting the spent casings. The thicker wood grips on the 686 caught the casings closest to the frame when ejecting and would sometimes require us to hold the ejection pin with one hand while pulling them out with the other. That’s not an issue at a range, but it could be a costly problem in any other situation.

Our Team Said: The issues with the grips could be fixed as quickly as it takes to change them. So we feel that given the price and rarity of the Python, you can’t go wrong with a Very Good, Excellent, or Like New Model 686-2. Make a few inexpensive changes to fit your tastes, and you’ll have a lifelong companion for half or perhaps a third of what a Python will cost. That’s a lot of money these days.

Testing coordinated by Austin Miller, written and photographed by Gun Tests staff.