When the .308 or .30-06 isn’t enough, most gunnies turn to the .300 Winchester Magnum, and that’s probably a mistake. While the .300 Winchester Mag is a step above the ballistics of the .30-06, it’s not a huge step. There’s not a lot of practical difference between the two, at least not enough to be more than a few minutes’ discussion among knowledgeable riflemen. We’re talking 200 fps difference with 180-grain bullets. This makes very little difference in trajectory, though it would make somewhat of a difference in bullet performance at long range.

Rifle power may be succinctly defined by the velocity at which a cartridge can propel a given weight of bullet, and that’s a simple and universal way to compare cartridges. One quickly gets used to thinking in terms of “180 grains at 2,700 fps,” instead of lingering over indefinite but catchy cartridge names. If you factor in bore size, you can get a quick mental picture of the performance of any given cartridge. Also, you can quickly get a handle on any new offerings by the manufacturers, and can estimate their performance from the speed at which they drive their chosen bullet weight.

For example, if we are talking about .30-caliber cartridges that propel 180-grain bullets at 2,700 fps, we’re discussing the .30-06, or something very similar. If someone mentions 180 grains at around 2,900, you know they’re talking about the .300 Winchester, or something very similar.

[PDFCAP(1)].The only gains from increased speed, for a given bullet, are flatter trajectory and the ability of the bullet to open at increased range because of the higher retained directional and rotational velocities. To put it another way, if your cartridge/bullet combo performs adequately for you at average hunting ranges, increasing the velocity a little bit won’t make the bullet kill a lot better.

Yet bigger is always better, or so we’re told. There will always be a market for the most of anything, be it bullet velocity or money spent on a rifle. Although the .30-06 has worked well on all big game for nearly a century, the .300 Winchester Magnum has been extremely popular as a second rifle for those who already had an .30-06. Still, the increased velocity is not a lot, and if we had an .30-06 we would not bother with a .300 Magnum, and vice versa.

However, what if we drive that 180-grain bullet at 3,300 fps? Wow! Now we’re talking HOT .30s. That’s 500 fps faster than a normal .30-06 load, which is a big jump in performance. Are there any cartridges that achieve that? How about the .300 Weatherby? Don’t forget the .300 Dakota. Anything else? Yes, the new Remington .300 Ultra Mag will do that, or at least Remington says so. We decided to find out what you get with this kind of performance, and what, if anything, you give up. Are the rifles too heavy? Do they kick too much? Are they too loud, or inaccurate? Let’s see.

The Rifles

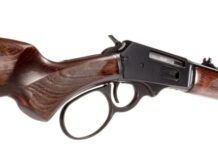

We gathered a trio of rifles to see what you, the consumer, can expect from one of the super-hot, essentially proprietary, thirties. That means, if you want their rifle and ammo, you’ve got to buy it from the manufacturer. (Other makers load ammo for the .300 Weatherby Magnum.). We chose the $4,395 Dakota Model 76 Classic Sporter in .300 Dakota, the $600 Remington Model 700 BDL Custom Deluxe (with Enhanced Engraving) in the new Remington .300 Ultra Mag chambering, and the $949 Weatherby Mark V Sporter in .300 Weatherby.

All of our rifles had wood stocks, none more lovely than the Dakota’s. All had 26-inch barrels, to make the most of their increased chamber capacities. The Remington and Weatherby had cheekpieces and Monte Carlo-style stocks while the Dakota was, per its description, classic shaped. The Remington had iron sights fitted, while the other two had neither iron sights nor holes to mount them.

The Dakota came with a fine, extra-cost, 3.5-14x Leupold scope mounted in Talley rings. The rifle was fully sighted-in with ammunition that was custom loaded for that specific rifle. You can’t get more proprietary than that. We installed the (Czechoslovakian) 3-9x Artemis scope onto the Remington and Weatherby in turn, and proceeded with our evaluation.

Dakota Classic Sporter Model 76 .300 Dakota

Our recommendation: Buy it. This was one fantastic rifle, very accurate, reliable, smooth, gorgeous, and well worth every penny of its cost, in our opinion. If you want one of the best bolt-action sporters in the world, one built right here in the U.S., buy a Dakota.

Total beauty, superb wood and first-class metal work delight the eye that beholds this gun. We feel this rifle exemplifies how a bolt-action rifle ought to look. That was our first impression of the $4,395 (not including scope) Dakota Sporter, and it proved to be entirely accurate.

The base price of the Dakota Sporter is $3,195. This one had upgraded wood, Talley bases and rings, and a skeleton-type grip cap. These brought the price up an additional $1,000 or so, and only you the purchaser can decide if they’re worth it. One spends a great deal more time looking at a rifle than shooting it, so it makes sense for it to be attractive. Talley rings and bases are among the very finest in the industry, and if you’re spending serious money for a special rifle, it makes little sense to put anything but the best onto it. The grip cap, we felt, added significantly to the overall look of the rifle.

Built around Dakota’s proprietary action that closely copies the pre-’64 Winchester Model 70, this rifle had controlled feed and positive ejection, both features handed down from early Mauser designs. The Dakota was essentially a finely built custom-made rifle that anyone would be proud to own.

Dakota’s upgraded wood was California English walnut of a golden-honey color with black streaks and swirls that delighted the eye. It had perfect grain through the grip and into the forend. Such wood has never been cheap. The wood was perfectly filled, and the hand-cut checkering was extremely well done in a pattern that blended with the contours of the stock. The oil-type finish brought out all the wood had to offer, which was plenty. No extraneous forend tip marred the front of the stock. A tasteful soft black pad marked with the Dakota name covered the butt. The stock shape was muted, had no cheekpiece or Monte Carlo, and didn’t need either.

The pistol grip was capped with a skeleton ring of steel, with perfectly checkered wood within the enclosed area. The forend shape was oval, deeper than it was wide, which we found extremely comfortable. Perfectly executed borderless checkering came down deep on both sides of the forend and through the pistol grip area. The stock finish on the checkering exactly matched that on the surface of the stock, which was not the case with either of the other two rifles in this test.

The flat area on the bottom of the stock around the all-steel floorplate and trigger guard blended forward nicely into slightly flattened areas, and thence into the well-rounded forend. The rear line of the pistol-grip checkering flowed upward in an S-shape to run gently into the rear edge of the action. The opening in the wood at the ejection port ran precisely into the lines of the front and rear receiver rings. The finish in the stock cutout underneath the bolt handle was exactly the same as that on the visible surfaces of the stock. The inletting around the top tang of the action, which was shaped much like pre-war Winchester Model 70 tangs, was perfection. To get precise wood-to-metal fit on a clover-leaf shaped tang takes lots of time and effort.

Stock details like these have to be done exactly right or they cheapen the appearance of the gun. When done correctly, they add immensely to the appearance and tastefulness of the rifle, and Dakota did a superb job.

We wonder if we really have to bother telling you that the barrel on this beauty was not free-floated. It was bedded full-length. Old-timers will tell you this is not a compromise. It used to be the only way to get the most out of a rifle, but it has to be done extremely well, with very stable wood, to get the rifle to shoot consistently well. That was the case with the Dakota Sporter.

The matte-blued barrel tapered quickly down to slim dimensions soon after it left the receiver. The barrel measured 0.56-inch diameter at the muzzle. This gave the rifle exceptionally good balance. The point of static balance was in line with the rear edge of the front action ring. This rifle felt lively, yet not muzzle-light.

The Model 76 Classic Sporter was fitted with QD sling-swivel studs at forend and buttstock, but there was no sling. The bolt may be removed from the rifle by lifting a nearly invisible latch at the left rear of the action. The rearmost end of this was checkered to ease lifting it. The bolt body was polished white, but the rest of this all-steel rifle was beautifully matte blued in a manner that resembled rust bluing, but wasn’t. No iron sights marred the smooth barrel surface, and we felt they would have been out of place. The floorplate opened easily by depressing a button in the upper front edge of the trigger guard. The rounds could also be removed by cycling the bolt with the three-position swinging safety in its middle position. The trigger pull was a dream. It broke at 3 pounds, with zero creep and zero overtravel. Feed, function and ejection were all flawless.

Shooting the Dakota was another pleasant surprise. The first three rounds cooked over our chronograph at an average of 3,300 fps, for 180-grain bullets. The Dakota delivered the goods per their advertising, and didn’t hurt us in the bargain. Unlike the muzzle-braked, 15.4-pound Dakota Longbow we tested last month, the bang from the cartridge was directed downrange and didn’t hurt our ears. At 9.2 pounds, the Dakota Model 76 Classic Sporter had minimal kick, thanks to a good stock design and a good buttpad.

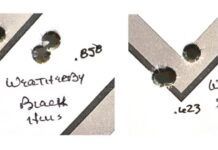

The spindly 26-inch barrel looked like it would heat excessively, and we thought that might degrade performance if the barrel had any internal flaws. We didn’t try long strings of rapid-fire with the Dakota, but all our shooting led us to believe the skinny barrel wasn’t a problem. The average of all groups was less than an inch, testament to the overall high quality of the package.

The rifle came with a $1,570 Leupold 3.5-14x LPS scope with 30mm tube. Although the scope looked huge, we found it to be ideal for the rifle.

We conclude the Dakota section of our report with a little story. We know of a fellow who buys very ordinary rifles, then spends dozens of hours on each of them adjusting trigger pulls, testing various scopes to find just the right one, reloads incessantly to find the best load, and sometimes refinishes them to enhance their plain wood. He often has to take the rifles to gunsmiths because they have bedding problems, or they don’t feed perfectly. This fellow’s time is actually worth $50 an hour, so he spends thousands of dollars of his time on $500 rifles to turn them into $550 rifles. It’s a hobby that doesn’t make a lot of sense to us.

With the Dakota Sporter, all that development work has been done. This rifle needs nothing. It’s complete, all ready to go. More important, because it is a fine rifle it will appreciate in value at a higher rate than the ordinary rifle. A $500 rifle will be worth about $500 in a decade, but fine rifles like the Dakota have historically increased greatly in value with time. That’s why the price of such a thing is more than justified, and that doesn’t even include the great joy of owning and shooting it along the way.

Weatherby Mark V Sporter .300 Weatherby

Our recommendation: Buy it. Its accuracy was the best of the lot, but we thought a few of the details could have been done better, but in all it was a sound rifle. Our first impression of the Mark V was obtained the same day as our first impression of the Remington 700 BDL in .300 Ultra Mag. It was that the $600 Remington was a better-looking rifle than the $949 Weatherby.

This impression was obtained from a long glance at each of them standing side by side in the harsh light of day. The proof of how well they worked and shot remained to be seen. However, the sparse checkering of the Weatherby Mark V, the clumsy feel of the stock forend, the mediocre figure of the wood, and some marring of the blued finish on the barrel would require some pretty doggoned good shooting and handling qualities to offset its higher cost.

Oddly, there was no manual or other paperwork in the box. The rifle had no iron sights, nor were there rings in the package. We bought a set of Weaver bases and installed a 3-9x Artemis scope.

The 26-inch barrel was quite slender, tapering quite rapidly but smoothly from an inch in front of the action. Its diameter at the bore was 0.6 inch, and the stock was cast off about a quarter inch. The weight of the rifle was mostly between the hands, and this, together with the cast off, gave the rifle a lively feel that belied its weight of 7.9 pounds without scope. The scope brought the test weight up to 9.2 pounds. The trigger pull was crisp and clean, breaking at 41/4 pounds. The overtravel was taken up by what felt like a heavy spring, and we liked that.

Weatherby put a trestle-style rubber buttpad onto the rifle, and while you may not like the look of such a pad, this one did a good job of reducing felt recoil. There was no white line spacer. The higher-grade Deluxe version of the Mark V Weatherby has this feature here and on its contrasting grip cap and forend tip, if you want it.

The stock had a glossy epoxy finish that we felt tended to obscure some of the figure in the wood. However, it was very hard and resistant to scratching, and we feel it will keep the Mark V looking good for many long years. The hand-cut checkering was sparse and not perfectly even, though it performed its function well. The forend had a flat-bottom configuration that, when combined with the marque’s pronounced Monte Carlo cheekpiece, lets the rifleman know he’s got a Weatherby Mark V in his hands even if his eyes are closed. Not everyone likes this feel.

This Weatherby had an aluminum-alloy trigger guard and floorplate. The trigger guard had a stylized “W” on the bottom, filled with gold paint. The guard incorporated a floorplate release that worked very well. The bolt had Weatherby’s trademark nine locking lugs, and it required only a 60-degree turn to open or close it. Opening it quickly required a fast jab upward. Bolt operation was very smooth and slick. To remove or replace the bolt, the trigger must be held rearward. Extraction was by an external claw about a quarter-inch wide, and ejection by a captive plunger within the bolt, similar to that of the Remington. It all worked very well.

Weatherby continues to use the old 1917 Enfield-style safety, which consists of a lever protruding from the right rear of the bolt sleeve. To put it on, rotate it rearward until it is nearly horizontal. Slipping it forward (off) was both easy and natural. It worked properly. With the safety on, the bolt cannot be opened. Therefore the magazine must be emptied out the bottom, which we found to be easy. Weatherby rifles have been made in the U.S., then in Germany, and then in Japan. The current version of the Mark V has “Made in U.S.A.” stamped onto the left rear of the receiver. The receiver was buffed after the impression of the serial number, maker’s name, model name and the relevant patents. This gave the action a slight look of having been refinished. Unfortunately, the caliber designation on the left rear of the barrel was stamped unevenly into the steel and not buffed over, which gave those letters an uneven raised appearance. The discrepancy between markings served to increase the “refinished” look of the action.

The matte bluing, however, was very evenly applied to barrel, action, bolt sleeve and handle, and these parts all matched the finish of the trigger guard and floorplate. The outside of the massive bolt body was polished a matte white (no finish), but the nine longitudinal grooves held bluing. This treatment hid the normal scratches the bolt got from its motion within the action, and kept the bolt looking good throughout testing.

The barrel was free-floated from the action forward to about 3 inches from the front of the forend. Then it contacted the forend for 2 inches, then was free-floated for the last inch. This bedding technique is designed to put upward pressure onto the barrel, which can help accuracy. The gap between barrel and forend on this Weatherby was minimal, and not at all obvious. The inletting throughout the rifle was very good.

On the range, we found the 180-grain “Authentic Weatherby Ammunition” lived up to its reputation, delivering 3,265 fps with the 180-grain “PT-EX” bullet. The ammunition, by the way, is made in Sweden. The rifle was comfortable to shoot, and everything worked correctly. Feeding, function and ejection were perfect. Operation was distinctly smoother than that of the Remington. Closing the bolt required just a smooth push forward and a slight effort downward. Opening it after the shot required a sharp bump upward.

The rifle delivered truly outstanding accuracy. To keep things even among the rifles, we used only Weatherby’s 180-grain load, but factory-loaded Weatherby ammunition is available with bullets from 100 up to 220 grains. Also, other companies besides Weatherby make ammunition for it, a distinct advantage over the other two calibers tested here.

Although rifles chambered for Weatherby ammunition are now made by companies other than Weatherby, many riflemen feel that if you want a real Weatherby with all the bells and whistles, it ought to be made by that company. Undoubtedly you’d have an easier time finding ammunition for the Weatherby than the other two, especially the Dakota.

700 BDL Custom Deluxe Remington .300 Ultra Mag

Our recommendation: Buy it. This rifle, at the low-end of the scale, performed as good as it looked, with acceptable, if not outstanding accuracy. This $600 rifle is a real looker, with its pseudo-engraved action and floorplate, wrap-around forend checkering, and clean lines.

Remington’s website compares their new .300 Ultra with the .300 Weatherby, but uses a lower velocity for the Weatherby than we measured. We think the .300 Ultra Mag will sell well to those who want a lot more performance than the .30-06 without going to a larger bore diameter.

Dakota was, we believe, the first company to utilize the .404 Jeffery case as the basis for a line of proprietary unbelted magnums, one of them the hot .300 Dakota tested here. The fact that it was a good idea is evident from Remington’s use of the same Jeffery case for their .300 Ultra Mag. The .404 Jeffery case has a base diameter essentially equal to the outside of the belt on belted magnum cases. This means that for a given length, a Jeffery-based case holds more powder than a belted case.

More than providing extra power, the Jeffery-type case feeds more smoothly because there’s no belt to get in the way. Headspace is achieved on the case shoulder, just as with a .30-06 or .308. There is really no reason not to use big cases without belts, as John Rigby knew back at the turn of the century when he brought out his .416 Rigby. We wonder why it took so long for a major U.S. company to follow suit.

The 700 BDL Custom Deluxe Remington had nothing new for diligent readers of Gun Tests. Basic features of our test rifle included a recessed-head bolt with Remington’s little extractor, bolt-plunger ejector, slick bolt movement, and a trigger pull that broke at 43/4 pounds. Remington puts a large trigger guard on their rifles, which we like. It gives room for fat fingers or for gloved use, but if you wear gloves to shoot your rifle, be extremely careful. You might not feel the trigger, and get an unwanted shot.

The stock had excellent cut checkering in a multi-point, skip-line pattern. It looked good and worked well. The black rubber buttpad was offset with a white-line spacer, as were the pistol grip cap and the black forend tip. Two sling swivel studs were fitted. We’ve come to like Remington’s “engraving.” If it can be achieved as inexpensively as Remington does it, why not have it on the rifle? As the finish wears, the rifle looks better. A rifle without engraving can look pretty bad as it ages.

The glossy stock finish was evenly applied over the rather plain wood. The forend was free-floated from the action to near the tip, then made contact with the barrel. The contrasting forend tip was entirely free-floated. The wood contacted the right side of the barrel at about the location of the rear sight, and we wondered how this would affect accuracy.

The metalwork was evenly polished and matte blued, and nicely complimented the rifle. The floorplate and trigger guard were of aluminum. On a rifle of this power the added weight of steel parts here would have been welcome, but not entirely necessary. The rifle weighed 7.7 pounds without scope. Our test weight, with 3-9x Artemis, was 9 pounds even.

A bit of initial stickiness in lifting the bolt handle went away as we used the rifle. The iron sights were a U-notch rear and a post/bead front, with hood. We’ve said it before, but the rear notch leaves lots of doubt where to position the front bead for elevation. The rear sight was adjustable for windage and elevation. The safety lay on the right rear of the action, and permitted the rifle to be unloaded by using the bolt. This is done by putting the safety fully on (rearward), and then pressing each round forward until it popped up out of the magazine, whereupon the round could be removed with the fingers. The magazine, like all three rifles here, held three rounds.

At the range, the Remington .300 Ultra Mag proved a bit cranky to feed from magazine to chamber, but we expect this will smooth out with use. There was significant drag from the magazine rails, but the cases went straight into the chamber. We discovered a bit of creep in the trigger we hadn’t detected at our desk. The biggest surprise was that the Remington kicked noticeably harder than either of the other two rifles tested. However, let it be said that none of these rifles is for the recoil-shy.

We thought we had a superior rifle after the first three-shot group went downrange, for the Remington put the 180-grain Nosler Partition bullets into a group that measured 1 inch. Unfortunately, we were unable to approach that again. Our overall average was 1.6 inches. After our recent experience with the incredibly accurate precision or “tactical” rifles, we kept the bores on these three pretty clean, so fouling wasn’t a problem. It’s just that the Remington was a 1.6-inch rifle, and that’s not all bad. We feel that is acceptable accuracy, just not as good as either of the other two. Remember we told you the forend touched the barrel near the rear sight, where it ought to have been clear? That is where we’d look first if we owned this one.

Gun Tests Recommends

One simple head-to-head test illustrates how easy it is to gauge the complex functioning of a bolt-action rifle. We shot a round and worked the bolt as fast as we could to get the next round into the chamber, though we didn’t fire the second shot. The effort required with the Remington was significant, and it wasn’t all that fast or smooth. The handling effort with the Weatherby was much less, though the short-throw bolt lift required a knack. Feed and feel were very good, and the Weatherby was noticeably smoother and faster than the Remington. Then came the Dakota.

We worked the Model 76’s bolt as fast as we could after the first shot, and it was like handling a knife in butter. The empty went flying, the next round went into the chamber like a lawyer after a dollar, and it felt so smooth we actually fired the second shot. Felt recoil was insignificant with this rifle, way less than the other two rifles, and we fired the two shots and got two good hits inside of two seconds. The bottom line is that you get what you pay for.

Dakota Classic Sporter Model 76 .300 Dakota, $4,395. Buy it. There were no compromises anywhere on this rifle, and you simply have to pay for this level of work.

Weatherby Mark V Sporter .300 Weatherby, $949. Buy it. This rifle was the most accurate of the three tested. And because of its history, other companies besides Weatherby make ammunition for it. Ammo for this gun will be easier to find, giving it an advantage over the other two.

Remington 700 BDL Custom Deluxe .300 Ultra Mag, $600. Buy it. It’s a new concept, a brave move for Remington, and for that we applaud them. The .300 Ultra Mag did give a velocity of 3,300 fps with 180-grain bullets, and this gives the buyer lots of performance for a whole lot less money than the Weatherby or Dakota.

I made something out of the 300 Win Mag to alibi Remmie’s sloppy 700’s chambers. I use 300 Wea. brass, necked down to 300 Win Mag. With longer neck. I trim this to +0.050” and had GS deepen neck throat in my M 700 rifle the same amount. This has a unique advantage in that resized case will have at least 0.304” long neck, and usually 0.314” necks. This doubles 300 UM’s full caliber neck length, and is the largest case which Hogdgon publishes reduced loads for H 4895. So I get reduced loads and a better neck grip on reloaded cartridges.