For whatever their reasons, some folks aren’t happy with the ballistics of a .22 LR and want just a bit more horsepower in their handgun.

Not wanting to reload, and rejecting the cost of the available loads for the little .32 revolvers, these good folks have the option of the .22 Magnum. One of the more useful barrel lengths on a small revolver is 4 inches, and while you’re at it you might want adjustable sights on the handgun. A 4-inch adjustable-sighted .22 Magnum is getting pretty near the ideal trail gun; all that’s left is to make it of stainless steel, and we’ve arrived.

Before we get into our test session, let’s consider how we might use this .22 Magnum revolver. Yes, it’ll do for self-defense in spite of there being many better first choices, so we ought to figure on finding out how well and how easily it shoots double action. For that purpose, capacity might be important, too.

Of course we’ll bust some tin cans with it, perhaps even full pop cans to see the burst — and waste — of all the soda. This sort of informal target work requires a single-action trigger pull that will let us win bets at long range. Then, having busted the tin can at long range we’ll want to know how well the thing prints on paper targets, and then that good trigger and adjustable sights will come into their own, to center the groups and let us get the most out of the gun.

The gun, of course, must look good to impress our friends, and be manageable so that our lady friends — or men friends if the buyer is a lady — will be duly impressed and want to shoot it themselves. This mandates a classy appearance and good workmanship.

Finally, the cost of .22 Magnum ammunition being higher than that of regular .22 LR (Long Rifle) ammo, the price of this piece ought not to break the bank. However, we don’t want to put good money into a turkey, and a bit more money might buy us lots more gun. Sounds like we better let Gun Tests sort us out a good handgun.

Back in February 1998, we wrung out a trio of kit or trail guns very similar to the Magnum versions tested here, but in .22 LR. We noted the limitations of the cartridge as to potential targets. The biggest for the .22 LR ought to be, we considered, about the size of a raccoon. With the added power of the .22 Magnum, that size goes up. Some seasoned shooters have used this caliber handgun to take treed cougars, but that’s probably a stretch. However, the .22 Magnum does have significantly more power than the .22 LR.

The Guns

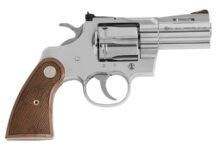

We chose the Smith & Wesson Model 651, the Rossi Model 515 and the Taurus Model 941. All our test guns were stainless steel revolvers with 4-inch barrels and adjustable sights. All had black finger-groove rubber grips, but Rossi provided a second set made of wood. Here’s the rundown.

The Smith & Wesson (S&W) Model 651 set the standard configuration, the others in this test being copies of it. This little revolver used to be called the Magnum Kit Gun, but is no longer listed that way. The gun was reinstated into the S&W line in 1991 as a limited edition offering, but has since become a standard item.

[PDFCAP(1)].Our Smith had a uniform matte stainless finish overall with a frosted upper surface to the frame. The hammer and trigger were color case-hardened. The revolver had rubber grips (Uncle Mike’s Combat grip to be exact) that fit well enough and looked good. Our test gun had a rounded butt covered by the rubber grips. The bases of the six chambers were countersunk into the cylinder, so the cartridges were essentially surrounded by steel. This possibly kept out some dirt, definitely looked great, but most surely cost more to do than if the cartridge bases simply bottomed against the rear of the cylinder.

Next up, the Rossi Model 515 was a superficial clone of the S&W, but it didn’t quite catch the neat lines of the Smith. Our test gun had two sets of grips with it. One set was of Brazilian hardwood with pressed checkering in a basket-weave pattern. These grips didn’t cover the backstrap. The other set of black rubber grips wrapped around the backstrap. These had finger grooves and molded checkering. The stainless metal finish was unevenly brushed on both frame and cylinder. The top of the frame was frosted. Rossi achieved concealing the rims of the cartridges in their six-shot cylinder by simply relieving the rear of the cylinder, leaving an outer rim that hides the brass.

[PDFCAP(2)].The Taurus Model 941 had a brightly polished stainless finish. It also had a full-length underlug that shrouded the ejector rod. The rubber grips encircled the entire grip strap and, in addition to the finger grooves, had molded, raised bumps on the sides to aid grasping. The Taurus held eight shots, and the cylinder was relieved at the rear, similar to that on the Rossi, to hide the cartridge case heads.

[PDFCAP(3)].Sights

The Smith & Wesson 651’s front sight had a bright orange plastic insert in its stainless blade, the blade being integral with the barrel. The rear sight was the usual click-adjustable target sight with a flat black finish. It provided a good sight picture.

The Rossi 515’s front sight had a red-orange plastic insert that was similar to that of the Smith & Wesson, but it was set into a blue/black blade that was pinned to the barrel ramp. The click-adjustable rear sight featured a stainless base and a black blade with a white outline around the notch. This gave the best sight picture of the test, being both clear and easy to acquire. Also, the adjustment screws were large, which our shooters though was a good feature.

The Taurus 941 featured a pale orange plastic insert (do we see a trend here?) in the integral front blade, and this revolver had an all-black rear with a white-outlined notch. The adjustment screws were very small. The windage adjustments were via opposing screws, a very crude system. We thought the sights were easy to acquire, but provided an ill-defined and somewhat fuzzy sight picture.

We wonder if anyone has tried a brass or “gold” metallic front sight insert that can be blackened with a match or candle, which would melt a plastic insert.

Controls

The Smith & Wesson’s ejector rod was not shrouded, but the front end was supported by a spring catch that formed the front-end lockup for the swing-out cylinder. This gun had the new-style S&W release catch for the cylinder. This was slightly smaller than what S&W used to provide, but worked in the same manner: Push it forward to release the cylinder. It worked smoothly, and was less obtrusive than the releases on the other two revolvers in this test.

The Rossi had a shrouded ejector and what looked like an exact clone of the old S&W cylinder release. This worked in the same manner as that of the Smith, press it forward to release the cylinder. It worked smoothly, and had good slip-resistant checkering.

Taurus put essentially the same style cylinder release on their revolver as did Rossi, big like the old S&W control. However, the checkering wasn’t done well enough to prevent the thumb from slipping, and fumbling when opening the cylinder.

Fit and Finish

The Smith & Wesson 651 had no sharp edges and the sideplate was very closely fitted. Moving parts had little or no play. The gun indexed properly on all chambers. We measured the barrel-to-cylinder gap at a somewhat loose 0.009 inch. We also measured headspace from the rear of a chambered and unfired Winchester cartridge to the recoil shield on all three guns. That of the S&W measured 0.006 inch, which was good. Our testers judged the overall fit and finish of the S&W to be very good.

The Rossi 515 had a few deep tool marks on its recoil shield. The edges of the cylinder crane and top strap were quite sharp. We also found tool marks in the bolt stop notches, and as already noted, the finish over the whole gun was somewhat uneven. Both sets of grips fit reasonably well, and the fitting of the sideplate was acceptable, despite a few very minor gaps. Moving parts had a small to moderate amount of play. The indexing was fine on all chambers. The barrel-to-cylinder gap was 0.008 inch. Headspace measured 0.002 inch, much too little for easy functioning.

On the Taurus 941, we found tool marks on the recoil shield. The edges of the cylinder crane were sharp. We also found some rub marks on the left side of the hammer and on both sides of the trigger after 100 rounds. We thought the cylinder had a lot of play in all directions. The chambers were very tight, too much so for easy loading. This also caused extraction problems. The other moving parts had moderate play. The sideplate was well fitted, though. The gun indexed well on all chambers. The barrel-to-cylinder gap was 0.005 inch. The headspace checked out at 0.010 inch, which was too much.

Triggers

Our test Smith & Wesson 651 had a 13-pound double-action trigger pull that we thought was about a pound too heavy, although smooth. The single-action pull was very good at 3-1/4 pounds. Both pulls had a small amount of overtravel. The trigger itself had an ungrooved 5/16-inch-wide face. The trigger reach on this gun measured 3-1/8 inches, and we thought it lent itself to those with small hands.

Our Rossi 515 had a double-action pull of 14 pounds that was reasonably smooth, but about 2 pounds too heavy. The single-action pull measured 4-1/4 pounds, and was okay, we thought, but could have been a pound lighter. Both pulls had moderate overtravel. This revolver’s trigger was ungrooved and 5/16-inch wide. When the rubber grips were installed, the length of reach was 3/8-inch longer than when the wood grips were installed. With the rubber grips, it measured 3-3/8 inches.

The Taurus 941’s trigger was also 5/16-inch wide with an ungrooved face. It had a 15-pound double-action pull, smooth but at least 3 pounds too heavy. The single-action pull was 3 pounds, which we liked, but it might be a bit too light for inexperienced shooters. Both pulls had minor overtravel. The reach on this handgun measured 3-1/8 inches which, like the Smith, was a good size for shooters with small hands.

All three revolvers had internal passive safeties, which prevented firing when the trigger was not pulled all the way to the rear. They all worked properly.

Handling and Shooting

We test fired the .22 Magnum revolvers with Winchester Super-X 40-grain JHP, CCI Maxi-Mag 40-grain JHP, and Federal Classic 50-grain JHP ammunition.

The Smith & Wesson was the lightest gun of this test, weighing 26 ounces. We thought it was the most evenly balanced. Pointing and target acquisition were the quickest and the most natural of all three guns. One problem was the extreme curvature of the grip’s backstrap, which didn’t fill the bottom of the shooting hand, but its overall shape and finger grooves (Ugh! Some of us don’t like to be told where to place our fingers.) were the most comfortable. The S&W extracted stiffly with the Winchester ammunition, but was free and easy with the other brands we tried. There were no other problems. The best five-shot groups at 15 yards were produced with Winchester’s Super-X ammunition at just under 1.5 inches average.

The Rossi was the heaviest gun, at 30 ounces. It was a little more muzzle heavy than the Taurus 941, so target acquisition was the slowest. It pointed low for us. The blocky shape of the rubber grip made the gun hand-filling, though not particularly comfortable. Our test shooters with medium-to-big hands thought the finger grooves were a little too small. Remember we told you the headspace was only 0.002 inch, and that’s not enough. We found that cylinder rotation was prevented numerous times by fired cases. Also, the unfired Winchester ammunition sometimes stopped it from turning. The cylinder hung up numerous times even with the Federal and CCI loads. Extraction was smooth with all ammunition, so the problem was not sticky chambers and rounds not going all the way home. It was the insufficient headspace. Sad to say, the accuracy didn’t measure up. Our best five-shot average groups, 2.3 inches at 15 yards, were produced with CCI Maxi-Mags. Contrast that with the worst group from the Smith & Wesson at 1.8 inches and you’ll see where we’re heading.

The Taurus weighed an ounce less than the Rossi at 29 ounces. As already noted, it had eight tight chambers. We had to push the unfired rounds into the chambers to seat them, and sometimes that wasn’t enough to ensure free rotation of the cylinder. This also caused us problems when removing the fired cases to the extent that extraction was extremely hard with the Winchester and Federal loads. The CCI load fared better, but was still a little stiff coming out. The best 15-yard groups we fired with the Taurus were about 2.6 inches average, with the CCI ammunition. The worst were produced with Federal’s Classic ammunition at 3.1 inches average.

[PDFCAP(4)].Our Picks

Remember our criteria at the beginning of this article, as to what uses we might put this type of handgun? For self-defense, we wanted reliability first and capacity second. Neither the Rossi nor the Taurus would reliably rotate their cylinders, so in spite of the 8-shot capacity of one of the Brazilian-made revolvers, the Smith & Wesson gets the nod for self-defense use. However, that’s not the whole story.

Next up, can you hit the pop can at long range? Better have the Smith & Wesson in your hand when you try, for its largest average group (1.8 inches) was smaller than the best group of either of the other two (2.3 inches). The 3-pound single-action trigger pull of the Taurus might help you get all it has to offer, but the S&W’s pull was only half-pound heavier and its accuracy was about 3/4-inch better at only 15 yards. So, we’d bet on the shooter with the S&W. To hedge that bet, remember the Rossi was the most muzzle heavy, and that would help an offhand shooter, though he’d have to fight the 4-1/4-pound single-action trigger and an inherent accuracy disadvantage as well.

To impress our friends with the looks of the gun and make them want to shoot it, the high shine of the Taurus might catch the eye first. The finish problems with the Rossi wouldn’t, but it does have a business-like look due to its blocky grip, plus the option of real wood grips or rubber, with distinctly different trigger reaches to help fit individual hands. The Smith & Wesson bespeaks class, though, and we thought it was the best-looking gun of the bunch.

However, the cost of the Smith & Wesson was the highest, at $468. That doesn’t leave much money to buy ammunition. The Rossi was the least costly at $270, and we like the idea of saving $200 over the S&W a lot. The Taurus set us back $384, and with its many problems in loading, shooting and unloading, we’d think twice and maybe three times before we’d buy this one.

Comparing the Rossi and the Smith & Wesson more specifically, the problems with the Rossi stemmed, we thought, from insufficient headspace. That can be cured. If it were too large, it could not easily be cured, if at all. All three revolvers had their ammunition preferences, and careful selection and perhaps a bit of slicking-up work could make the Rossi entirely reliable, if not as accurate as the S&W, and it might then be thoroughly satisfactory. For pride of ownership, plan to spend the money on the Smith. That’s what we would do.