By the early 1980s there were two commercially successful semiautomatic shotguns being produced for the American market: the Browning Auto-5 and the Remington Model 1100. The long-recoil Browning Auto-5 shotgun (which by now was being produced for Browning by B.C. Miroku of Japan) had its loyal following, but its aging early 20th century design and “legendary recoil” made it a poor choice for all-round use, especially in the increasingly popular clay-target sports. The Remington 1100’s light recoil sensation (due to its gas operation), balance, and stock dimensions made it the clear winner in the American semi-auto shotgun market. A trip to any trap or skeet range would convince any observer that this was the most popular semi-auto shotgun of its day.

As clay target sports and shotgun use in general became more popular, other manufacturers entered this expanding shotgun market. One notable entrant was Smith & Wesson, a handgun manufacturer from Springfield, Massachusetts. Its 1000 semiautomatic shotgun (built to company specifications by Howa Manufacturing of Japan) soon developed a loyal following of its own among American shotgun owners. It was an extremely well-designed and well-built shotgun, stocked in straight-grained American walnut with an excellent gloss finish, and it had cut checkering (a welcome change from Remington’s stamped design). Models that followed included a waterfowler with a Parkerized metal finish and dull oiled stock, the Super-Skeet model with a palm swell, wide rib, ported barrel and Tula skeet choke, and the Super 12 model with a system to vent excess gas pressure that made it capable of firing any and all 12-gauge loadings available.

Eventually however, Smith & Wesson dropped the Model 1000 from its line. For a few years Mossberg put its name on the Model 1000 and the Model 1000 Super in both 12 and 20 gauge, but Mossberg also stopped selling the model 1000. While this shotgun was being imported, thousands of them were sold to American shotgunners. The gunsmith who services semiautomatic shotguns would do well to familiarize himself with this highly-regarded shotgun model.

Photo courtesy of American Gunsmith

Starting Work

Like other semi-auto, the Model 1000 is sensitive to dirt and powder residue. Careful disassembly, cleaning, and light oiling of its moving parts will cure many of its problems.

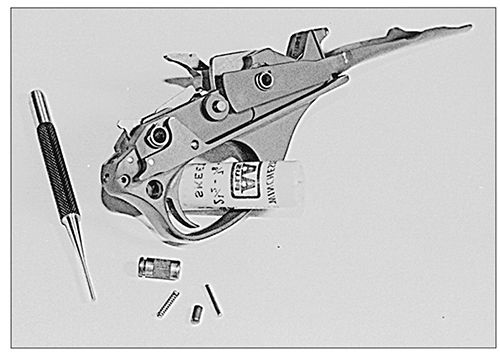

Disassembling this shotgun is very simple. Once you have determined that the shotgun is not loaded, close the bolt and with the gun cocked and the safety on, push out the two pins that retain the trigger assembly. The Model 1000 trigger assembly is more sensitive to foreign matter than most. This is especially true of target guns that use lower-pressure (often reloaded) ammunition. When cleaning this component it is important to not only wash it thoroughly with solvent and blow it clean with compressed air, but also to pay special attention to the safety and trigger.

Next, push out the pin that retains the safety spring and plunger with a 1/16-inch punch, being careful not to allow the compressed spring to fly out of the assembly. Remove the spring, plunger and safety button. This will allow you to clean not only the safety button but also the back of the trigger. When unburned gunpowder collects in these areas, the trigger will not have the full range of movement it needs to fully operate the trigger connector, and it will not fire. Clean this area thoroughly! There should be no further disassembly of the housing required.

The Model 1000 shotgun has a reversible safety, which you can easily alter to left-handed operation—simply reassemble the safety with the red side of the button on the right side of the shotgun.

Extremely good trigger pulls can be achieved from this shotgun by simply stoning its hammer sear to narrow the sear engagement. Be very careful to keep your stone perpendicular to the hammer while stoning. Do not stone this part excessively and do not change the angle of the sear. Since this shotgun‘s safety is no more than a trigger block, I recommend setting the trigger pull above 4 pounds on all field models. On trap or skeet model target shotguns, the trigger pull can be set to as little as 21/2 pounds. After any trigger pull adjustment, the trigger assembly should be tested to ensure that it will not fall off the sear accidentally. To do this, cock the hammer and put the safety on. Then with a nonmarring hammer, tap the trigger assembly sharply from every possible direction for several minutes. A target shotgun, of course, may be set up with an extremely light trigger pull, and may occasionally fail this test if it is hit very hard; but remember that a target shotgun is only loaded when it is pointed downrange. A field gun should never fire at any time during this trigger test!

Photo courtesy of American Gunsmith

Second Stage Disassembly

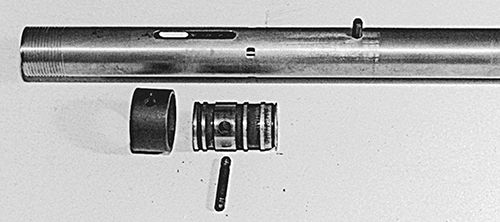

To disassemble the shotgun further, remove the barrel, forend and gas module and push out the pin connecting the piston (inside the magazine tube) to its connecting ring (outside the tube). Remove the connecting ring and piston and clean the piston thoroughly. Remove the bolt-operating handle, press the bolt-release button, and slide the bolt and action bar assembly forward and out of the receiver. Clean these parts carefully and inspect them for wear. Be sure to inspect the firing pin and its return spring by removing the bolt locking block.

The magazine tube can now be cleaned both inside and out. There is often a good deal of residue inside the magazine tube. You may want to hone this area lightly with a brake cylinder hone on a hand drill to thoroughly clean this surface.

Check the magazine tube for dents, tightness and alignment. A dented magazine tube might have been caused by owner abuse while removing or replacing the capacity reducing pin (duck plug). Be sure that movement of the piston is unrestricted. Poor alignment of the magazine tube will result in not enough gas passing from barrel to piston, and poor functioning at best. With the receiver in a bench vise, grab the magazine tube with both hands and see if you can loosen it. If it is loose or can be easily loosened, correct its alignment by putting the barrel back on the receiver assembly and checking to ensure that the gas ports in the barrel line up correctly with the gas holes on the top of the magazine tube. Once the holes line up correctly, apply Loctite and tighten the magazine tube nut. Look down the magazine tube from the front to be sure that the piston shock absorber is in position and in good shape. Many of these shock absorbers are damaged by solvents and excessive shock.

If you are dealing with a Super 12 or Super 20 model, the excessive shock is generally a result of a dirty gas-control module. To clean the gas-control module, place it in a vise and lightly compress the assembly until the pin can be easily pushed (not tapped) out. This can also be done with a C-clamp. Clean the gas module body, valve and guide thoroughly with cloth and solvent and reassemble. Do not oil the gas-control module.

Clean the receiver thoroughly and blow it dry with compressed air, paying special attention to the locking block recess at the top of the receiver. Be sure to clean this recess of all unburned powder. Scrape this area if necessary, using a sharpened piece of nylon rod. Check the nylon block in the back of the receiver for looseness or wear.

Photo courtesy of American Gunsmith

These blocks often become loose, and when they fall out of position they stop the bolt from coming rearward enough to recock the shotgun and extract a fired shell. If this nylon block is loose, remove it and clean it thoroughly. Inspect it to see if it is still serviceable. Clean the hole in the back of the receiver with solvent and glue the nylon block back in. I have used both AcraGlas (from Brownells) and Poly-Choke rib adhesive to make this repair. They both work well, but the Poly-Choke adhesive is better suited to absorbing shock.

The barrels of the Model 1000 shotgun are extremely well made; bore sizes are consistent and well polished and the fixed-choke models have extremely long chokes (very similar to the Browning Auto-5 fixed choke), which function very well. The later production screw-in choked models use either Win-Choke style extended tubes or flush fitting Invector tubes. Often the Model 1000’s choke performance can be improved by replacing the Invector style tubes with the longer (and more readily available) Rem-Choke tubes. This can be done by shortening the barrel about 1/8 inch and running right over the factory choke installation with Rem-Choke installation tooling.

Fixed-choke models can generally be retrofitted with Thin-Wall choke tubes, but because of their length, care must be taken to remove the entire factory fixed choke. The chamber forcing cone in the Model 1000 is very short, and your performance-seekers will no doubt want to lengthen it for lower felt recoil and less shot deformation. Because the outside of the barrel tapers very quickly in front of the chamber, I do not recommend making the forcing cone longer than 2 1/2 inches.

Replacement parts for the Smith & Wesson/Mossberg Model 1000 semiautomatic shotgun are readily available. They can be found at Gun Parts Corp., Smith & Wesson, and Lone Star.

Do you have a video available?

HEY ESTAFF,

Since 1983 I’ve been the owner of one of these beauties ! This article is fantastic and very helpful. I greatly appreciate it. I have taken my share of grouse, squirrel, rabbit and turkey with it. With a 18 1/2 ” barrel, it also makes a home defense weapon which will prove to secure you and your loved ones. It was one of the best deals out there in it’s time. Simple willingness to service this shotgun when needed is all it takes to keep it running. What a crime it was to discontinue such a shotgun. Mine is in 12 Ga, Modified, and is a dream to shoot !

Many thanks again,

Paul